NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Megalodon May Be Extinct, but There’s a Life-size One at the Smithsonian

A 52-foot, life-size model of a Carcharocles megalodon shark is now on display in the National Museum of Natural History’s newly opened dining facilities.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/First_Image.jpg)

Between 23 and 3.6 million years ago, dorsal fins taller than a modern-day human protruded from the warm waters surrounding Washington, D.C. Such fins belonged to a formidable shark who once prowled the Chesapeake Bay region and oceans around the world: Carcharocles megalodon.

Today, a life-size model of the now extinct predator hangs from the ceiling above the National Museum of Natural History’s new Ocean Terrace Café. Visitors entering the café from the Ocean Hall come face-to-face with one of the largest and most powerful animals to have ever lived on Earth.

A fearsome killer

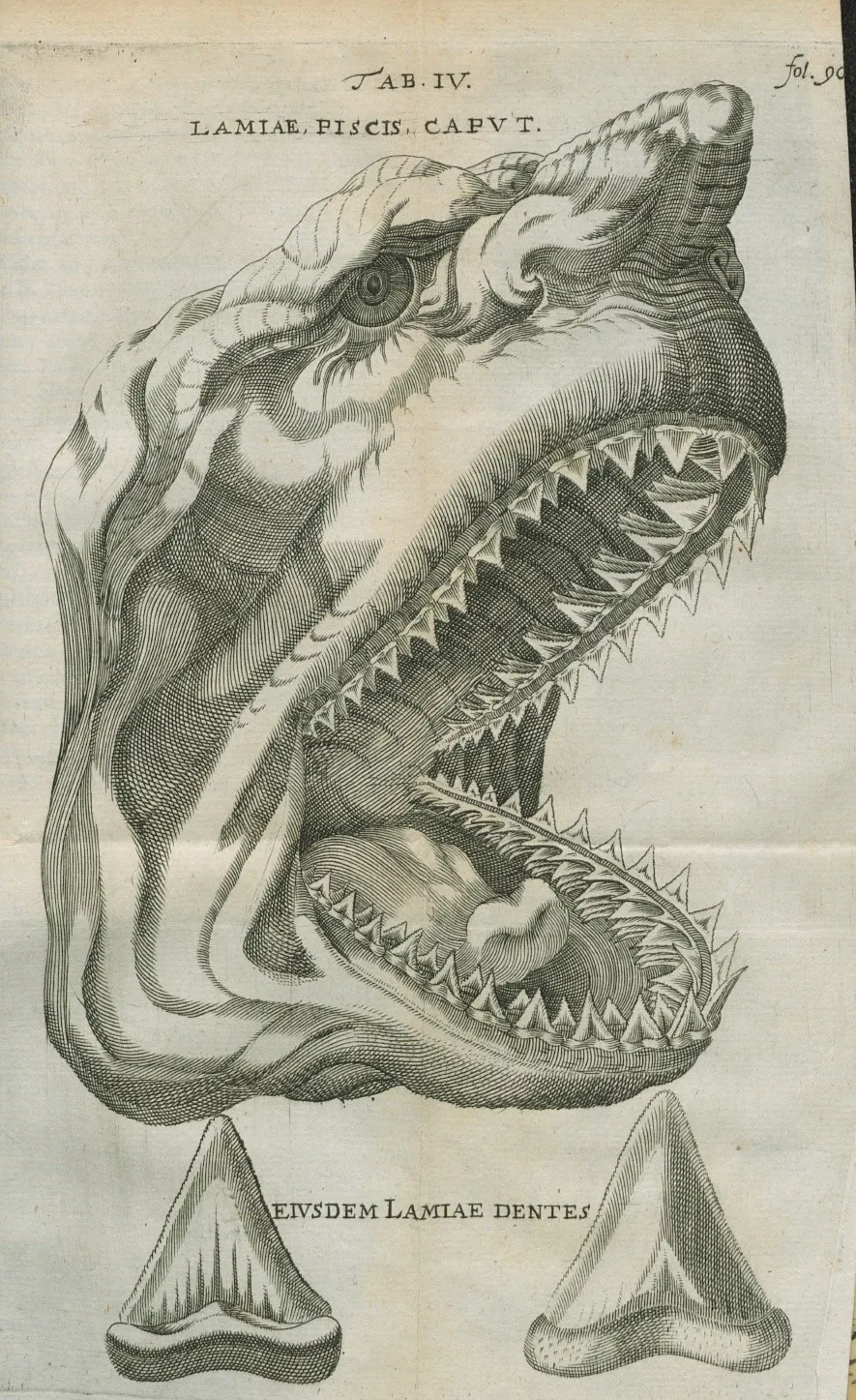

C. megalodon, often called simply “megalodon,” is famous for its massive size and sharp teeth. Its name in Greek means “big-toothed glorious shark” – a fitting moniker for an immense and deadly hunter with chompers as big as a human hand.

As the top predator of its day, megalodon feasted on small whales, sea turtles, seals and large fish in shallow seas around the globe. Its serrated teeth were handy for slashing through skin, fat, muscle and bone as it ambushed its prey from the side or from below. An average tooth measures around 5 inches from base to tip. The largest are around 7 inches long.

