NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

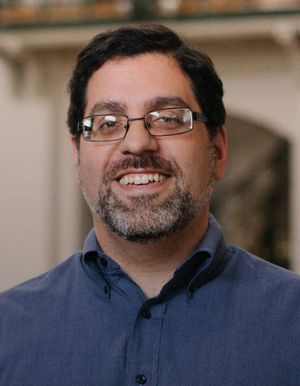

Q&A: Smithsonian Dinosaur Expert Helps T. rex Strike a New Pose

The Nation’s T. rex is back at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in a striking new pose.

:focal(966x264:967x265)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/NHB2017-00021-1200pixel.jpg)

The Nation's T.rex has come home. Unearthed in Montana in 1988, this Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton spent the last four years in Canada preparing for what could be more than 40 years in the spotlight. Now, the bones of America’s tyrant lizard are back at the National Museum of Natural History to preside over the renovated Hall of Fossils.

The arrival of the Nation’s T. rex marks the start of the final installation of the exhibit, called Deep Time, which will debut in less than one year on June 8, 2019. Matthew Carrano, the museum’s Curator of Dinosauria, is especially eager for the fossil’s homecoming and to see the 38-foot carnivore assume a predatory new pose he helped create.

At the center of the new exhibit, T. rex will sink its steak knife-sized teeth into the bony neck frill of a Triceratops it has pinned to the ground. The dramatic scene would be at home in the movies but it’s no cinematic flight of fancy--some excavated Triceratops skulls bear the telltale hole punches of T. rex teeth, says Carrano.

In the following interview, Carrano tells us more about how the T. rex’s new pose came about, what made it possible, and his personal connection to dinosaurs and the exhibit.

How did the idea for the T. rex’s new pose come about?

I came to the meeting about the T. rex pose with an agenda: I wanted to, in a realistic manner, conclude the narrative arc of our Triceratops, named Hatcher. As a specimen, Hatcher served us very well over the last 20 years, but I thought it was time to bring that story to a close.

We thought about having the T. rex posing next to the dead Triceratops. But it was important for them to be directly engaged. There is a sense of balance and tension in this pose. The T. rex’s leg is pressing down on the ribcage of this Triceratops, and if you look closely the ribs are slightly cracked. In fact, the T. rex is decapitating the Triceratops. You can see the head is being levered off the neck. There are lots of small details there for visitors who take the time to find them.

What made this new pose possible?

Working with Research Casting International (RCI) in Canada enabled us to expand the boundaries of what was feasible in the time we had.

Combining 3D scans of the fossils with the ability to 3D print them allowed us to 3D print a one-tenth scale model. Being able to test out slight variations of the pose made a big difference. We would reposition the feet of the Triceratops, adjust how high the T. rex’s flexed knee was relative to the ribcage, or how the T. rex’s tiny arms were hanging. It let us visualize changes to the pose in a way that computer programs just don’t.

That sort of thing wasn’t impossible 10 or 20 years ago, but it would have required much more time and effort.

Describe the moment when you first saw the T. rex’s new pose in person.

Seeing it there in front of me for the first time was almost too much to take in. We were all floored even though we came in knowing what it was supposed to look like.

It was like if I had built a house or something. I tend to not talk in those situations, so of course people were asking me if I liked it. It was like, “Yeah guys, I like it.” I probably went to RCI’s workshop four times to see it. I would just walk around in circles looking at it, taking the same pictures over and over.

After such a long process with so many people involved, it was actually better than I imagined it could be. This exhibit will stop people in their tracks.

Much of the T. rex skeleton that goes on exhibit will be real fossilized bone. How did you decide on using real fossils and how did the steel frame of the mount facilitate that?

Prior to 2014, the Smithsonian only had a cast of a T. rex skeleton. So, because we went through so much work to get this specimen it was never a question about whether we would put the real bones on display.

The original way skeletons like this were mounted was intended to be permanent. That meant drilling into the actual fossils, which was terrible for their preservation and also meant some of the fossils on display hadn’t been looked at by a scientist in 100 years. The mounts for the fossils in this new exhibit cradle the bones. This doesn’t damage the fossils and allows them to be periodically removed for study.

How does the new posture of these specimens fit into the larger picture of the exhibit?

We have several places in the exhibit where we put animals and plants together that are from the same place and the same time. The idea is to represent portions of real, extinct ecosystems. For T. rex and Triceratops that means Montana, North Dakota, or Wyoming about 66 million years ago.

Some of the other poses will leave visitors wondering why we decided to show what we did. My hope is that people will have questions. Like, “Why did you make that dinosaur do that?” A T. rex eating a Triceratops is exactly what you expect to see. But if you see a dinosaur sleeping, you start to think, “What’s going on? Why am I looking at this?”

I think you can turn that question into a new train of thought in a visitor: “That’s true, my cat sleeps 22 hours a day.” You start to think about things differently. That’s an undercurrent of the hall—we are trying to surprise our visitors. The T. rex is not surprising, but that’s not its job. Its job is to be awesome. Some of the other things in the exhibit I think will be pretty surprising.

How did you first get interested in dinosaurs?

