NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Check Out These Unexpected Connections in Natural and Presidential History

To celebrate President’s Day, here are some of my favorite natural history artifacts and specimens that not only form the foundation for scientific discovery, but also reveal a piece of the American story.

:focal(2880x1915:2881x1916)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/nmnh_170111_0933.jpg)

I came to work at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) with a background in American history and an expectation that natural history is purely science. I couldn’t have been more wrong. I quickly learned that a sizeable portion of the museum’s 145 million artifacts and specimens relate to American history—like those given to us by or on behalf of past presidents. To celebrate President’s Day, here are some of my favorite natural history objects that not only form the foundation for scientific discovery, but also reveal a piece of the American story.

1. Taft's Punch Bowl

If you are anything like me, you’ve always wondered what it would be like to wine and dine with the president. Well, if you were to do so in the early 20th century, you may have “wined” from this punch bowl with William Howard Taft. Made from a Tridacna (giant clam) shell—which could weigh up to 500 pounds and live 100 years—and mounted in a sea of silver mermaids, the punch bowl is part of a 32-piece set crafted by Filipino silversmiths, Fernando and Tomás Zamora around 1903. The set was exhibited at the Louisiana Purchase and Lewis and Clark expositions before being purchased and then gifted to the NMNH by then Secretary of War William Howard Taft in 1906—three years before he was elected president.

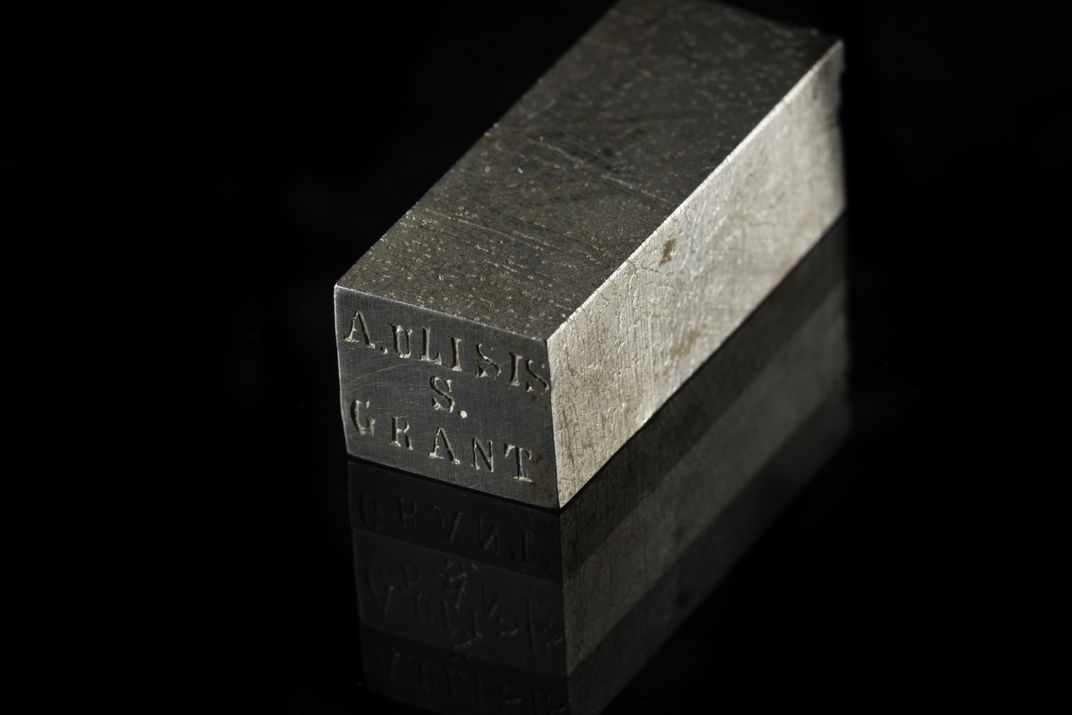

2. Grant's Meteorite

Some presidential gifts are from out of this world—literally. The Mexican government once presented this cut and polished sample of the Charcas meteorite—a large iron meteorite found in Mexico in 1804—as a diplomatic gift to President Ulysses S. Grant. Grant gave the meteorite to William G. Vanderbilt (owner of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the “richest man in the world”) as collateral for a personal loan on behalf of a friend in 1884—seven years after his presidency ended. When Grant died in 1885, Vanderbilt and Grant's widow, Julia Dent Grant, gifted the meteorite to the U.S. National Museum (now the NMNH) in 1887.