Coupled with these saw-like teeth was an extreme bite: megalodon’s jaws generated 40,000 pounds of bite force. In comparison, saltwater crocodiles – award winners for living creature with the strongest bite – tear into their prey with around 3,700 pounds of force per square inch. Humans bite into a steak with only 150 – 200 pounds.

“There is nothing today that comes anywhere close,” says Hans-Dieter Sues, one of the Smithsonian’s Curators of Vertebrate Paleontology. “Even Tyrannosaurus rex doesn’t come close to that amount of pressure”

Then around 3.6 million years ago, Earth’s biggest shark disappeared.

Most of the shark’s skeleton was composed of cartilage, which rapidly decays and doesn’t leave behind fossils. Now, all that remains of the magnificent megalodon are teeth, vertebrae and petrified poop.

Giant of the seas

In the 17th century, people believed fossilized megalodon teeth could counteract toxins and kept them as amulets, called “tongue stones” or glossopetrae. When Danish naturalist Nicholas Steno dissected a great white shark’s head in 1666, he realized that tongue stones were in fact prehistoric shark teeth that belonged to something much bigger.

Fossil vertebrae that look like gigantic ashtrays gave scientists the first idea of megalodon’s size. A partial backbone uncovered in Belgium in the 1920s had at least 150 vertebrae.

Female megalodons outsized males – a common feature among sharks. A female may have reached up to 60 feet in length and weighed up to 120,000 pounds. Males, on the other hand, were up to 47 feet long and tipped the scales at up to 68,000 pounds.

The Smithsonian’s megalodon model is a female measuring 52 feet. Her size is based on a set of teeth uncovered in the Bone Valley Formation in Florida in the 1980s – the largest of which are 6.2 inches long.

“Most people have never been close to a shark like megalodon,” Sues says. “They’ll have an idea from the movies for what a shark looks like, but they won’t have seen one up close unless they’ve gone scuba diving.”

Building the beast

The museum’s megalodon is suspended beneath panels of windows, where sunlight streams in to brighten her bronze back. Her mouth is open for visitors to glimpse three full rows of serrated teeth on her bottom jaw and two on the upper.

Megalodon is not in an attack pose, ready to catch lunch. If not for the cables holding her in place, she might be idly swimming toward the viewer – though the 2,000-pound model still looks menacing.

“I was mindful that there might be little kids who would never go in the ocean if the model was too scary,” Sues says.

The behemoth’s body is based on a large group of related species – including great whites and salmon sharks. But megalodon’s closest relatives are not great whites, as many scientists once believed. Mako sharks are the best living representation of its extinct cousin, albeit much smaller.

“A mako shark would look puny next to a megalodon,” says Sues. But the fish is still large by human standards; Sues has a set of mako jaws at home and he can easily fit his head in its mouth.

Sues and his colleagues, including artist Gary Staab, worked with experts to guarantee that the model depicted an active predator with the right shape to fit its lifestyle chasing whales. Where great whites have incredible girth, megalodon is more streamlined to match makos – the fastest sharks in modern oceans.

“Sometimes when you see megalodon reconstructions, they look like great whites on steroids,” Sues says. “But I don’t think that’s very likely because that kind of blimp would have a hard time swimming around and catching prey.”

Megalodon is definitely extinct

Pop culture has latched onto megalodon as a highlight for thrilling ocean-themed tales. The ancient shark has been featured in novels and films. Mockumentaries on Discovery Channel’s annual Shark Week have prompted conspiracy theories that megalodon is somehow still surviving in the deep sea, evading detection. Another misconception is that the shark lived at the same time as T. rex, though a gap of 43 million years separates the two species.

In the 2018 film The Meg – based on a novel by Steven Alten – megalodon resurfaces from the deepest part of the ocean to terrorize a research vessel.

“It’s completely impossible because megalodon swam in shallow, coastal waters. The animal would implode at that depth,” says Sues.

But if it were possible, he thinks the film’s shark was nevertheless doomed. “When I saw that the meg was up against Jason Statham, I knew that it had no chance,” he says.

Despite such fictional suggestions, megalodon remains extremely extinct. Changes in the ocean environment likely led to its disappearance.

Earth’s oceans cooled as ice caps formed at the poles. North and South America connected via the Isthmus of Panama, blocking circulation between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Megalodon’s favorite prey – small whales – vanished and it had to compete with other hunters such as the predatory sperm whale Livyatan and modern great white sharks. By 3.6 million years ago, megalodon was gone.

Though the glorious big-toothed shark is no longer around – and lived long after the dinosaurs – it is still a wonder to behold. Just steps away from the café’s life-size model, Smithsonian visitors can take a selfie with enormous megalodon jaws.

Megalodon has a fascinating history -- which makes it hard for Sues to pick his favorite thing about them.

“I’m generally very partial to meat-eaters,” he says. “Sharks are just amazing animals.”

Related Stories:

Q&A: Sea Monsters in Our Ancient Oceans Were Strangely Familiar

Can Technology Bring the Deep-Sea to You?