NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

10 Popular Scientific Discoveries from 2020

Here are some of 2020’s most popular discoveries involving scientists from the National Museum of Natural History.

:focal(497x357:498x358)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/A_black_and_white_spotted_bird_walking_on_the_ground..jpg)

This year was one of the strangest in recent history. But through all of the challenges of 2020, scientists at the Smithsonian and around the world continued to unravel the mysteries of our planet and the life it supports. From inky deep sea fish to velcro-like feathers, here are some of 2020’s most popular discoveries involving scientists from the National Museum of Natural History.

There is hope for a sustainable ocean

Communities around the world depend on oceans for food and income, but harvesting, climate change and pollution threaten marine ecosystems and species with extinction.

A large group of scientists including the Smithsonian’s Nancy Knowlton compiled case studies about how ocean environments and populations have rebounded and responded to changes in human activity over the past few decades. They concluded that it is possible to sustainably rebuild ocean populations within the next 30 years if the necessary actions are implemented and made a priority at local and international scales. In their Nature paper, the group also provided a roadmap for what these actions might look like, breaking them into categories such as protecting and restoring habitats, adopting sustainable fishing measures, reducing pollution and mitigating climate change.

After dogs diverged from wolves, they stuck by our sides

While some researchers planned for the future, others looked to the past. The Smithsonian’s Audrey Lin and an international team of researchers sequenced ancient genomes of 27 dogs from up to 10.9 thousand years ago to learn about the pup-ulation history of our furry companions.

In a Science paper, the team makes the case that dogs all have one common ancestor without much genetic influence from wolves after the initial domestication. By analyzing the dog genomes alongside human genomes from similar time periods and locations, the researchers also found that the migrations of some dogs matched those of humans. DNA helps researchers track the movements of populations over time, but the geographical origins of dogs remains unknown.

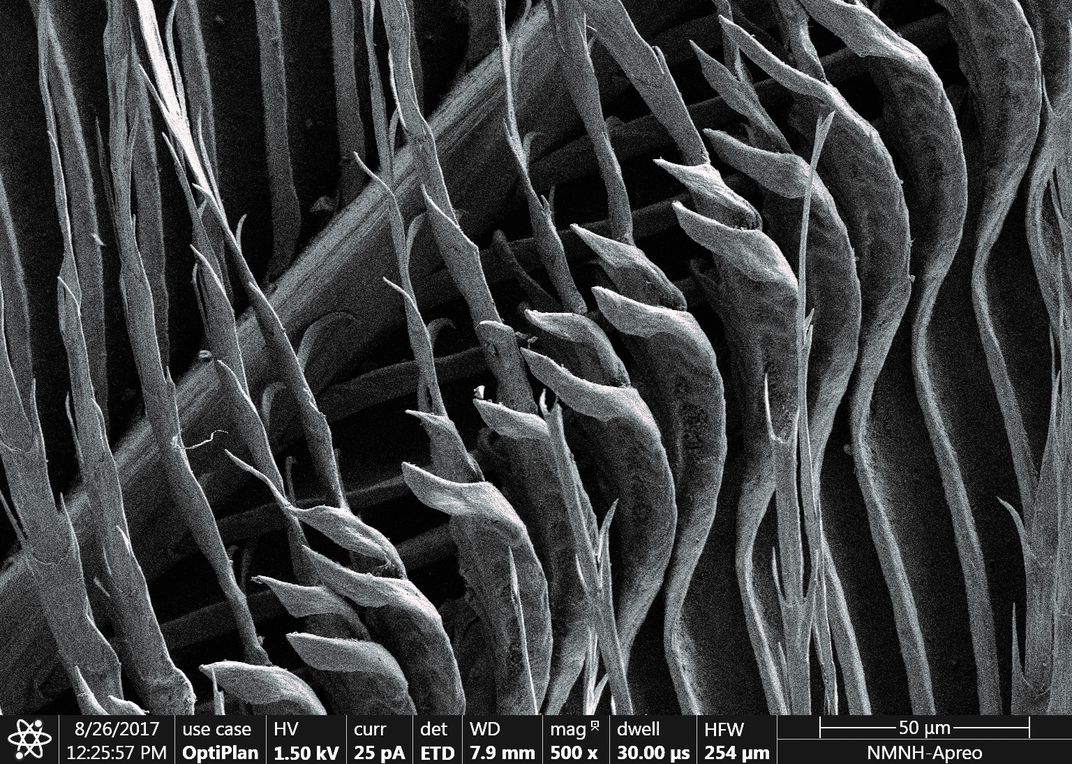

The skin of deep sea fish might be the blackest material in nature

On the opposite end of the spectrum from domestication, fish in the deep sea have evolved camouflage to hide themselves from predators in the pitch black water.

