NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

The Secret Lives of Mosquitoes, the World’s Most Hated Insects

While some are a nuisance, others working as nighttime pollinators may be critically important to a functioning ecosystem

:focal(550x367:551x368)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/A_mosquito_on_a_white_and_yellow_flower.jpg)

In the forests of the Eastern U.S. lurks a mosquito so large, it dwarfs nearly all of its 3,570 relatives. Buzzing through the trees during the day, her long legs trail beneath her as she sniffs out her next meal. When her antennae sense and lock onto her target, the monstrous mosquito extends her long, curved proboscis and inserts it into the soft center of a flower to slurp up the sweet nectar.

That’s right — this mosquito doesn’t drink human blood, and neither do many of the other species we are so quick to swat.

Thanks to its plant-based diet, this hefty insect — fittingly known as the elephant mosquito — has generally flown below our radar. Instead, we have long concerned ourselves with the three percent of mosquito species that infect us with zoonotic diseases like malaria, dengue fever and Zika virus. Make no mistake: our irritation with these insects is warranted. For humans, mosquitoes are the deadliest animals on Earth. But the long-legged, sugar-sipping elephant mosquito is one of many species that might be doing more good for humanity than bad.

Aside from the 100 or so species that commonly spread disease to humans, there are thousands more with fascinating behaviors and gorgeous bodies that we barely understand, yet we still call for their indiscriminate eradication. Must we also evict the magnificently iridescent mosquitoes whose larvae prey on dangerous species, or the ones that pollinate flowers at night, or the single species known to risk its life to protect its eggs from harm?

“We have been grossly underestimating the diversity of mosquitoes,” said Yvonne-Marie Linton, curator of the Smithsonian's National Mosquito Collection and research director at the Department of Defense’s Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit (WBRU). “The number of new species that we find everywhere we go is phenomenal.”

With the help of the largest mosquito collection on the planet, Linton recently released “Mosquitoes of the World” with her co-authors Richard Wilkerson and the late Daniel Strickman. The 1,300-page compendium highlights the diversity and importance of all mosquitoes, not only those feared by humans. Through this massive endeavor to expand our knowledge of mosquitoes, Linton’s team has uncovered the unexpected beauty, benefits and diversity of the world’s most hated insect.