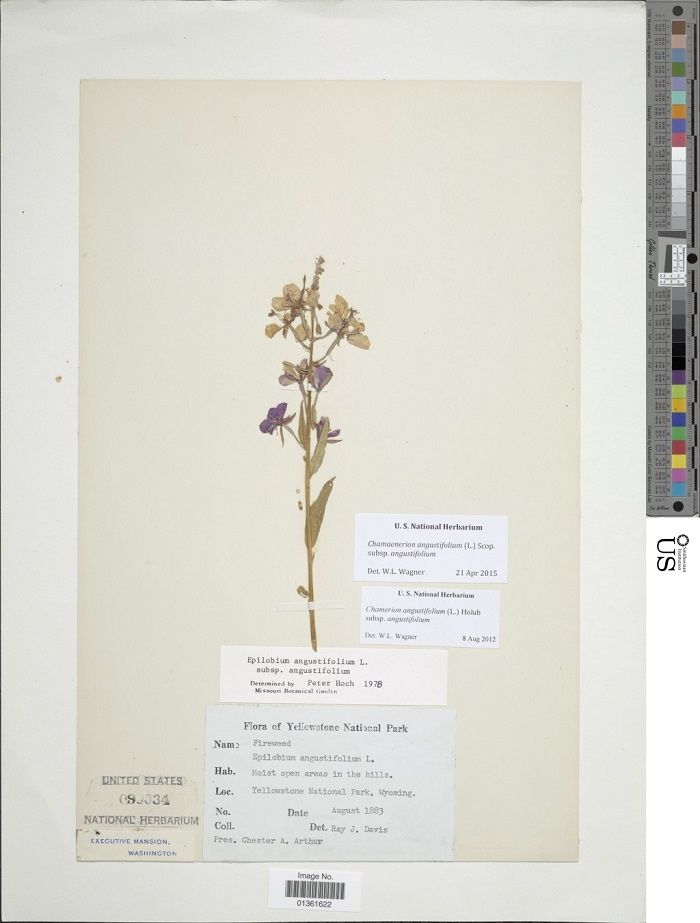

3. Arthur's Fireweed

Every once in a while, presidents stop to smell the roses—or in this case, fireweed. President Chester A. Arthur collected this specimen of fireweed (Chamaenerian angustifolium) in Yellowstone National Park in 1883. Fireweed is an angiosperm in the evening primrose (Onagraceae) family. Native to Canada and most of the United States, fireweed grows mainly in forest and alpine meadows, semi-shaded forests, and along rivers and streams. Fireweed is eye-catching in bloom, but why President Arthur—who had no particular interest in botany or natural history—would collect just one herbarium specimen and donate it to the Smithsonian remains a mystery. What is known is that out of the 5 million specimens in the U.S. National Herbarium, this fireweed is the only specimen collected and donated to the NMNH by a sitting president.

4. Buchanan's Saddle

Many of the artifacts and specimens associated with the American presidency were once diplomatic gifts from foreign governments—like the meteorite above and this saddle. In 1860, a Japanese delegation traveled to the U.S. to ratify the Treaty of Amity and Commerce which opened Japan to trade with the U.S. During their stay, the delegation presented this saddle to President James Buchanan on behalf of the “Tycoon” of Japan. The artifact’s records indicate that “Tycoon” was interpreted to mean the Emperor. But in the Edo Period of Japan, the word “Taikun” referred to the Shogun of Japan in his foreign relations role in order to convey that the Shogun was more important than the Emperor. Given this, the saddle is not only significant in that it represents the origins of U.S.-Japan relations, but it also provides researchers with insight into Japanese culture during the mid-19th century.

5. Theodore Roosevelt's Downy Woodpecker

I would be remiss if I did not also mention Theodore Roosevelt as he was a lifelong naturalist who gifted numerous artifacts and specimens to the NMNH. In 1882, then New York State Assemblyman Roosevelt wrote to the Smithsonian offering his childhood natural history collection which he referred to as the “Roosevelt Museum of Natural History.” The collection featured an array of insects, mammals, and birds including this Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens). The specimen bears Roosevelt’s original label which indicates that he collected and prepared the bird in 1872—at the young age of 13. The specimen is housed in the Division of Birds alongside several others collected by Roosevelt from his days as a young naturalist where it offers scientists valuable information about history and climate in the 19th century.

So, next time you want to learn something new about American history, your local natural history museum may be a resource for a unique telling of what might otherwise be a familiar story. Happy President’s Day!

Editor's note: The entry on Grant's meteorite has been updated to correct an innaccuracy in the gifting date. The cover photo caption has also been updated.