NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Old Fossils, New Meanings: Smithsonian Exhibit Explores the History of Life and What it Means for Our Future

For Earth Day, Smithsonian paleobiologist Scott Wing reminds us that we can look to the fossil record to better understand how ecosystems and organisms today respond to human-caused global changes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Wing_in_the_Field.jpg)

I was probably five years old when I first reconstructed a prehistoric scene. I molded a lumpy landscape from the Mississippi River mud in my backyard and populated it with plastic dinosaurs munching leaves I had snapped off our hedge (sorry Dad!). Like anyone’s, my life has had plenty of unplanned twists and turns, but it wasn’t an accident that more than 50 years after making my first diorama, I was sitting in a well-worn conference room at the Smithsonian helping plan the first complete renovation of its fossil hall since the Natural History building opened in 1910.

As children, we—the scientists charged with planning the content for the exhibition—were fascinated by ancient landscapes and creatures, but as adults and museum paleontologists, we had to ask ourselves what the grand themes of this new exhibit should be. What were the most important scientific developments in paleontology since the last upgrade 30 years before? What ideas did we hope millions of visitors to the hall would take home? Why, beyond sheer curiosity, should any of them care about the history of life? Helping guide this exhibit renovation has fulfilled my boyhood dream, but the themes of the exhibit are ones I would have never imagined as a child. They speak to a scientific revolution in how we think about the Earth, the fossil record and even ourselves.

The old fossil hall had few overarching themes. It answered questions like: How did extinct creatures live? When did certain features evolve? Who is related to whom? Past environmental changes were illustrated in only a few places. By contrast, the new hall will emphasize the ways Earth’s changing environment has affected evolution and ecosystems through time.

