NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

An Elegy for Hatcher the Triceratops

Named in honor of the discovering paleontologist, Hatcher introduced Triceratops to the world, and was a pillar of the Smithsonian community for 113 years.

:focal(827x516:828x517)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Hatcher_Deep_Time3.jpg)

Hatcher is dead. The Triceratops was 66-million-years-old.

Named in honor of the discovering paleontologist, Hatcher introduced Triceratops to the world, and was a pillar of the Smithsonian community for 113 years.

Hatcher is survived by longtime frenemy Tyrannosaurus rex, who can be seen eating Hatcher in the “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils - Deep Time,” opening June 8, 2019.

Posed in death, Hatcher will bring an extinct ecosystem to life.

In 1905 “he,” as museum curators and staff have taken to personifying the dinosaur, became the world’s first Triceratops to go on exhibit. For more than 20 years, Hatcher remained the only displayed specimen of his species on the planet.

For those who knew Hatcher well, who cradled his bones and whose sweat and labor brought his skeleton to life, the herbivore’s passing represents the loss of a companion.

“I got to know every bone,” says Steve Jabo, one of the Smithsonian’s fossil preparators who molded and cast Hatcher’s skeleton beginning in 1998. “Hatcher became kind of like a pet.”

Even without physical contact, Hatcher cast a spell.

“I spent two years behind a computer, not touching him, but moving his bones digitally and making him come to life,” says Rebecca Snyder, a digital media specialist who helped digitize Hatcher’s skeleton in 1998. “Now that he’s dead in this new exhibit, it’s a little sad.”

Matthew Carrano, Smithsonian’s Curator of Dinosauria, says he’s already received emails from museumgoers upset about Hatcher’s death in “Deep Time.”

A life in the public eye

The beloved Triceratops was not without quirks, particularly during his first 90 years on exhibit.

When Hatcher first went on display in 1905, no complete Triceratops skeletons had been found. To create a complete skeleton paleontologists pieced together 10 different individuals.

The resulting specimen was a mashup of its fossil donors. Hatcher’s skull was too small for his body, his front legs were of different lengths, and his rear feet belonged to an entirely different species with the wrong number of toes.

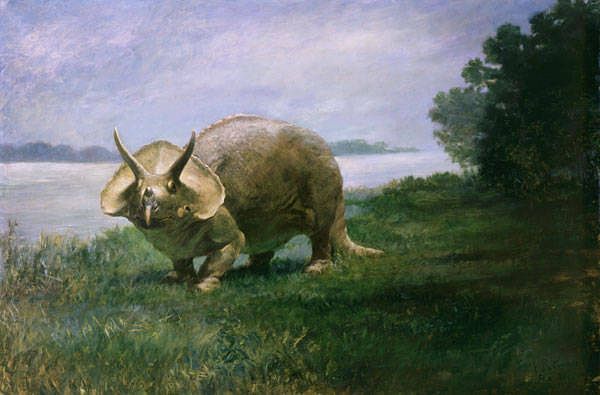

Hatcher’s posture was also less than regal. To match the turn of the century notion that he was a slothful swamp dweller, Hatcher’s front end was slung low and crocodile-like with his elbows nearly at shoulder level.

Hatcher was the centerpiece of what was then called the “Hall of Extinct Monsters.” He was posed without any suggestion of motion, like a pinned butterfly.

At the time, dinosaurs were seen as curiosities--sluggish evolutionary first drafts doomed by their own strangeness. “The way they were presented didn’t so much lend itself to opening up a window to science more broadly,” says Carrano. “It was more like, ‘look at these weird objects from the past.’”

The preparators of the day treated Hatcher’s bones more like building materials than priceless artifacts. He was locked into his uninspired pose by metal rods and screws drilled directly into his skeleton.