To avoid detection in the light that bioluminescent organisms use to hunt, certain fish have evolved skin that absorbs more than 99.5% of light. Smithsonian Invertebrate Zoologist Karen Osborn and her team discovered a unique arrangement of the pigment cells in these ultra-black fish. The finding, which the team published in Current Biology, could help engineers design light, flexible ultra-black materials for use in telescopes, cameras, camouflage and other optical technology.

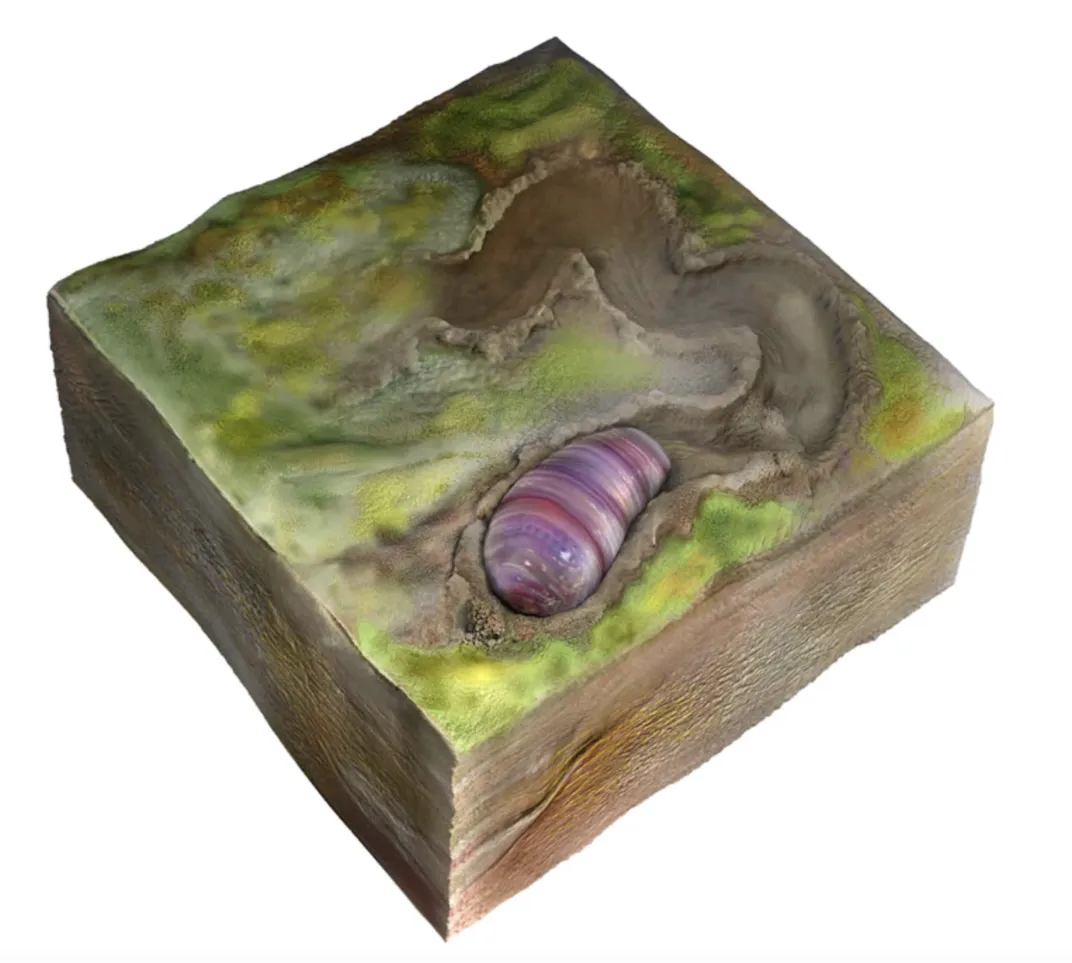

Scientists find the earliest known organism with bilateral symmetry

As life evolved from single-celled organisms into complex forms, different ways to organize a body arose. Humans and most other animals have bilateral symmetry, in which sides of the body are mirrored across a single vertical plane.

This year, Smithsonian postdoctoral fellow Scott Evans and a team of researchers described the earliest known bilaterian in a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper. Found fossilized in South Australia, the worm-like Ikaria wariootia had a simple, small body plan and likely created sediment tunnels, which became trace fossils. The discovery provides a link between a group of fossils from more than 550 million years ago and life today.

