NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Is 3D Technology the Key to Preserving Indigenous Cultures?

Smithsonian scientists apply 3D technology to indigenous artifacts to ensure native cultures survive and thrive for future generations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Killer_Whale_Hat.jpg)

The Smithsonian regularly works with several indigenous clans and communities to apply 3D digitization and replication technologies to cultural preservation and restoration issues. This past fall, as Tribal Liaison with the Repatriation Office at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, I continued this effort with the Tlingit tribe of southeastern Alaska.

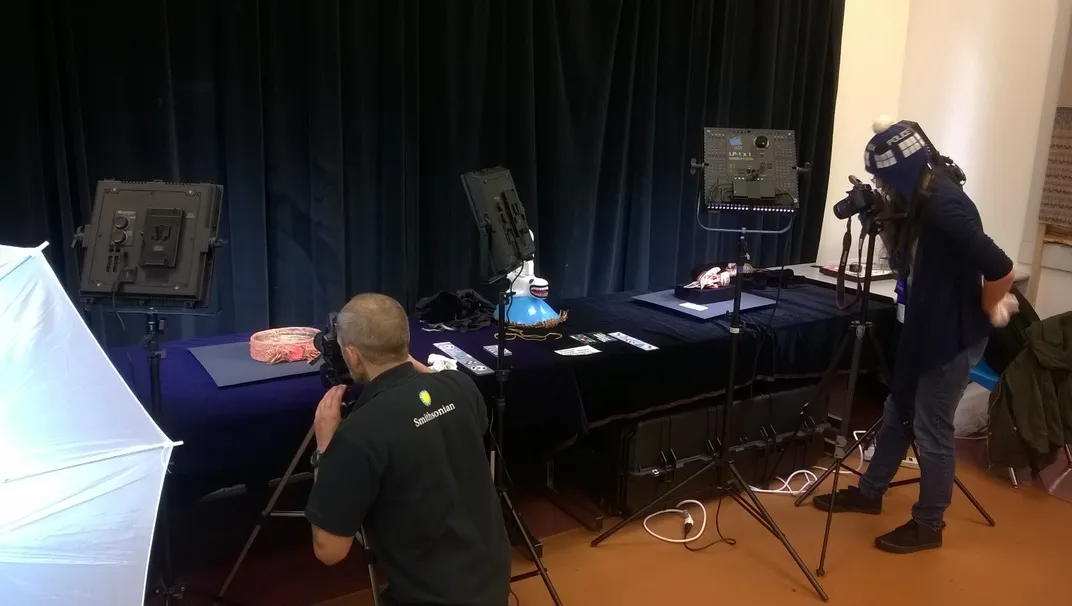

With equipment support from the Smithsonian’s Digitization Program Office and joined by University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill student and photogrammetry specialist Abigail Gancz, SIE Model Maker Chris Hollshwander, and Smithsonian Public Affairs Specialist Nick Partridge, I attended the 2017 Tlingit Sharing Our Knowledge Conference. Held at the Sitka Fine Arts Camp in October, the conference offered an ideal forum to further foster our relationship with the Tlingit people and present new opportunities for collaboration.

While at the conference, our team took over a room for four days and demonstrated 3D digitization and replication technology. Clan leaders brought in clan hats, helmets, headdresses and rattles to have them digitized using photogrammetry—a technique that merges data from hundreds of individual digital images--to construct 3D models. During the conference, the Tlingit received seven repatriated pieces, including several helmets and headdresses returned by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

At the request of the clans, we worked quickly to digitize these objects and archive the data as a form of insurance. Digital data from these scans can be used to restore or replace the hats if lost or damaged in the future, a key concern to clan elders as, in 1944, the Tlingit village of Hoonah burned and only two clan crests survived. After the fire, Tlingit carvers replaced several of the hats working from memory and perhaps a few old photos. Digital scans of such at.óow—clan crest objects—provide peace of mind that Tlingit artists could use the files or 3D technology to faithfully reproduce lost or damaged objects.

On previous trips to Sitka, the Smithsonian digitized two of the Tlingit’s most significant historical artifacts, a hammer and Raven war helmet, used by the Kiks ádi clan Chief K'alyaan in a battle with Russian forces in 1804.