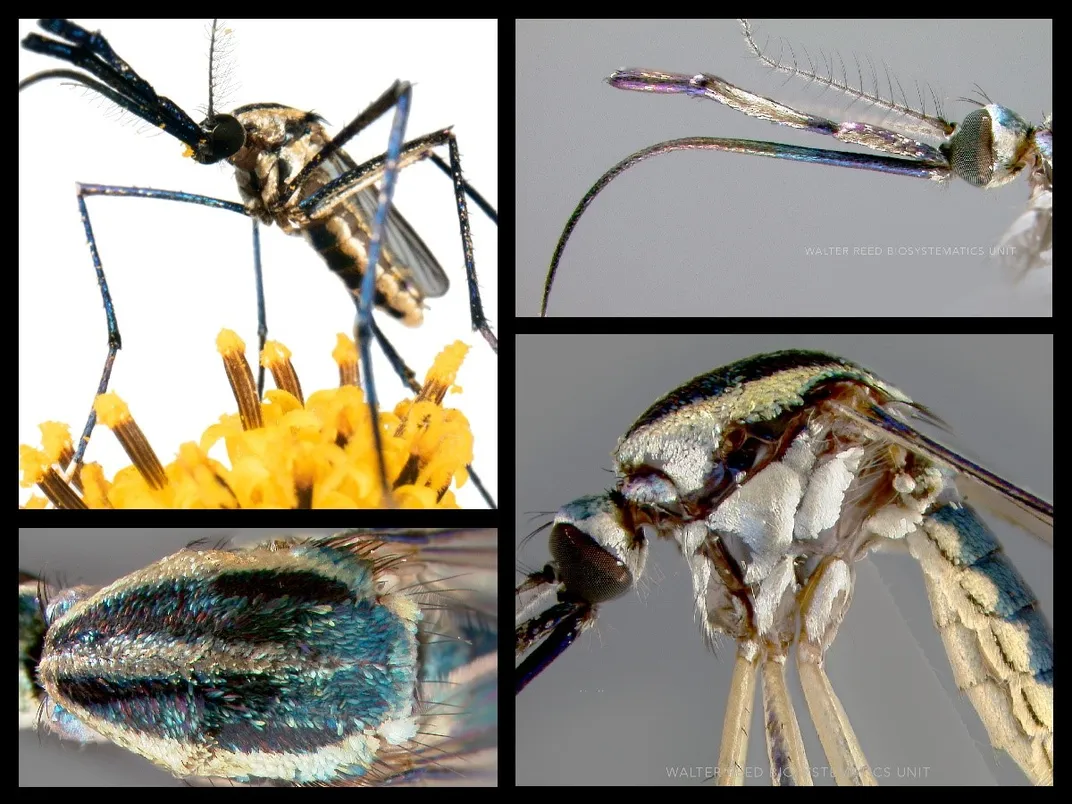

Dressed to impress

As the elephant mosquito buzzes from flower to flower, its sapphire-blue and silver-striped body glints in the sunlight. Brilliant scales along its back and legs reflect the diverse palette of colors mosquitoes have evolved to wear. Some species match hues to blend in with their surroundings while others stand out in shimmering style. Their plumages range from iridescent violets and golden greens to brilliant matte orange and black and white polka dots. Many others, like tiger mosquitoes, don prison stripes which are thought to confuse predators and hosts by making it harder to visually lock on to their form.

Aside from the Asian tiger mosquito, a well-known carrier of at least 25 pathogens, Linton calls most of the dangerous species “brown blobs.”

“The mosquitoes that cause so many problems for humans are usually the boring-colored ones," she said. As curator of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s 1.7 million mosquito specimens, Linton has spent years contributing to the WRBU’s online mosquito database, entering descriptions, disease associations and genetic identifiers for all known mosquito species.

Scattered among the brown blobs are dozens of mosquitoes which have earned far more colorful descriptions from Linton. For example, she’s branded mosquitoes in the genus Sabethes as the “Hollywood showgirls of the mosquito world.”

One especially fabulous species, Sabethes cyaneus, is wrapped in violets and blues from head to toe. Both males and females possess elongated, feather-like scales on their second pair of legs, a look reminiscent of the fringed boots worn by the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders. Upon their discovery, the purpose of these adornments perplexed researchers.

“There was just no immediate rationale as to why they would have these leg paddles,” said Linton. “These mosquitoes fly in tropical jungles and these paddles are not very aerodynamic — it didn’t seem to be an advantage.”

But in 1990, scientists shaved the legs of these mosquitoes and discovered that fringe plays a critical role in mate recognition. The females couldn’t care less about the presence or absence of the paddles on males, but when females lacked their fluffy legwarmers, the males refused to mate with them. Mosquito matchmaking, it seemed, was more complex than previously thought.

Looking for love

Mosquitoes are pretty good at proliferating when the weather is right. Anyone who’s visited Alaska in the summertime can attest to that. You wouldn’t expect the mosquito mating process to be particularly involved — and truthfully, most species are quick and dirty about it. But there are some exceptional species out there with dances, displays and positions worthy of a good romance novel.

While the high-pitched hum of a mosquito’s wings induces anxiety in most of us, it’s all love songs for elephant mosquitoes. Males and females are known to perfectly synchronize the tone of their buzzing within a matter of seconds by matching the frequency of their prospective mate’s wing beats. It’s thought that harmonized flying frequencies makes mating in mid-air easier, though more research is needed to be certain.

For S. cyaneus, a mate’s musical skills don’t matter as long as they can dance. When these insects decide to get down to business, they engage in a courtship as elaborate as their feathery physiques — and they almost always do it hanging upside-down.

Perched on the underside of a twig, a male begins by waving his feathered legs overhead at a nearby female. If she doesn’t fly off or kick him away with her hind legs, he waves a little faster, then flexes his standing legs and flicks his proboscis a few times

If dangling and dancing isn’t interesting enough, there are also male mosquitoes with enormous fluffy antennae for sniffing out far away females while others form dense swarms and mate as they fall through the air. And in a strangely Lolita-esque style, males of the New Zealand genus Opifex are known to patrol water pools, guarding and attending to growing pupae. They wait to impregnate the adult females as soon as, or even before, they completely emerge from their casing. “Those ones are like the sexual predators of the mosquito world,” said Linton.

Miniature helicopter moms

In forests, holes in tree trunks are a reliable water source for growing mosquito larvae year after year, but mosquitoes will deposit their broods in just about any pool of water they can find. Their eggs can be found in crab holes, bamboo nodes and in rainwater welled in the ridges of palm fronds, fruit husks and curled leaves on the forest floor. Anopheles gambiae, the major vector of malaria in Africa, often chooses muddy hoof prints.