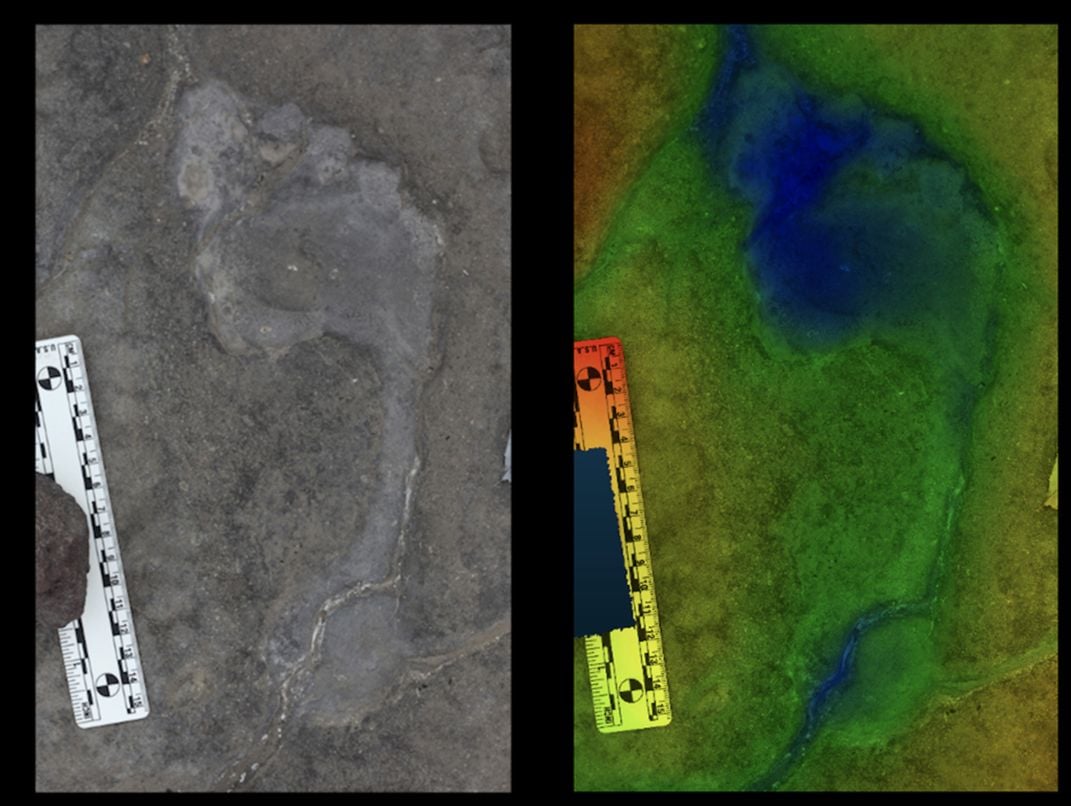

Ancient footprints help researchers step into life 11,000 years ago

Just as some scientists study the sediment tunnels of ancient organisms, others use fossilized footprints to learn about more recent ancestors.

Smithsonian researchers Briana Pobiner, Adam Metallo and Vince Rossi joined colleagues to excavate and analyze more than 400 human footprints from the Late Pleistocene — around 11,000 years ago — in Engare Sero, Tanzania. These footprints provide a snapshot that reveals information about body size, walking and running speeds and group dynamics of the people that left them. They published their findings in a Scientific Reports paper.

Velcro-like latching in feathers improves flight

Anthropologists weren’t the only ones studying locomotion this year. Avian researchers also rose to the challenge.

When birds fly, the variable overlap of their feathers allows them to change the shape of their wings during flight. These morphing wings give them exceptional control. New research published in Science by Smithsonian Research Associate Teresa Feo and colleagues from Stanford University shows how a one-directional, velcro-like mechanism helps feathers stay in place and prevents gaps. The team created and flew a feathered biohybrid robot to show how the mechanism assists flight. The findings could help engineers improve aircrafts.

Researchers sequence hundreds of bird genomes

Birds are quickly becoming one of the best-studied groups of organisms in the world.

As part of a larger effort to sequence the genomes of all living bird species, several Smithsonian scientists joined researchers from around the world in collecting and sequencing the genomes of 363 species. The DNA sequences, published in Nature represent 92.4% of bird families and include 267 newly sequenced genomes. Researchers expect the DNA of so many species to reveal new information about bird evolution and help with conservation efforts, such as bringing endangered species back from the brink of extinction.

