NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Six Bewitching Smithsonian Specimens to Get You Ready for Halloween

Check out some of the spookiest (read: coolest) items in the National Museum of Natural History’s collections.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Collage.png)

It’s that time of the year. Jack-o’-lanterns sit on porches everywhere, bats fly through the night and kids demand candy. People across the U.S. are clamoring for costumes and immersing themselves in all things spine-chilling.

At the National Museum of Natural History there are plenty of shocking (read: fascinating) specimens behind the scenes ready for Halloween. Here are some of the spookiest (read: coolest) items tucked away in the museum’s collections.

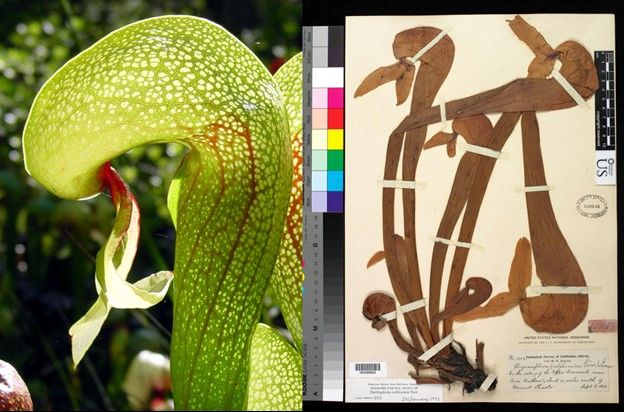

An insect-eating plant dressed up as a cobra

Kids aren’t the only ones putting on creepy costumes for the holiday. The carnivorous cobra lily is also ready to trick-or-treat. Though this plant wears its ensemble year-round, not just on October 31st.

The cobra lily (Darlingtonia californica) gets its name from the cobra-like appearance of its tubular leaves – replete with leaves that mimic a snake’s forked tongue or fangs. Rather than gulping down eggs as real cobras do or pulling nutrients from the soil like most plants, the cobra lily gets some of its nourishment by laying a trap for hungry insects.

Each cobra-shaped leaf has a hood that covers its opening, where nectar glands serve to lure unsuspecting insects attracted to the plant’s color and scent. Once an insect has taken the bait, short, stiff, backward-pointing hairs keep them trapped inside the pitcher. There they are confused by bright “windows” at the top of the plant -- which they mistake for exits -- before tiring and falling into the trap to dissolve into plant chow.

An accidental skeleton

Is it even Halloween without a cemetery? Especially one that turns up an unexpected skeleton.

In 1977, a group of workers uncovered a skeleton during a routine grave excavation at the Custer National Cemetery in Montana. But the bones didn’t belong to humans – they were fossilized remains of an ancient marine reptile.

The partial skeleton belonged to Dolichorhynchops osborni – a species of short-necked plesiosaur that lived between 220 and 60 million years ago. Six days of digging yielded the reptile’s entire pelvis, pectoral girdle and a near complete vertebral column.

Dolichorhynchops osborni was on display in the Smithsonian’s “Life in the Ancient Seas” exhibit from 1990 to 2013. Today, it is kept in collections at the National Museum of Natural History, where it is still mounted and provides convenient Halloween décor.

A mind-controlling parasite

Searching for a real-life zombie? Look no further than a parasite-controlled snail with translucent and colorful eye stalks that mimic caterpillars.

Leucochloridium paradoxum is a parasitic worm that amber snails ingest from bird poop. Once consumed, the parasite then proceeds to take control. Larva invade the snail’s eyes and transform them from slender stalks to throbbing caterpillar-like masses that will catch a bird’s attention for a meal. If eaten, the parasites develop into adults in the bird’s gut. There, they lay eggs that are released in the bird’s droppings.

But before it makes it into the bird’s stomach, Leucochloridium employs its powers of mind-control to ensure that the snail does what the parasite needs it to. Infected snails ditch their nocturnal ways and venture into broad daylight on the highest parts of plants – where they present an easy target for hungry birds.

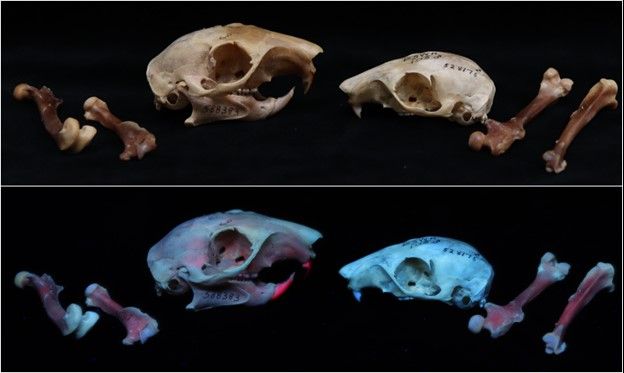

Glowing squirrel bones

While skulking around on Halloween night, keep an eye out for luminous jack-o’-lanterns, glowing ghosts and…fluorescent squirrel bones?

Nearly all fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) have a genetic condition called congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP). Squirrels with CEP have a mutation in a bit of their DNA that is important for making a key part of red blood cells. They make too much of a compound called uroporphyrin, which builds up in their bones, teeth and urine.

Uroporphyrin happens to fluoresce pink when exposed to UV light. So, under a blacklight, fox squirrel bones glow – unlike those from their close relative the eastern gray squirrel (S. carolinensis).

Other animals – including humans – get CEP too, which can cause skin blisters and sensitivity to light. Fox squirrels are spared from these unpleasant symptoms and don’t show signs of illness, though researchers aren’t sure why.

Peer into a crystal ball

Though some crystal balls are apt for fortune-telling, the Smithsonian’s orb is good for turning the room upside-down.

The museum’s sphere is the world’s largest flawless quartz ball – weighing in at 242,323 carats, or 106 pounds. No one knows where the quartz came from, though it was cut and polished in China in the 1920s. Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) and Madagascar are the best guesses, since these regions supplied the clearest quartz at that time. The sphere arrived at the Smithsonian shortly after it was made and has been on display ever since.

Why does this marvel of the Earth flip objects upside-down? It’s an optical effect due to the ball’s spherical shape, which makes it act as a lens. This crystal ball may not tell fortunes, but it certainly enchants visitors.

Insects that recycle corpses

Haunted houses bursting with corpses have nothing on the predatory bagworm (Perisceptis carnivora).

Bagworm larvae are known for their cocoons made from sticky silk and bits of plants fashioned into a “bag” where they transform into fuzzy moths. Perisceptis carnivora, however, has a different medium to attach to the silk: bodies of its prey.

These predatory caterpillars feast on ants, spiders, flies and a wide range of other insects. The larvae affix one end to a surface, such as a leaf, and deploy their free end to attack prey. After their meal, they stick what remains of their victims to a larval bag.

If that’s not disturbing enough, P. carnivora has an enemy of its own. Smithsonian scientists have reported parasitoid wasps – which lay their eggs in the bodies of other insects – emerging from these corpse-covered bags.

Related stories:

This Smithsonian Scientist is on a Mission to Make Leeches Less Scary

How Siobhan Starrs’ Harrowing Hike Shaped the New Fossil Hall

Check Out These Unexpected Connections in Natural and Presidential History