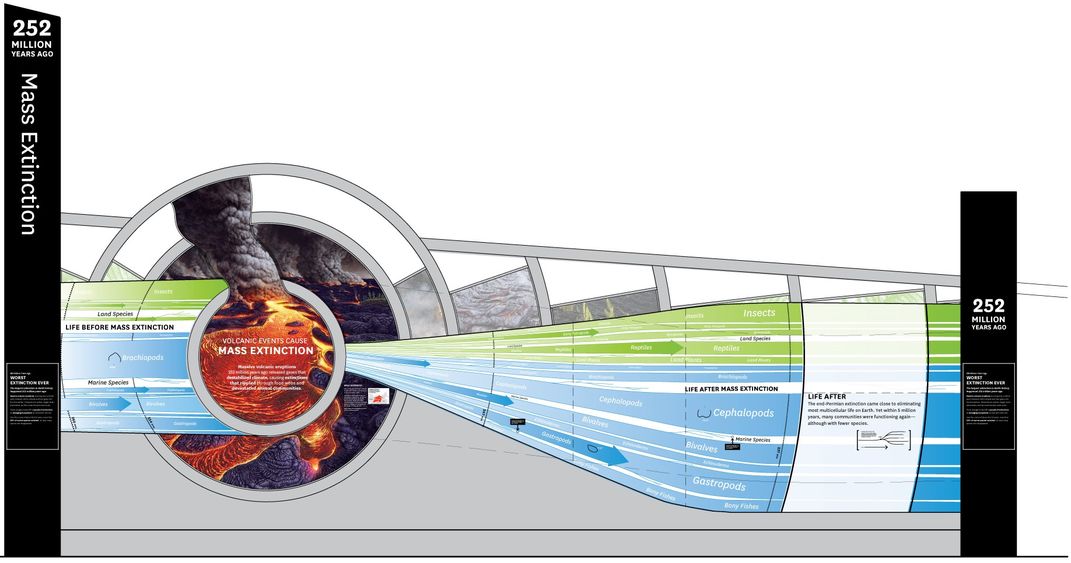

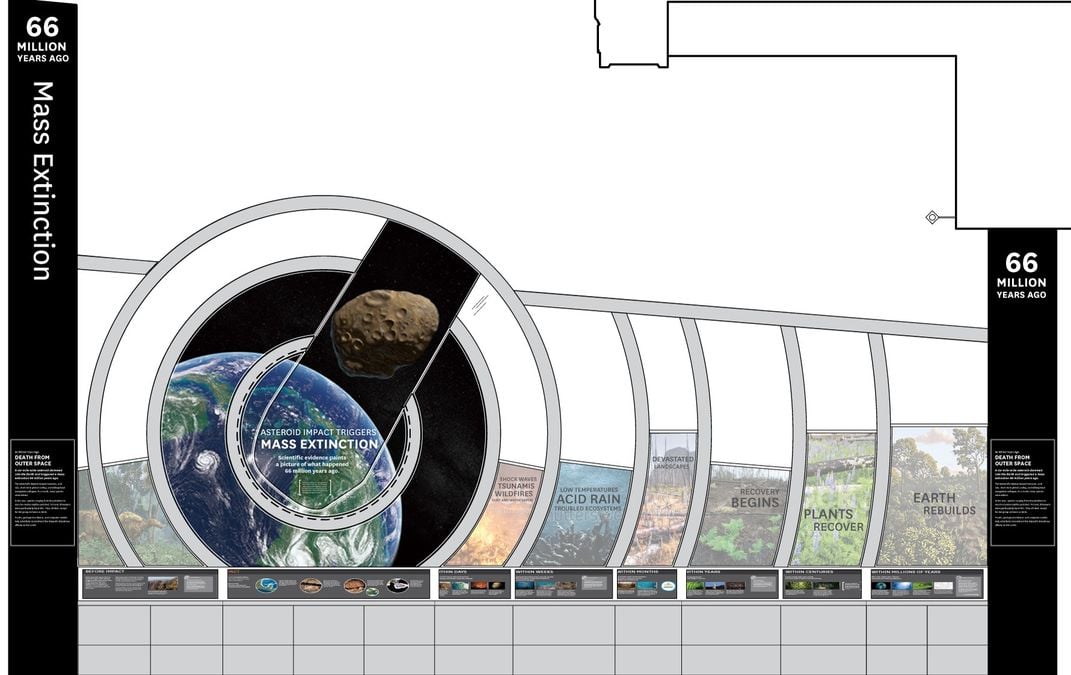

Free-standing walls jutting across the exhibit symbolize the two biggest mass extinctions in the history of life—at the end of the Permian, about 252 million years ago, and at the end of the Cretaceous, about 66 million years ago. Displays on the end-Permian extinction explain the huge pulse of volcanic activity that changed climate and ocean chemistry so radically that perhaps 90% of common marine animal species went extinct, and diversity took millions of years to recover. At the end-Cretaceous wall, we describe how consequences of a giant asteroid impact rippled through environments globally, changing climate, ocean chemistry and productivity and driving extinction of perhaps 75% of species.

Other areas of the new hall also feature the relationship between Earth’s environments and life. There is a panel on the global hothouse period—56 million years ago—called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, when a rapid release of billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere brought warm temperatures to the poles, changed ocean chemistry and played havoc in many ecosystems. Another area traces the expansion of human populations out of Africa in the last few hundred thousand years and how the arrival of humans is associated with the extinction of the largest land animals. One video shows how ice cores document coordinated cycles in atmospheric CO2 and global temperature during the last million years. And there is even a video that uses an animated, steampunk-style machine of tubes and containers to illustrate how the global carbon cycle operates and how we have changed it.

We highlighted these episodes and processes not only because they are important, but also because they help us understand how ecosystems and organisms today respond to human-caused changes. Paleontologists now study the past with an eye on understanding the future, and though describing the history of life is still our bread and butter, we have the added goal of using that history to shine a light on events to come. Many of the changes humans are causing now are similar in magnitude to major events in the history of life, but the changes we cause are far faster. Further, the past shows us that the carbon cycle—something we are changing radically—has amplified many past dramas.

When the “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils – Deep Time” opens on June 8, most people will call it “the new dinosaur hall,” and for good reason—awe-inspiring dinosaur skeletons will be the stars of the show. But the theme of the new exhibit concerns the future as well as the past.

Life on Earth has survived global ice ages and saunas, changes in the composition of the atmosphere driven by volcanic cataclysms and impacts of giant rocks from space. But the survival of life in the face of global disruptions should not reassure us. When the planet changed a lot, and especially when large changes came quickly, species went extinct, ecosystems failed and it took geological time for the Earth’s systems to regain function. Rather than making us comfortable with human-caused global change, the exhibit lays bare the hardship of living through times of rapid change.

Every visitor who comes to the new fossil hall has inherited a 3.7-billion-year-old legacy – the living system they depend on. The new hall puts our time in the context of deep time, helping people see that their actions today leave a legacy that ripples thousands of generations into the future. My childhood dream was to make models of the Earth’s past. Now, I hope to help visitors learn what the past tells us about the future, and how to manage the geological-scale effects we have on the planet that supports us.

Related stories:

Here's How Scientists Reconstruct Earth's Past Climates

Can You Help Us Clear The Fossil Air?

Leading Scientists Convene to Chart 500M Years of Global Climate Change

Q&A: Smithsonian Dinosaur Expert Helps T. rex Strike a New Pose