NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

A Smithsonian Dino-Celebrity Finally Tells All

The Smithsonian’s Ceratosaurus is finally giving up its secrets as it prepares for a long fight with a Stegosaurus in the “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils – Deep Time,” opening June 8, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Archival_Display_Image.jpg)

There are two sides to every story, but for more than 100 years one of the world’s most important dinosaur fossils offered paleontologists just one—its right. The first Ceratosaurus ever found was dug up only to be half-buried in the wall of the National Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Fossils, all but inaccessible to science.

Now, the Smithsonian’s Ceratosaurus is finally giving up its secrets as it prepares for a long fight with a Stegosaurus in the museum’s flagship exhibit—the “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils – Deep Time,” opening June 8, 2019.

The original horned lizard

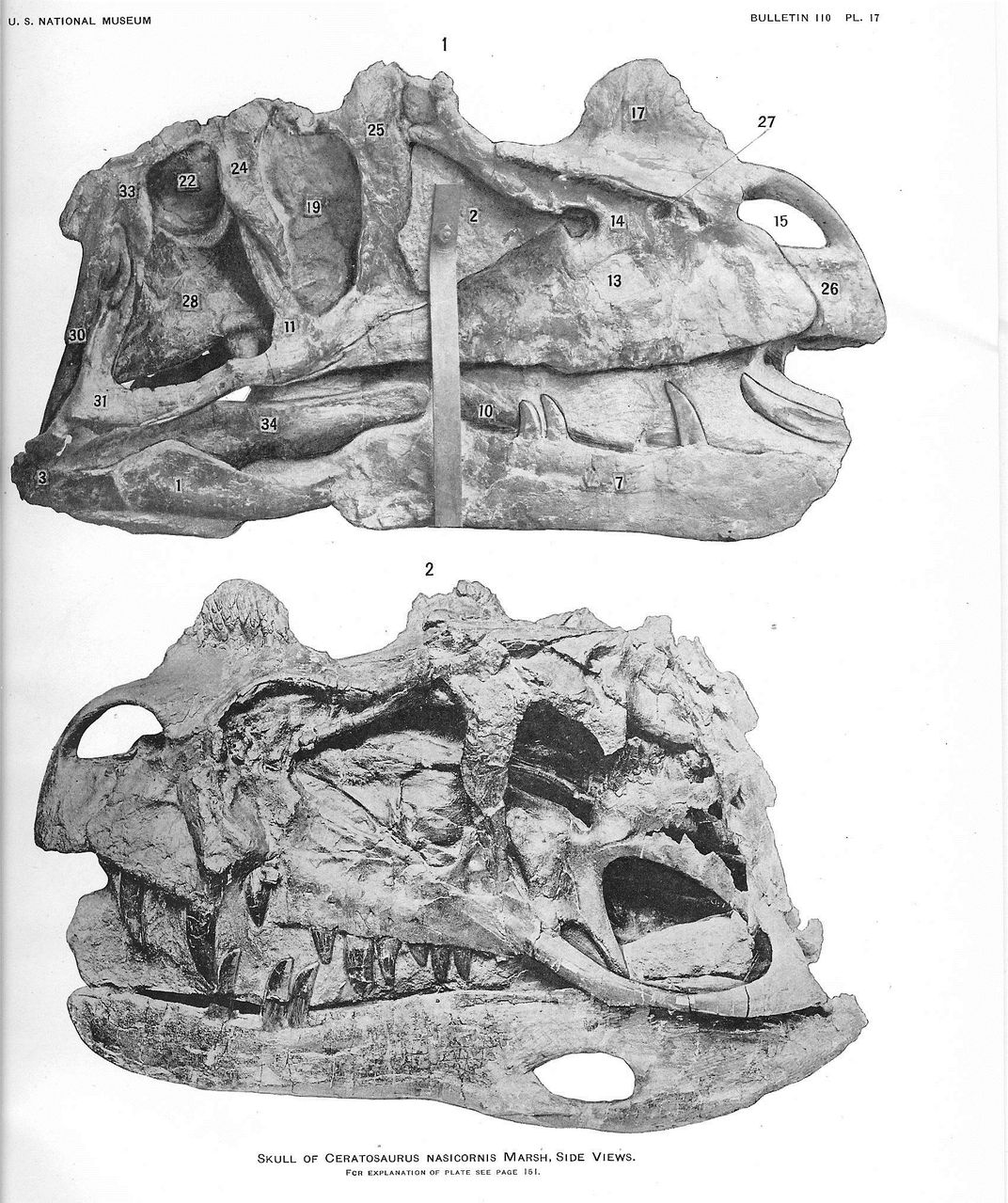

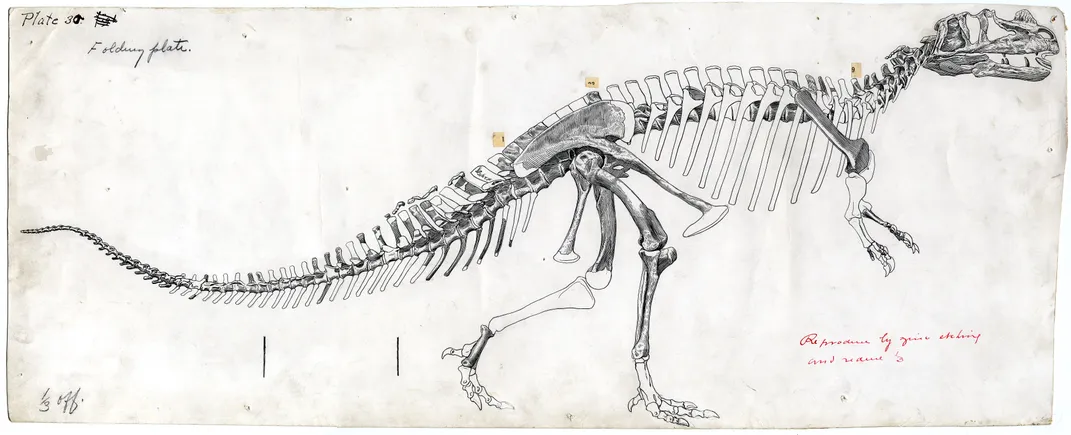

Ceratosaurus was a fearsome prehistoric predator. The 20-foot long Jurassic carnivore sported a face full of horns—one jutting from the tip of its nose and one above each eye—to go with long, blade-like fangs and a row of bony armor down its back.

But despite its ferocious appearance, few outside the paleontology community know it by name. Ceratosaurus hasn’t achieved the minor celebrity of Jurassic contemporary Allosaurus, let alone the kingly stature of Tyrannosaurus rex.

This is largely because their skeletal remains are rare compared to the larger and more ubiquitous Allosaurus and T. rex. Its rarity in the fossil record makes individual specimens that much more important, and until 2014 the most important specimen of them all was nearly impossible to study.

What makes the Smithsonian’s fossil so special is that it’s what paleontologists call a type specimen. This means that Ceratosaurus was first named and described using these ancient bones. It also means any unearthed remains looking for Ceratosaurus bona fides are compared to this skeleton.

“It’s like the original copy of the constitution,” says Hans-Dieter Sues, the Smithsonian’s Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology. “This is the gold standard for Ceratosaurus—a hugely important reference and a true treasure of the museum.”

If these walls could talk

The specimen was first excavated in 1883 in Fremont County, Colorado by Marshall Felch. The skeleton was dug up in huge sandstone blocks and sent back east by railroad. After a time in the collection of preeminent paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh at Yale University, the Ceratosaurus arrived at the Smithsonian.

Former Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Charles Gilmore and fossil preparator extraordinaire Norman Boss opted to reveal just of half the nearly complete skeleton for exhibition. They did this because when the nearly complete skeleton was found, its bones were mostly assembled in a serviceable posture. This saved untold hours working the bones free from the bullet-hard sandstone that preserved them.

