NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

How Seven of Nature’s Coolest Species Weather the Cold

Check out these unexpected adaptations to extreme cold.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/A_yellow_flower_covered_in_snow..jpg)

You’ve probably heard of hibernation and seen the thick fur coats that help some animals stay warm in winter, but organisms around the world have many other ways of surviving freezing temperatures — from blood with antifreeze to abnormally resilient brains. Here are seven unexpected adaptations to extreme cold.

Flowers that produce heat

Eastern skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) gets its name from the stinky odor that wafts from its blossoms as it generates its own heat. Found in eastern North America, the plant warms its flowers for weeks at a time and can even melt snow. As the temperature drops, skunk cabbages move starches from storage in underground stems to their flowers, where they burn the starches to produce heat — similar to the way mammals burn fat. This warmth, along with their pungent smell, attracts insects that pollinate the plant in early spring.

Plants with fuzzy coats

Other plants opt for wooly winter coats to stay warm. High on the Tibetan Plateau, a group of plants in the sunflower family known as Sausurrea start to resemble festive snowballs in winter months. The white, hair-like fibers, called pubescence, insulate the plants from low temperatures, ward off hungry herbivores and might even act as refuges for pollinators during bouts of bad weather.

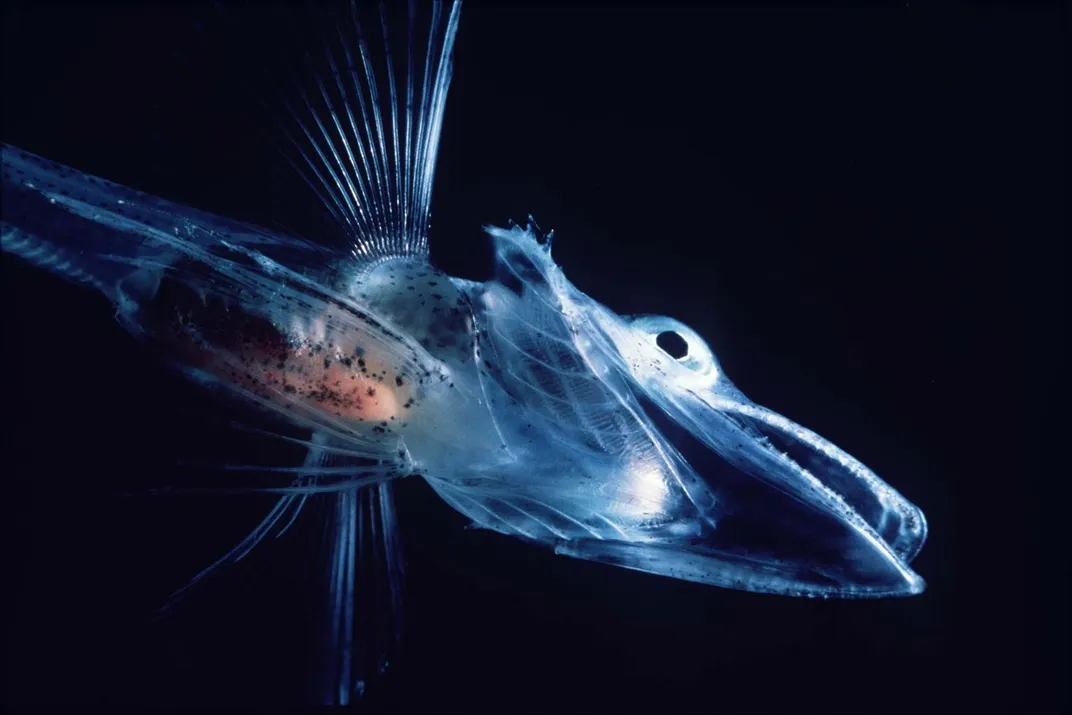

Fish with antifreeze

The seas around Antarctica can dip below 32 degrees Fahrenheit and remain liquid thanks to the salt in the water. Antarctic icefish (Channichthyidae) use a different strategy to keep from freezing solid. Antifreeze proteins circulate through their blood and bodies and bind to ice crystals to stop further growth. Studying these proteins is helping scientists find ways to store and transport donor organs more efficiently.

Beetles with a sweet trick

Since first discovering antifreeze proteins in icefish, scientists have found similar molecules in cold-adapted organisms around the world. Most of these natural antifreezes are proteins that flow through the blood and gut and bind to tiny, existing ice crystals. But the Alaskan Upis beetle (Uris ceramboides) uses a different strategy. It incorporates a sugar-based antifreeze directly onto the membranes of its cells to keep ice crystals out and prevent the formation of ice inside the cells. This allows the beetles to survive in temperatures lower than -70 degrees Fahrenheit.

Squirrels with brains that reset

Arctic ground squirrels (Urocitellus parryii) manage to stay alive during freezing winter months, but just barely. These fuzzy mammals exhibit the most extreme example of hibernation, with core body temperatures plummeting below freezing for weeks at a time. Long periods of extreme cold cause connections between brain cells to wither. But within just a few hours of waking from their hibernation, the squirrels’ exceptionally resilient brains bloom back to life — restoring and even building new neural connections.

Marine invertebrates with big plans

Some species don’t just survive the cold — they thrive in it. Marine invertebrates in polar regions have slow metabolisms and don’t need much oxygen for their cells to function. But colder water stores more oxygen than usual. This surplus of oxygen allows marine animals such as sea spiders and sponges in Antarctica to grow abnormally large, in a phenomenon called polar gigantism. This growth can also happen in frigid deep water, where the process is called deep-sea gigantism.

Mammals that shake things up

Humans also have adaptations that help us brave the cold. Shivering warms us up by using muscles to burn brown fat cells. When we shiver, our muscles release the hormone irisin. This hormone, which muscles also release during exercise, converts white fat to brown fat, which is more readily burned. Burning brown fat cells creates heat and helps us maintain our body temperatures in cold environments.

While the ability to shiver evolved in all people, some populations have additional traits that help them in chilly weather. Large nasal cavities warm and moisten air by swirling it around before it reaches the sensitive airways and lungs. This helps prevent irritation and damage in cold, dry environments. Neanderthals — the most cold-adapted species in our evolutionary history — had huge, broad noses that helped with this. A different solution evolved in some modern humans. Instead of becoming broader, the noses of some human populations from colder climates evolved longer, narrower nostrils. The more you nose!

Related Stories:

Five Reasons to Love Bats

Five of Nature’s Best Beards for World Beard Day

Six Avatar-Themed Items in the Smithsonian Collections

Five Species to Wrap Up Invasive Species Week