NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Scientists Describe New Bird Species 10 Years After First Reported Sighting

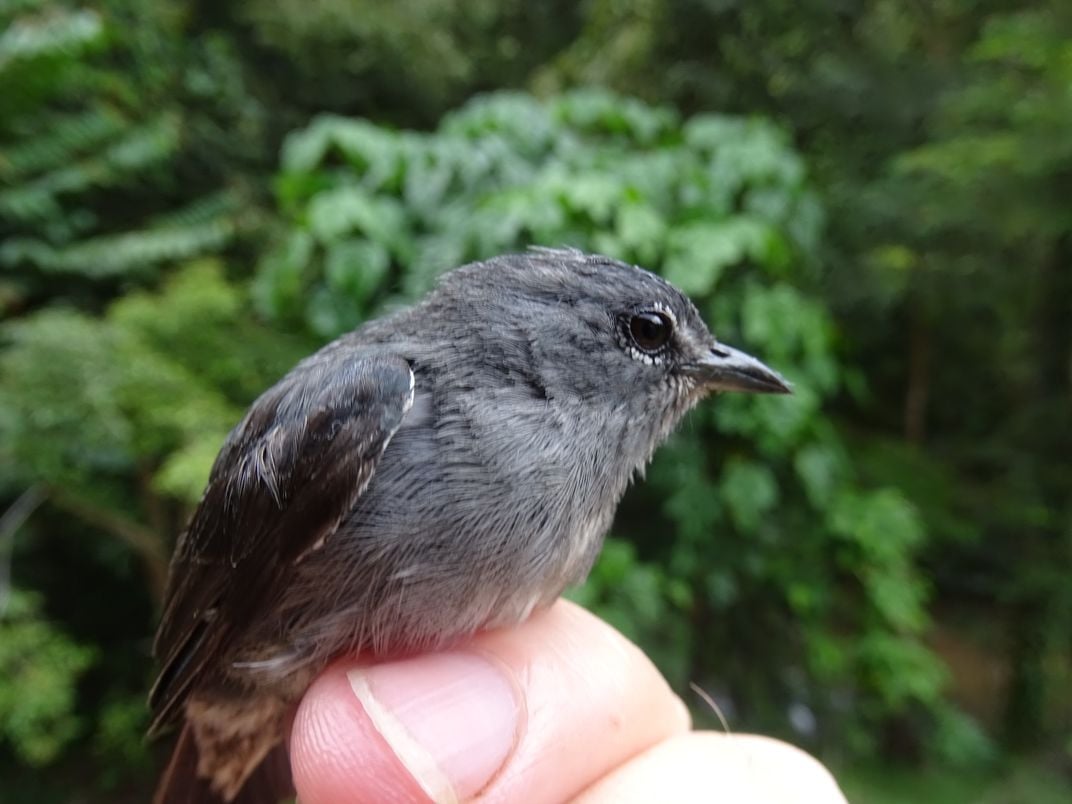

In an article published today in the journal Zootaxa, Smithsonian researchers described the spectacled flowerpecker after a decade of only scattered sightings and photographs of the small gray birds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Chris__Milensky_-_SFP_print003_17cmx25cmx300dpi_horizontal.jpg)

Smithsonian researchers Jacob Saucier and Christopher Milensky relied on Borneo natives to get them safely up the whitewater rivers in the Malaysian state of Sarawak. It took about two and a half days of traversing dirt roads and rivers to reach the remote lowland forests field site. Little did the team know, they would finally catch the elusive spectacled flowerpecker after a decade of only scattered sightings and photographs of the small gray birds.

The spectacled flowerpecker was first reported in 2009 and got its common name due to the distinctive white markings around its eyes that resemble a pair of eye glasses. Since scientists were unable to get their hands on the species, it hadn’t been rigorously studied or defined as a distinct species until the article published today in the journal Zootaxa.

A bird in the hand

Saucier and Milensky did not specifically set out to spot this bird or define a new species. This trip was the third to Sarawak in their collaboration with the Sarawak Forestry Corporation to document the diversity of birds of the island’s lowland forests. None of the spectacled flowerpecker sightings had ever been in the region or in Sarawak at all.

On a sunny morning last March, Saucier and Milensky set up a net on a ridge line above their field site to catch birds. As birds entered the net, the locals brought them down to the research site using cloth bags which encouraged more dormant behavior. That same day, a bag was carried down containing a surprise.

“I opened the bag, and I was like ‘Oh my God, this is the spectacled flowerpecker.’” Milensky says. “So, I immediately closed it back and showed it to Jacob.”

Saucier was also excited but took more time to absorb that such a windfall had fallen in their laps and that it really wasn’t just a rare coloration of a known species.

“I spent the rest of the day being like, ‘It can't be the spectacled flowerpecker — it could be this, could be that,’” Saucier says.

In fact, in his journal entry for the day, Saucier initially failed to mention the special bird.

“I was more concerned that there were roaches in my room, and then I remembered to put an asterisk later and wrote, ‘Oh, by the way, new species of flowerpecker in the net,’” Saucier says. “I think I didn’t include it because I wouldn't allow myself to believe at the time that this was a new species.”

It wasn’t until Saucier and Milensky started discussing how to reveal the discovery to their colleagues that it started feeling real to Saucier.

Interdisciplinary collaborations

Once back in the U.S., Saucier and Milensky focused on learning as much as possible from the specimen. As the only scientific representative of its species, the specimen got an in-depth examination. They studied its body structure and genetics in detail and collected as much as possible from the specimen. Fecal samples and stomach contents, for example, are valuable clues into things including the bird’s diet, associated bacteria and ecology.

Saucier and Milensky then collaborated with other experts to investigate the diverse data they collected. For instance, Smithsonian botanist Marcos Caraballo-Oritz – who studies mistletoe plants, including the dispersal of their seeds by birds – was invited into the research project. He helped identify seeds that were discovered in the specimen’s digestive tract and also contributed his expertise analyzing the evolutionary relationships of species.

Smithsonian geneticist Faridah Dahlan also joined the project to help with the genetic analysis. The analysis revealed the bird to be unique beyond the physical features Saucier and Milensky observed in the field. The analysis didn’t indicate any particularly close relative species with which it shares a recent ancestor, confirming the status as a distinct species. Scientists now have a new data point for analyzing the evolution and spread of flowerpecker species more generally.

What’s in a name?

In defining the species, the team also got to name it. They wanted the scientific name to emphasize the connection to the Borneo forests and honor the crucial role of the Dayaks – the region’s local indigenous people - in conserving Borneo’s ecosystems. They settled on Dicaeum dayakorum.

“We are very happy to be able to highlight the forests of Borneo and the people that live in and protect those forests,” Milensky says.

There is much still to be learned about the species, like how dependent it is on mistletoe, if it is migratory and what the effects of disturbing its habitat might be. But, formally describing the species encourages further research, provides a greater ability to effectively evaluate and respond to conservation needs in Borneo and highlights how much of the natural world remains to be discovered.

“I'm hoping this discovery may draw some attention to the fight to save these forests and the people who are there actively trying to do good conservation work in Borneo,” Saucier says.

Related stories:

Fish Detective Solves a Shocking Case of Mistaken Identity

This Smithsonian Scientist is on a Mission to Make Leeches Less Scary

Check Out Some of Our Most Popular Discoveries From 2018

Discovery and Danger: The Shocking Fishes of the Amazon’s Final Frontier