NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Honoring the Overlooked Contributions of Women Anthropologists in the National Anthropological Archives

Ongoing research in the Department of Anthropology brings to light historically under recognized contributions of female researchers and staff

:focal(1500x1200:1501x1201)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ac/6d/ac6ddfb8-902d-40f5-b7d0-af4a607113b4/joanna_scherer_margaret_blaker_rebecca_chancey_demallie_anthro_castle.jpeg)

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History has always been enriched by remarkable female researchers whose contributions have changed the world of science and added to the world’s largest collections of natural specimens and cultural materials. The crucial legacy of these researchers extends all the way from pioneering curators like marine biologist Marian Pettibone and anthropologist Adrienne Kaeppler to current museum leaders, like chief scientist Rebecca Johnson and the repatriation program manager, Dorothy Lippert.

However, not all women in the museum’s past were appropriately recognized for their accomplishments and dedication. Over the decades, much of their work has gone largely unacknowledged. This includes the work of a team of women who helped shape what is now the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives (NAA) and Human Studies and Film Archives into an unparalleled repository documenting the world’s people, languages and cultures.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2e/85/2e85f2b4-484a-44b8-8c35-8ff29ad9b5f2/51041813_2162013983856892_1772156424621654016_n.jpg)

These early researchers had their work cut out for them. When the NAA was first established in the late nineteenth century as the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE), it was tasked with maintaining a sprawling repository of field notes, recordings and manuscripts created by anthropologists as they conducted research.

While much of the BAE’s work revolved around documenting Native American languages and culture, practices employed by early anthropologists often overlooked the contributions of Indigenous collaborators. Although some Indigenous anthropologists worked with the BAE from the beginning, such as Francis la Flesche, the first professional Native American ethnologist, the stories and accomplishments of many Indigenous researchers at the time were obscured by the work of their colleagues.