After Gilmore and Boss prepared the right side of Ceratosaurus for display it was built into the very wall of the exhibit hall in 1911. The fossil bones were held together with a combination of 150 million year old rock and turn of the century building materials.

For more than 100 years the fossil that defined this ancient species stayed behind glass in the old fossil hall—known more intimately by museumgoers than by scientists.

“This super important fossil was stuck in the wall,” says Steve Jabo, one of the Smithsonian’s current fossil preparators. “Kind of like Han Solo frozen in carbonite.”

In 2014, the entire Fossil Hall closed to the public to facilitate the largest renovation in the history of museum. Once the creature was loosed from the walls of the museum, Marsh and Boss’ modern-day counterparts like Jabo and Curator of Dinosauria Matthew Carrano could finally uncover what lurked behind the plaster.

The first layers broke away easily, but beneath the white veneer, huge chunks of untouched Colorado sandstone sealed in the fossil’s left side.

“It was a big surprise to find so much sandstone,” says Jabo. “We thought they had prepared most of the specimen and just embedded it in plaster for display.”

The revelation that the skeleton would need to be chipped out of the tough-as-nails sandstone extended the timeline for its preparation. But it also meant discovery lay ahead.

Jabo and others spent more than a year at work on the Ceratosaurus in the fossil preparation lab, which is as much an art studio as it is a lab. To get in the mood for such exacting, delicate work, Jabo would listen to opera, particularly Puccini’s arias.

With Puccini in his earbuds, Jabo drilled, chipped and scraped at the sandstone with what look and sound like nightmarish dental tools--careful not to damage the irreplaceable fossil beneath.

New discoveries

Paleontologists like Carrano, couldn’t help but salivate. “This is the specimen I’ve been most anticipating getting to work on,” says Carrano. “Partly because I’ve been studying this group of dinosaurs for 15 years, partly because this is the type specimen and also because Ceratosaurus is a personal favorite of mine.”

By interrogating these bones one by one, Carrano hopes to modernize this species’ nearly 100-year-old scientific description and answer nagging questions. First on his list: how old was this creature when it bit the dust?

“We can take small cross sections of bone and count growth rings like a tree,” says Carrano. Fused bones in the dinosaur’s feet were formerly taken as evidence of adulthood, but Carrano thinks they may instead be the result of disease or injury. “My prediction is that we’ll learn our specimen is a teenager.”

Down but not out

Isolating these bones from the sandstone won’t just allow a glimpse into the past, it will also help introduce this carnivore to museumgoers of the future. Each bone is being molded and cast by Jabo and the fossil preparation team for Ceratosaurus’ pose alongside Stegosaurus in “Deep Time”.

Ceratosaurus’ shot at the limelight may come at the cost of its pride. The horned lizard will be flat on its back, legs flung up toward the sky to defend itself. A none-too-pleased Stegosaurus has just knocked the carnivore down with its spiked tail—this attack has not gone according to plan.

Visitors with an eye for detail will notice Ceratosaurus’ spine hovering just above the ground. Directly against the ground will be the bony knobs, called osteoderms, which run down the animal’s back and float a short distance above the backbone.

The scene is a counterpoint to the Nation’s T. rex munching on Hatcher the Triceratops nearby, to create a more well-rounded picture of these ancient predators. “Predators often fail in trying to bring down their dinner,” says Carrano. “Hunger might have forced this Ceratosaurus to take a bad chance.”

As the public wonders how the rest of this Jurassic drama will unfold, scientists too will be hotly anticipating what comes next as they begin to study this star specimen. Carrano says study of the Ceratosaurus is likely to begin early next year.

After 100 years on display, this old dino might just have a few new tricks left.

“Once you get to work with a fossil like this up close you inevitably find things you didn’t expect,” says Carrano. “I’m definitely anticipating surprises.”

Related stories:

An Elegy for Hatcher the Triceratops

Q&A: Smithsonian Dinosaur Expert Helps T. rex Strike a New Pose