NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Check Out Some of Our Most Popular Discoveries From 2018

Celebrate the new year with some of our most popular scientific discoveries from 2018.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/hannah_wood_-_dsc_0846_e.workmani_by_nscharff.jpg)

This year was well-traveled, across both time and space. Venturing to crossroads of the past, the vast heart of museum fossil collections, and mysterious underwater depths, our researchers returned with their notebooks and hearts brimming with discoveries. These stories teach us about our origins in the natural world and our active role within it. Join us on a journey through some of our most popular discoveries from 2018.

1. Early Humans Developed Social Skills Thousands of Years Sooner Than We Thought

We’ve made it through another year! To celebrate the start of a new one, a slew of discoveries on the origin of our species remind us that truly, “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

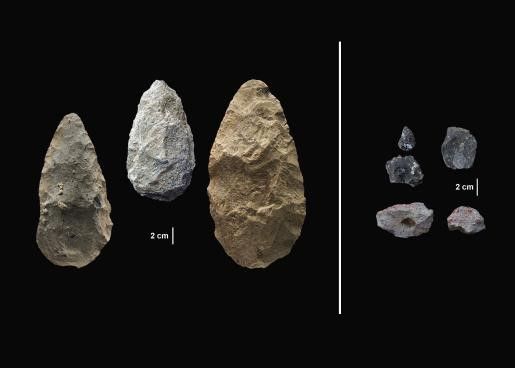

In three studies published in Science, a team of scientists, including NMNH researchers Richard Potts, Kay Behrensmeyer, Scott Whittaker, Jeffrey Post and Jennifer Clark discovered that environmental turmoil in the form of earthquakes and rapidly changing climate likely drove early humans in East Africa to develop social networks and new technologies by 320,000 years ago, tens of thousands of years earlier than we thought. The team found smaller, more precisely crafted stone tools and red and black rocks in the Olorgesailie Basin in Southern Kenya. The colored rocks were much too bright for everyday use, and may have been used as early symbols of rank or affiliation. Surprisingly, these resources were most likely obtained through trading networks spanning up to 55 miles away from the site.

2. Sexual Selection Could Cause Extinction

It may be time to make some ambitious New Year’s resolutions, but fossil crustaceans remind us “everything in moderation” may pay off in the long run—namely, when it comes to the size of reproductive organs.

For years, evolutionary biologists have pondered whether a physique to die for is truly worth dying for. Flaunting attractive traits can promote a healthy gene pool, but investing too much energy in securing a mate may reduce overall population fitness. NMNH paleobiologists Gene Hunt and M. João Fernandes Martins and their colleagues turned to the fossil record for answers. They discovered that male ostracods—a group of tiny, bivalved crustaceans—that invested the most in mating were ten times more likely to become extinct than those that were more conservative.

3. Scientists Plan to Sequence Genomes of All Eukaryotic Species

Speaking of ambitious resolutions, here’s one that we hope comes to fruition! An international team of scientists including NMNH researchers John Kress and Jonathan Coddington plans to sequence the approximately 1.5 million genomes of all known eukaryotic species—organisms whose cells contain a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles.

Currently, the genomes of less than 0.2% of eukaryotic species have been sequenced, and time is running out. In less than 40 years, up to 50% of the current species on Earth could be extinct, largely due to human activities. Thankfully, genetic data from the Earth BioGenome Project will help inform biodiversity conservation, technological innovation, and our understanding of the natural world.

4. 18 New Species of Madagascan Pelican Spiders Discovered

Plan to freshen up the feng shui of your home in the New Year? NMNH entomologist Hannah Wood and a colleague from the Natural History Museum of Denmark also did some reorganizing—of the taxonomy of Madagascan archaeid spiders!

The two researchers created the new genus Madagascarchaea and modified the genus Eriauchenius, describing 18 new species overall. Thanks to Madagascar’s geography and turbulent climatic history, new discoveries of unique archaeid species on the island are still common. Soon, this may no longer be the case, as continuing deforestation threatens Madagascar’s extraordinary biodiversity.

5. New Ocean Zone Sheds Light on Deeper Reef Ecosystems

Though a sunny day at the beach may be months away, our knowledge of deep reef ocean ecosystems is brighter than ever. NMNH curator of fishes Carole Baldwin and her colleagues named a new ocean zone as a part of the Smithsonian’s Deep Reef Observation Project (DROP).

The “rariphotic” (low light) zone lies between 130 and 309 meters below the water’s surface and is represented by a unique assortment of fishes, determined by more than 4,400 observations of 71 species. This finding sheds light on deeper reef zones, which may serve as sanctuaries for fishes escaping the worsening conditions of shallow reef ecosystems as a result of human activities like pollution, overfishing and climate change.

6. Anemone-Wearing Blanket-Hermit Crab Turns Out to be 7 Distinct Species

If you’re feeling a bit chilly this winter season, a discovery made earlier this year by one of our research zoologists Rafael Lemaitre and his team ought to warm you up. The blanket-hermit crab, long thought to be a single unique species of the genus Paguropsis, is a hermit no more!

Scottish naturalist J.R. Henderson first described and named Paguropsis typicus using specimens collected on the HMS Challenger Expedition in 1873-76. By studying these and recently collected specimens, Lemaitre and his team found that what was thought to be a single species from the Indian and Pacific Oceans actually comprises seven different species, five of which are new.

Blanket-hermit crabs are notable for their symbiotic relationships with sea anemones, which the crabs can grasp—using specialized pincer-like appendages—and pull over themselves for protection in lieu of shells. 130 years later, and thanks to the dedication of researchers and collections managers worldwide, the taxonomy of the blanket-hermit crab is better understood. Now it can tuck itself into its anemone and rest easy.

7. Mass Digitization Unlocks Potential for New Research in Museum Fossil Collections

Given the many incredible discoveries of 2018 by our researchers, you may be surprised to learn that much of NMNH’s growing collection of more than 146 million objects has not yet been published on. This seems to be a trend across the world’s museums. Collections manager Kathy Hollis and informatics manager Holly Little from our Paleobiology department were part of a team that estimated only about 3-4% of known fossil collection sites represented in museum collections are reflected in the Paleobiology Database (PBDB), the most representative international fossil research database.

Museums across the world are unearthing this paleontological “dark data,” inaccessible information embedded in museum fossil collections, through large-scale digitization efforts. These efforts mark a second digital revolution in the field of paleontology. As dark data is brought to light, so will our knowledge of the distant past, which can tell us more about our future.

Cheers to the New Year! Don’t be afraid to turn over a new leaf, and perhaps take a peek underneath—you never know what surprising discoveries await!

Related stories:

Here's How Scientists Reconstruct Earth's Past Climates

Countdown to the New Year: 7 of Our Favorite Discoveries from 2017