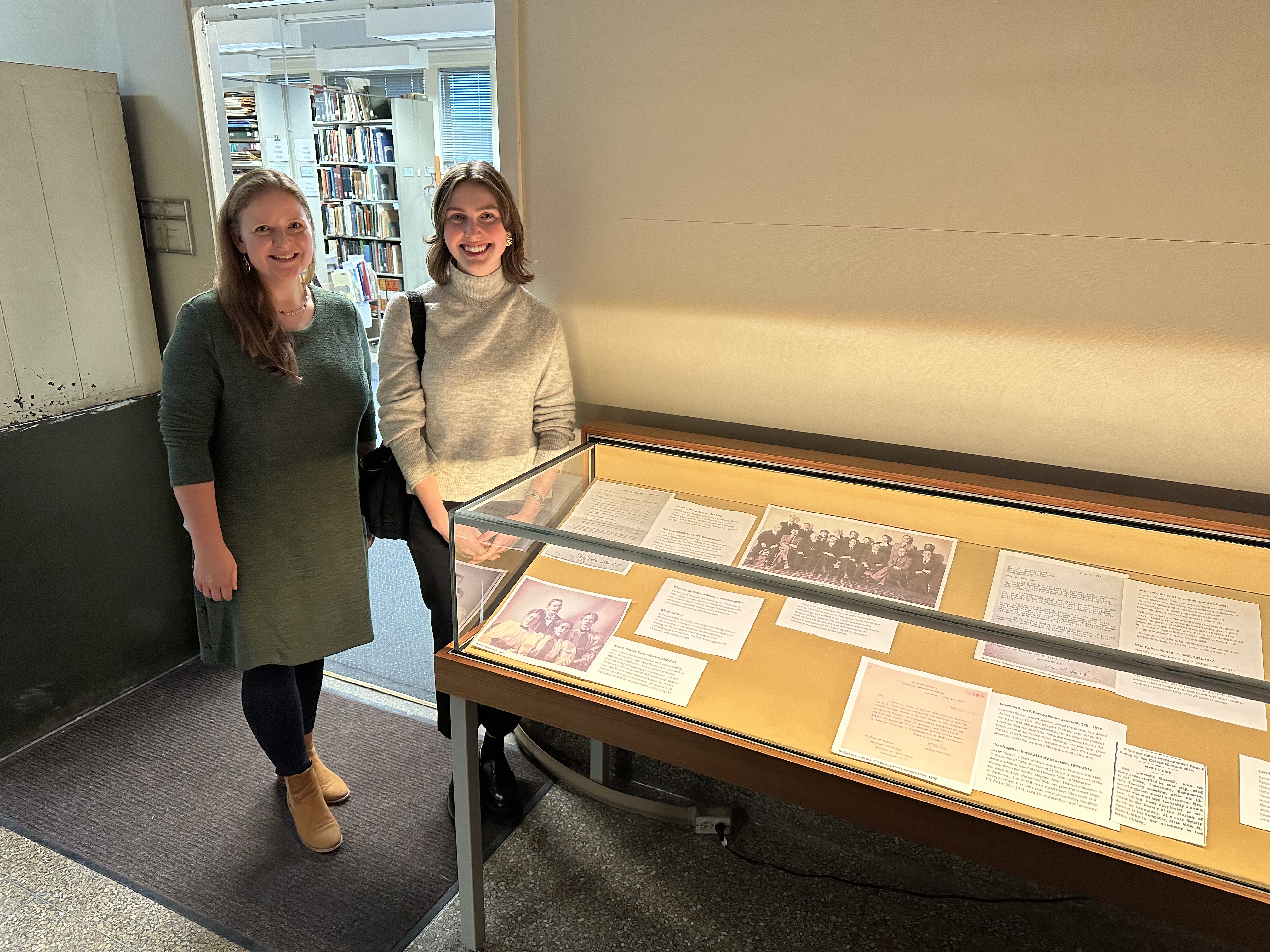

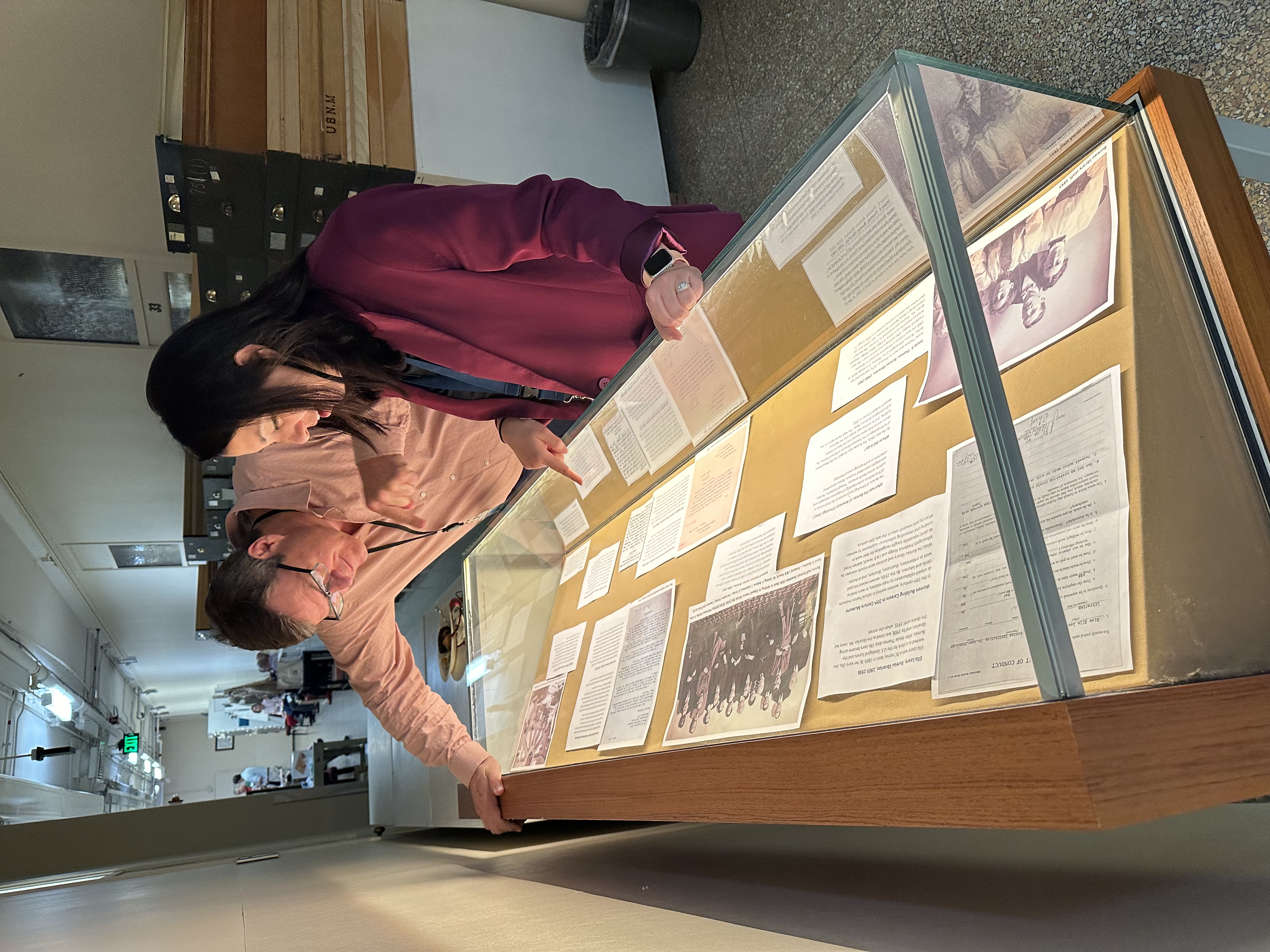

Women are another group whose contributions to the archive were often overlooked. To help shed light on how these women researchers helped set the foundation for the BAE, supervisory anthropologist Celia Emmelhainz recently teamed up with interns Mary Margaret Lea and Leah Ollie to comb through the historical record to highlight these stories of women in the archives and the department. This included sifting through archival materials, employment records and oral histories.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/23/d123f8ed-55dd-4d85-905f-abb81808b937/262929106_4720184408039824_6966758664092850790_n.jpg)

All of this research paid off. The team recently revealed the significant contributions of both paid and unpaid women who provided crucial labor that helped make the museum’s anthropology department what it is today.