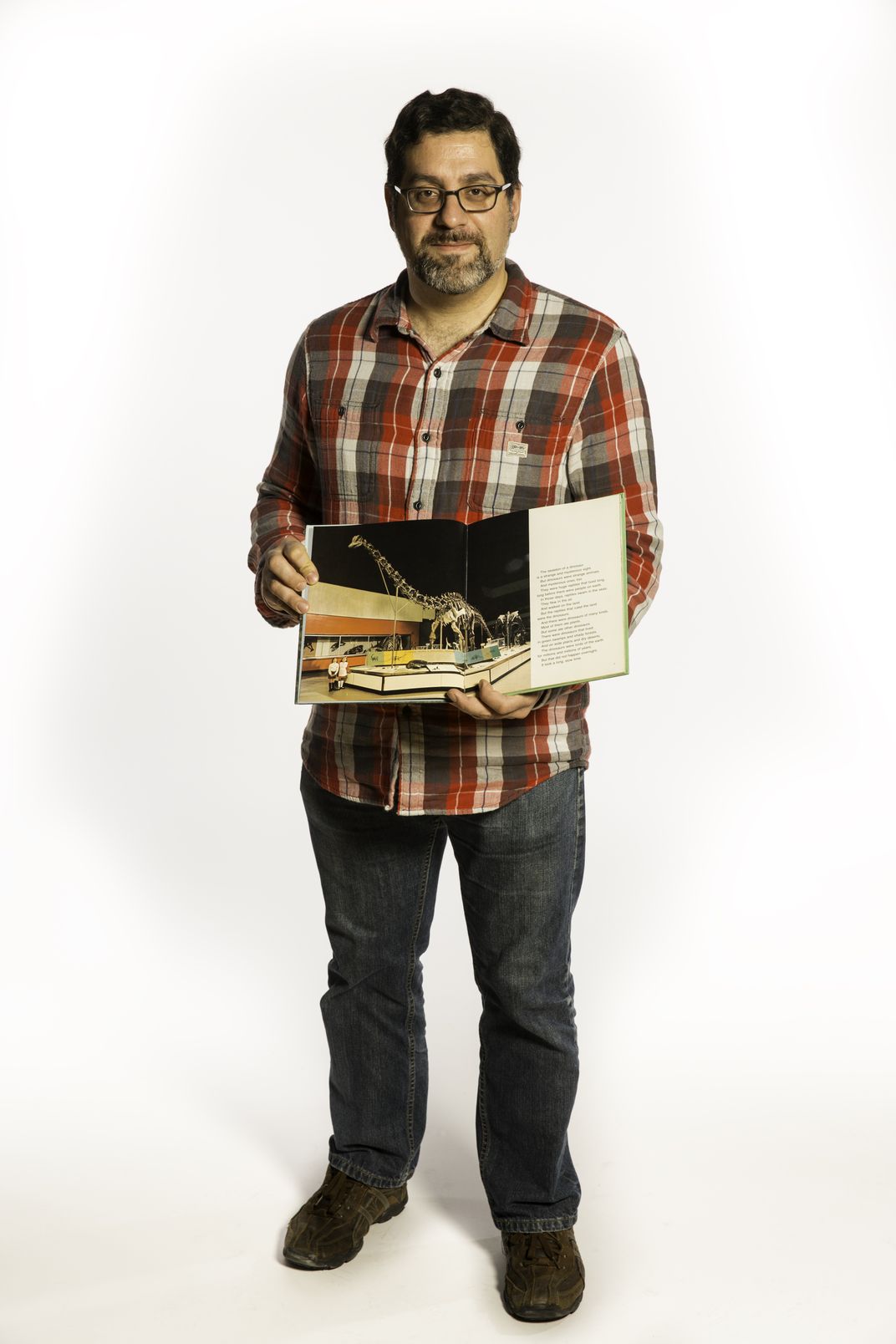

In second grade, a friend of mine was reading a National Geographic book on dinosaurs, and I was reading it over his shoulder. I’d never seen a picture of a dinosaur until then. I got obsessed pretty quickly.

I started visiting the library a lot and the Peabody Museum at Yale. It was a small and quiet museum. You could have it to yourself to sit and stare at the dinosaurs.

Between the museum and the library, those were the only ways you could see a dinosaur—it wasn’t like it is now where there are images of dinosaurs everywhere in popular culture.

Now, I collect vintage dinosaur children’s books. It’s quite easy to have all of the English-language dinosaur children’s books up to around 1985 on one shelf. There are probably fewer than 200. Now, it seems like there are that many published every year.

What do you hope the dinosaurs in this exhibit communicate to kids who might be seeing them for the first time?

I want the dinosaurs to seem like they were real animals. We tried to pose them doing things the scientific evidence suggests they really did. The old tradition was to portray dinosaurs standing still, and it makes them seem more like works of art--like objects. I don’t want our dinosaurs to look like objects, I want them to look like animals.

What does it mean to you to help shape an exhibit that will introduce millions of people from around the world to your life’s passion?

Helping shape an exhibit that will hopefully excite, inspire, or amaze millions of people over the next 30 or even 50 years is a very high privilege.

It’s funny, paleontologists always have the long view of things, but in terms of my own lifetime this exhibit will reach farther into the future than anything else I can do. There’s nothing I could write or dig up that would have the same impact that this will.

I didn’t expect to be here doing this, but I’m very grateful to be part of this project. It’s already the biggest possible deal for me, but I hope it’s also a big deal for people who come see it.