When a female elephant mosquito is ready to lay her eggs, she will seek out a tree hole to deposit her clutch. In a style bound to make human mothers cringe, she deposits her eggs in mid-air by flinging them from her abdomen, one-by-one, into the water while she hovers outside the hole. This egg-catapulting behavior may serve to protect her from predators or any catty, dive-bombing mosquito moms that have already laid claim to the pool.

Once she has tossed her eggs, our mama mosquito flies off with nary a thought for the future of her young. This behavior is hardly unique — maternal care among mosquitoes is virtually unheard of. But there is at least one mosquito mom that breaks the mold: The hairy-lipped mosquito, Trichoprosopon digitatum.

Floating on rainwater cupped by fruit husks left behind by monkeys, hairy-lipped mosquito eggs are “susceptible to being splashed onto the ground by a raindrop, or carried away if the husk overflows,” said Lary Reeves, an entomologist at the University of Florida who studies mosquito ecology. Reeves, who has studied T. digitatum in the Brazilian rain forest, said the mother mosquito braces herself above her brood and guards them fearlessly until they hatch, edging them away from incoming insects, water and debris.

“We went to collect adults of this species in Brazil and this mosquito did not want to leave its eggs,” he recalled. “It could have easily tried to save itself by flying away, but instead it just stayed there, trying to hold on as tightly as it could.”

Reeves said it’s tough to characterize this behavior without anthropomorphizing — assigning human-like qualities to — the mosquitoes. But he agrees egg-guarding “does give the impression that this mosquito is aware of the potential danger that's there for its young.”

While T. digitatum is likely acting out of pure instinct to procreate rather than tender motherly love, maternal care is a rare trait among mosquitoes and other flies. “Nothing surprises me anymore about the complexity of mosquito behaviors,” said Reeves. “They do a lot of weird and wild things.”

Feeding for a cause

When the eggs of an elephant mosquito hatch, they can grow far larger than most mosquito larvae, nearly the thickness of a pencil. Most larvae filter-feed the water for algae, detritus and other microorganisms. But elephant mosquito larvae are spiny, insatiable hunters. Fortunately for us, they readily munch on the wriggling young of other mosquitoes. This predatory nature has not gone unnoticed; elephant mosquitoes have been deployed as a bio-control method for disease vector mosquitoes in places like Texas, Vietnam, Uganda and Samoa.

“People have taken the most ferocious larval feeders and put them in rice fields to eliminate mosquitoes that bite humans,” said Linton. “They’re just massive, they decimate everything. One elephant mosquito larvae can eat 30 to 40 of the piddly little ones every day.” Their hearty diet as youngsters provides enough protein to last their entire adult life, so they have no need for a blood meal to lay healthy eggs.