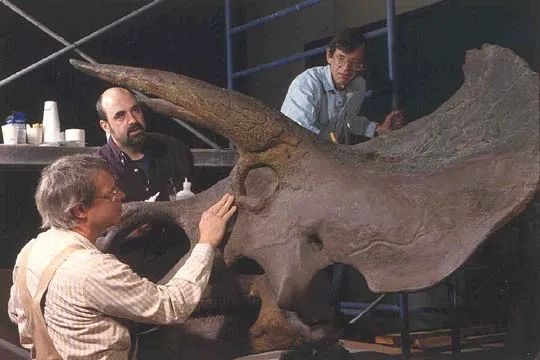

“The 1905 mount did irreparable damage to the fossil,” says Pete Kroehler, another fossil preparator who worked extensively on Hatcher in 1998.

Despite all this, Carrano says Hatcher was a star in his day and drew crowds to the museum.

Falling apart

In 1996, after more than 90 years of astounding visitors, Hatcher started to fall apart.

According to Kroehler, a visitor to the museum was admiring Hatcher when a chunk of his pelvis fell to the ground, to the dismay of a nearby security guard.

A closer look revealed Hatcher had a “disease.” The condition, called pyrite disease, occurs when exposure to increased humidity causes deposits of the minerals pyrite ("fool's gold") or marcasite (chemically identical to pyrite) inside the fossil to grow--breaking up Hatcher's bones from the inside.

In 1998, fossil preparators including Jabo and Kroehler took Hatcher off exhibit. They applied treatments to halt the advancing disease, and set about creating a new, more scientifically accurate mount.

Hatcher 2.0

The Smithsonian took advantage of Hatcher’s off-time to complete the first 3D scan of an entire dinosaur skeleton. This project allowed Hatcher’s out of proportion bones to be scaled up or down and facilitated the creation of a one-sixth scale model of the skeleton.

With the 3D scan completed and a physical model that could be easily manipulated, the Smithsonian hosted a symposium of the world’s top Triceratops experts. The group created a more upright posture for Hatcher that remains the scientific community’s best guess at how the dinosaur might have carried itself.

In 2001, Hatcher went back on display, posed with his head lowered and one leg raised to suggest he was turning to defend himself. In 2014, Hatcher migrated upstairs to the “Last American Dinosaurs” exhibit as the Fossil Hall underwent renovations for “Deep Time”.

What killed Hatcher?

Hatcher’s cause of death in “Deep Time” is unknown, says Carrano.

Suspiciously, the Nation’s T. rex is beginning to consume the three-horned dinosaur. But Carrano says unless new evidence comes to light, the Nation’s T. rex just as likely scavenged Hatcher after something else did him in.

In the forthcoming exhibit, the Nation’s T. rex has a foot planted on Hatcher’s rib cage. Several of his 6-foot ribs have cracked beneath the weight. Hatcher’s neck frill is in the T. rex’s mouth and his left horn is broken against the ground.

“The T. rex could be using this leverage to decapitate Hatcher,” says Carrano. “But, apart from those bits of damage, the rest of Hatcher is in good shape. To me this says he hasn’t been dead very long, but also doesn’t point to any one scenario for how he died.”

So far, emails Carrano has received about Hatcher’s death assume that T. rex killed him. “We were hoping people might come in assuming that and then be surprised to learn that it’s maybe not what happened,” says Carrano.

The mystery of how Hatcher died invites visitors into the mind of a paleontologist, looking for clues on the surface of the fossil bones.

Hatcher’s death also signifies a reprisal of what brought his remains to the museum in the first place. “For an animal to become a fossil, the animal has to die and it has to become deeply buried,” says Kirk Johnson, paleontologist and Sant Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “So, part of the story Hatcher is telling in this exhibit is that he’s on his way to becoming a fossil.”

A life well spent

Still, Hatcher’s grim tableau took some getting used to for those who spent years of their lives pampering his bones.

“Excuse the pun, but at first it was a bit of a bone of contention,” says Jabo. “But then I saw the new mount in person, and I was all in.”

For Snyder, who created 3D animations of Hatcher for the 2001 exhibit, a Triceratops couldn’t ask for a better legacy than the reactions the fossil elicited from kids.

“They would gasp and just start running towards Hatcher. It will be different, but I’m sure they’ll do the same thing in ‘Deep Time.’ He lived a good life.”

Related story: Q&A: Smithsonian Dinosaur Expert Helps T. rex Strike a New Pose