Ollie and Lea came to the museum as a part of the Because of Herstory Women’s History Internship cohort that is tasked with amplifying the historical work of women across the Smithsonian. Both interns started out with a long list of records in the anthropology department. As they worked their way through, they tried to fill in as much information as they could about each woman they came across.

This undertaking proved difficult — women’s work was often buried beneath a man’s name. “In science and natural history museums across the world, especially during the 19th century, women often weren’t formally employed — they would volunteer or they would work on projects with their husband or father,” Emmelhainz said. “They were sometimes listed as stenographers or clerks, but would also be doing additional work.” Women were sometimes not credited at all because they were not formal researchers or worked as assistants to men.

To help fill in these gaps in the record, Lea interviewed past and current employees about their own memories of who worked in the department and what they did. Ollie leveraged her background in journalism and communications to develop social media posts to educate the public about women in the department. By the time the internship ended, both interns walked away with valuable research experience and a deeper understanding of how women have always been essential to the museum’s work.

“So much of what we discovered about these women was that there were a lot of relationship networks in the department that kept their work alive,” said Lea, a senior at the University of Virginia. “It was often women acknowledging each other in their footnotes, or having these informal networks of expertise that really helped get their work noticed.”

Despite being a straightforward mission, it was no small feat to bring the work of women in the department to light. While a given paper may have a male curator’s or chair’s name on the front, Emmelhainz and her team found that the acknowledgments section often included the names of women and detailed descriptions of their valuable contributions. Processing and digitizing these documents gets women’s names into the archival record, where they can be used to create finding aids and can be properly credited.

While identifying the hidden research contributions of women in the department was an important part of the project, the team also made sure to extend the same care and attention to women who worked in other roles, like archivists and librarians. Their efforts to keep the day-to-day operations of the department running smoothly ensured anthropologists could do their work.

“It’s really important to us to balance the stories of women in the archive and also the women who maintained and performed the labor over the years in the archives in order to conserve the history of this work,” said Ollie, a junior at Butler University.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/43/c3/43c3670c-f23e-4218-839d-ca16b6540641/2023-07-12_mml_and_lo_in_sia_reading_room.jpg)

During the project, the team came across several individuals who stood out. Many women who were initially classified as aides, assistants or volunteers were eventually advanced to the level of librarians and archivists, such as Mae W. Tucker, who worked for the BAE from 1925 to 1952. The team uncovered a 1947 letter she wrote pushing to be reclassified as an archivist from a clerk based on her work in the archive. After archaeologist Frank H. Roberts also pushed for her reclassification in 1948, Tucker was given a promotion to archivist and a pay increase in 1949, more than a decade after she took over leadership duties in the archive in 1937.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dc/a8/dca82890-9269-4c05-a375-65fc1b40e7b3/1947-06_mwt_archivist.jpeg)

This work also led to the rediscovery of a mother-daughter duo, Louvenia Russell and Ella Slaughter, who worked in the BAE at the turn of the century. In reviewing historical records, Deborah Shapiro, a reference archivist at the Smithsonian Institution Archives recognized that as Black women, they were classified as laborers and received some of the lowest salaries at the Bureau despite their additional work as library assistants. Louvenia retired in 1899 without being recognized for her contributions to the library by the Bureau, and Ella took her place. Ella’s library work was eventually recognized in a 1904 Bureau report.

“Women also do administrative labor, they do support labor. And that labor has value for a science museum,” Emmelhainz said. “So we don’t want to just reclass everyone as a researcher in our minds, we want to recognize that all of these forms of labor need to be recognized.”

Over the course of this project, Emmelhainz, Lea and Ollie did notice some echoes of similarity between their own work and the work of the women they were trying to bring to light. Women are often the ones who do this extra labor to make sure women’s history is preserved in the first place. This adds additional career responsibilities that many of their male colleagues may not worry about.

However, Emmelhainz and the rest of the anthropology department made sure to recognize the interns’ work as important contributions to expanding the history archive. As such, both Lea and Ollie will always be credited for the labor and care they put into their efforts. According to Ollie, “that was something that Celia really helped us talk through in terms of understanding not only our own role in doing this significant work to credit these women, but also making sure we knew how we would be credited in the future for doing this work.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/88/98/88983df0-dcb3-44d1-a85e-b4bd4135ed96/screen_shot_2024-03-13_at_121710_pm.png)

The team thinks that uncovering the historic roles of women at the Smithsonian is the first step in a larger effort to make sure women are recognized for their research and work. As more of these stories come to light, Emmelhainz hopes they will become easily accessible to people online who do not have the access or time to sift through the historical archives.

“To do that, we have to have as many published sources as possible that attest to the value of these researchers,” Emmelhainz said. “To me, that spoke to the tremendous value of getting these women’s stories out in writing, because with that, we can start to build the case for their lasting impact on science.”

Related Stories

Meet the Archaeologist Leading the Museum’s Repatriation Efforts

How Film Helps Preserve the World’s Diversity

How Arctic Anthropologists are Expanding Narratives about the North

How 3D Worms Provide a Peek Into Historic Smithsonian Collection