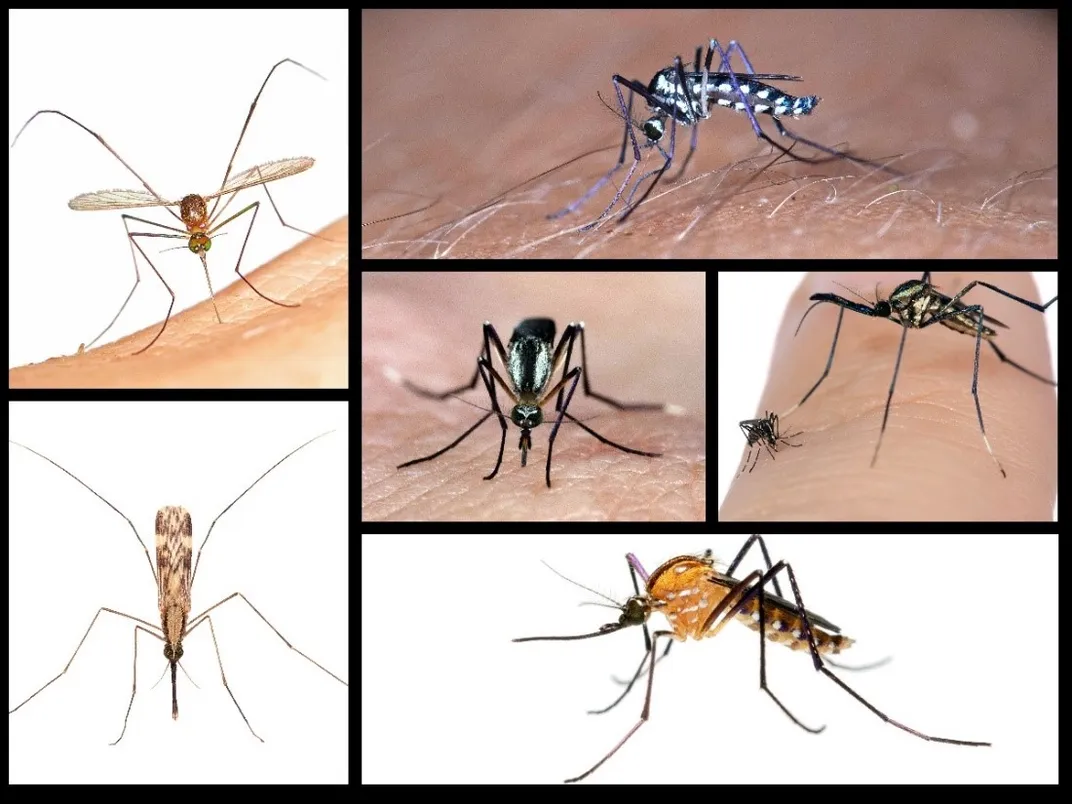

There are dozens of species that, like the elephant mosquito and its close relatives, never drink blood as adults. But to tell the truth, most of them do. Humans aren’t always on the menu, though. Hematophagus, or blood-sucking, mosquitoes also feast on frogs, crocodiles, earthworms, armadillos, manatees and even mudskipper fish.

Recent research on fossilized mosquitoes suggests these insects were originally reptile feeders, sucking the cold blood of dinosaurs, Linton said. “In a lot of cases we're not their preferred host at all. We just happen to be there.” By our own nature, we also out-compete, over-harvest and crowd out lots of the animals that mosquitoes rely on, giving them no choice but to suck our blood instead.

When they’re not sucking blood for protein, mosquitoes get their energy from nectar, sap and fruit juice. Mosquitoes in the genus Malaya, however, poach their sugars from other insects. Using their antennae and short proboscis, they will stroke the faces of ants and aphids, causing them to regurgitate a sweet liquid called honeydew from their mouths.

“We don't know if these mosquitoes are mimicking hungry ants and ‘asking’ them for honeydew, or if they are accosting the ant and the ant’s defense is just giving it up,” said Reeves.

What we do know is that all mosquitoes rely on sugary plant liquids for most of their diet, and this tight relationship with plants could be far more important than we realize.

Working the night shift

Overshadowed by their vampiric tendencies, mosquitoes’ pollination duties are highly understudied. “There's a big bias, just because fewer people are looking at flowers after dark,” said Reeves. “I don't know that I've ever seen a mosquito at a flower during the day, but I've seen thousands on flowers at night.”

Mosquitoes are known pollinators, but which plants they visit and how effectively they disperse pollen relative to bees, butterflies and beetles is poorly understood. Studies have shown through flower-blocking experiments that when night-time pollinators are excluded, some flowers are less successful, that is, they tend to produce fewer viable seeds compared to flowers whose day-time pollinators are blocked out.

This, along with the sheer magnitude of mosquitoes found on flowers at night, suggests that nocturnal creatures like mosquitoes may be just as important for ecosystem functioning as the familiar pollinators we see during the day. Mosquitoes have a long way to go in terms of recognition, though. Even in the scientific community, they’re often excluded from pollinator studies. “Few people, even among entomologists, expect to see mosquitoes on flowers,” said Reeves.

With their proboscises in every ecological pie, mosquitoes are intricately intertwined with countless plants, animals, microorganisms and pathogens, yet our perception of them remains narrowly focused on the itchy welts they leave and diseases they carry. If their enormous impact on humans alone is any indication of their relationships with other species, it would behoove us to focus more effort on understanding them in the context of their environments.

“We have so much more to learn,” said Linton. "People often assume we’ve figured mosquitoes out by now, but we are far from done.”

Indeed, the lesser-known mosquitoes out there — with their fancy colors, strange sex lives and variety of hosts — reflect a rich diversity that’s hard to ignore once you take a closer look. Chances are there's more than a few out there that could save lives, if only we could appreciate theirs.

Related stories:

Get to Know the Scientist in Charge of Smithsonian’s 1.9 Million Mosquitoes

How Museum Collections Advance Knowledge of Human Health

Eight of Nature’s Wildest Mating Rituals

Five Species to Wrap Up Invasive Species Week