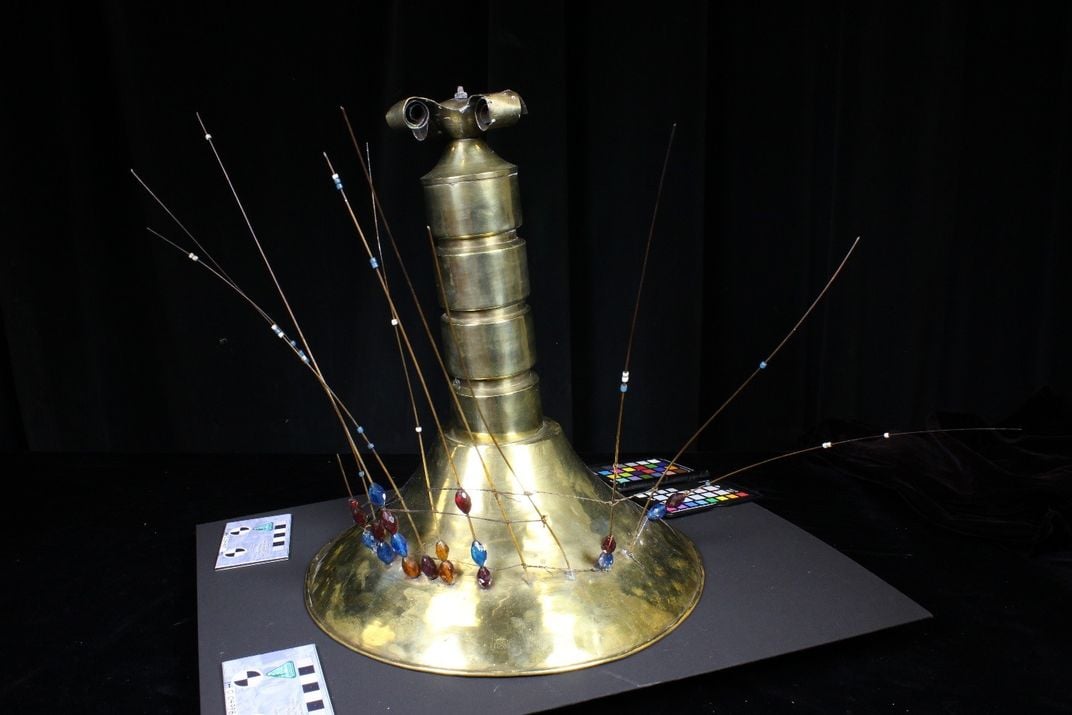

In addition, we were honored to be able to scan another significant piece of history, the Peace Hat. The Russian American Company made the Tlingit-shaped all brass hat and presented it to the Kiks ádi 213 years ago to cement peace between the Russians and the Tlingit. Digitizing this historic hat was all the more significant because the theme of the conference, which ended just before the 150th anniversary of the sale of Alaska from Russia to the US, was ‘healing ourselves.’ With all three objects now digitized, one of the most significant chapters of Tlingit history is archived and, through 3D technology, available for the clan to explore and share in new ways.

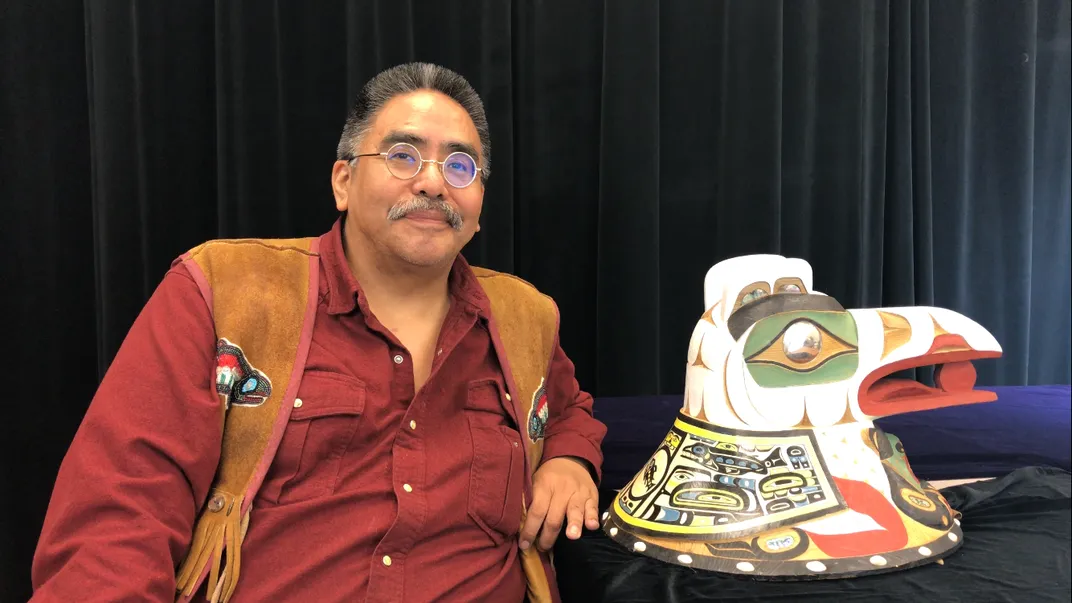

Not all of the objects we scanned were ancient, however. One of the most dramatic clan crests we worked with was the White Raven Hat. The hat’s caretaker, Lukaax.ádi clan leader Raymond T. Dennis, Jr. explains “It’s not an old hat, but it is a depiction of the old raven before it became black. Years ago my grandmother told us we need to start using the old white raven again.” Duane Bosch, a student of Tlingit master carver Jim Marks carved the hat out of red cedar. It was dedicated in 2010. Dennis would like to make another hat, ‘a brother hat’, a black raven, using the scan data from the White Raven hat. Dennis is acutely aware that he is creating a legacy for future generations. “One of these days, if not my nephews’ time, then their nephews’ time, [they will ask] what in the world was in great uncle Ray’s mind when he did this? And they’ll look at each other and say ‘you were in his mind.’”

Not only did we scan objects, we also demoed live 3D printing. In doing so, we showed conference-goers how physical objects can be remade from digital models and how readily available that technology is in the local community. The 3D printer we used was loaned to us by nearby Mt. Edgecumbe High School. The school has three such printers available to students, sparking ideas about new ways to engage younger generations in the history cared for by the clan leaders. As a demonstration at the conference, we brought 3D prints of shee aan, rare Tlingit throwing boards, sometimes called atlatls, which allowed conference-goers to try spear throwing with them as their ancestors had for hunting more than 200 years ago.

Preservation and perpetuation of their cultural heritage is of the utmost importance to the Tlingit community as their identity is inseparable from their clan objects. Applying 3D technology to indigenous objects not only provides insurance against future loss, but also facilitates knowledge sharing and helps restore cultural practices. Together, the Smithsonian and the Tlingit people are showing how advances in technology can be used to tackle some very old challenges to make sure the culture survives and thrives for future generations.