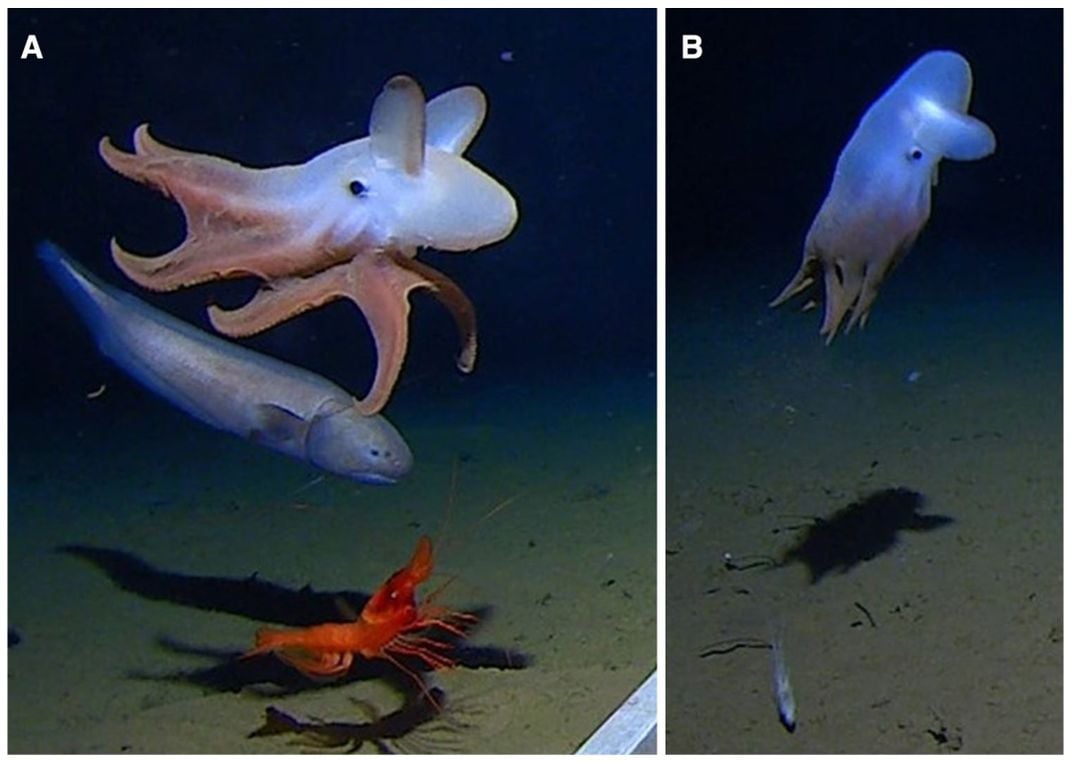

Scientists film the deepest cephalopod ever recorded

While scientists will soon have the DNA of thousands of bird species at their fingertips, organisms of the deep sea are still poorly known.

In a Marine Biology paper earlier this year, NOAA scientist and Smithsonian curator of cephalopods Michael Vecchione and his colleague Alan Jamieson from Newcastle University in the UK recorded a dumbo octopod (Grimpoteuthis sp) at two record-breaking depths of 18,898 feet and 22,823 feet in a trench of the Indian Ocean. The videos are the deepest reliable records of any cephalopod — a class of marine animals including squids, octopods, cuttlefishes and nautiluses — ever recorded. The footage is the first to show a cephalopod in an ocean trench and extended their known depth range by almost 6,000 feet.

Tuatara genome solves evolutionary mysteries

The tuatara is the only living member of the reptilian order Rhynchocephalia (Sphenodontia), which diverged from the lineage of snakes and lizards about 250 million years ago.

A team of researchers, including the Smithsonian’s Ryan Schott, Daniel Mulcahy and Vanessa Gonzalez, partnered with other scientists around the world to sequence and analyze the unusually large genome of this New Zealand species. By comparing its genome to the DNA of 27 other vertebrates, the scientists provide insights into the evolution of modern birds, reptiles and mammals. Their results, published in the journal Nature, also help solve persistent questions about the species’ place and timing on the evolutionary tree and provide population data that could bolster species conservation efforts. The group worked with the Māori tribe Ngātiwai to design and carry out the study, and the paper’s authors provided a template for future partnerships between researchers and indigenous communities.

Upside-down jellyfish can sting without contact through mucus

You don’t have to touch a Cassiopea xamachana — an upside-down jellyfish — to get stung. Just swimming near them is often enough.

A research team led by Smithsonian scientists took a closer look at this phenomenon, known as stinging water. The jellyfish, they discovered, expel a mucus that contains spinning balls of stinging cells. They named the blobs of cells cassiosomes in their Communications Biology paper.

Let’s hope 2021 has less of a sting.

Related Stories:

Landmark Study Shares Smithsonian Bird DNA Collected Over Three Decades

These are the Decade’s Biggest Discoveries in Human Evolution

Rare Iridescent Snake Discovered in Vietnam

Get to Know the Scientist Discovering Deep-Sea Squids

10 Popular Scientific Discoveries from 2019