NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

The Name Game: A ‘Celebrity’ Cephalopod Specimen Correctly Identified More Than 80 Years After Discovery

Collected by the iconic American writer John Steinbeck, the octopus has received a number of scientific monikers

:focal(1024x683:1025x684)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c5/11/c511d0ea-4a92-48e5-9bd6-e663cb1625ed/40026390_10155892595418230_743929077726969856_n.jpg)

The vast majority of the more than 148 million specimens and objects in the National Museum of Natural History’s collections are off display. But everything — whether it be a moth, meteorite, moss or mammoth — tells a story that helps museum researchers make sense of the natural world. Each month, the Specimen Spotlight series will highlight a different specimen or object from the world’s largest natural history collection to shed light on why we collect.

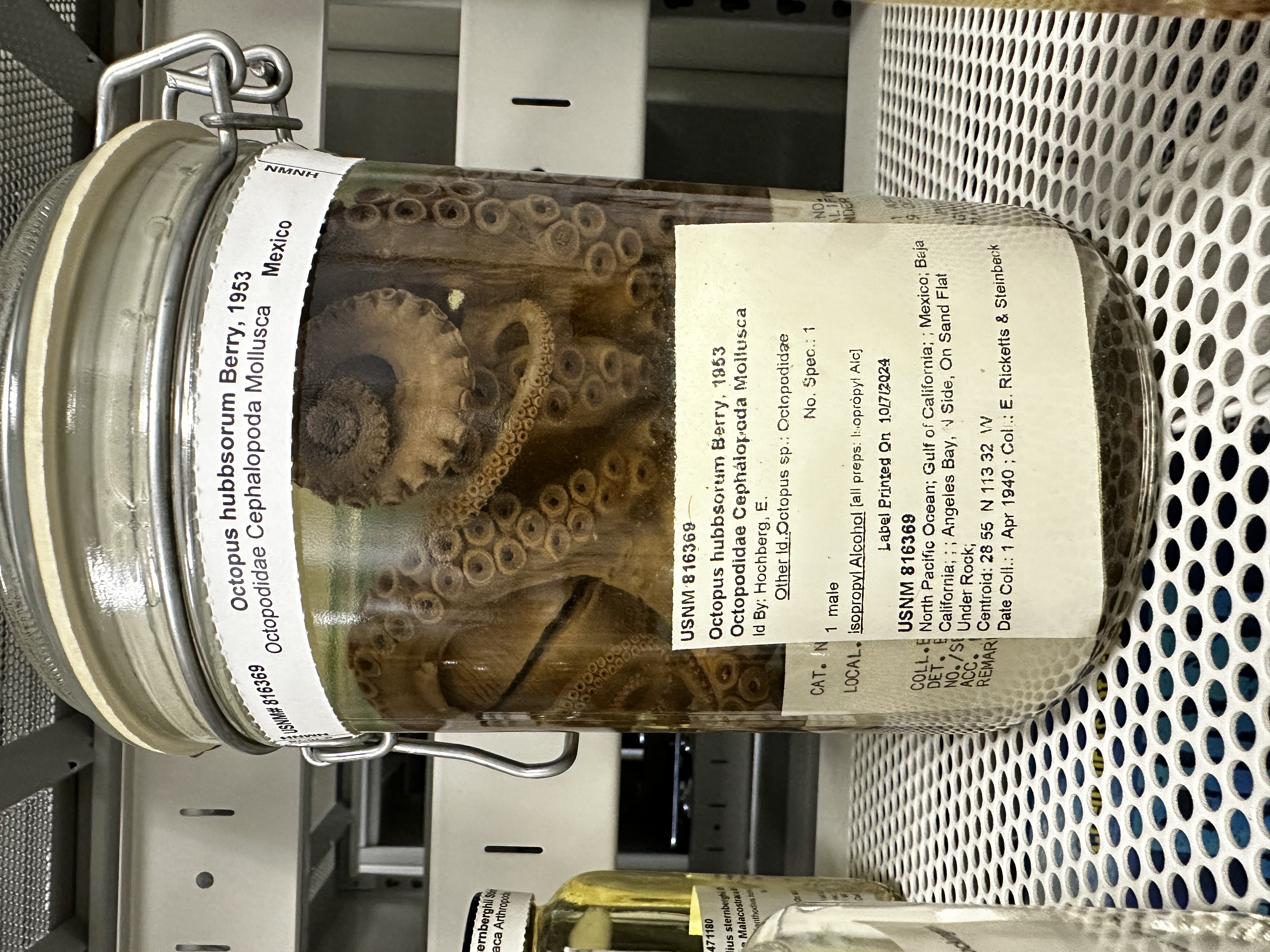

The National Museum of Natural History’s Invertebrate Zoology collection is home to some 50 million specimens that have been pickled, dried or deposited on glass slides. Each of these samples is scientifically invaluable. But one particular specimen, an octopus recently nicknamed “Berry,” has achieved celebrity status. At first glance, Berry looks like little more than a tangle of tentacles in a jar. But this octopus has quite the history.

In 1940, the octopus was collected in the Gulf of California by marine biologist Ed Ricketts and his close friend, John Steinbeck. The famed novelist, seeking escape from the public backlash over his recent book, “The Grapes of Wrath,” teamed up with Ricketts for a 6-week-long specimen collecting trip aboard the sardine seiner, Western Flyer. The pair collected hundreds of creatures living in the intertidal zone, including forty species new to science.

Steinbeck’s and Ricketts’ octopus has accrued many monikers over its decades-long residency at the Smithsonian. But it was not correctly identified until this October, when a museum researcher tracked down its true scientific name.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/16/2d/162d1b70-7c18-47c6-8be9-02ef95c8f372/npg-npg_81_14steinbeck-000001.jpg)

As Mike Vecchione, the museum’s cephalopod curator, prepared for an interview with Smithsonian Voices about Berry, he realized that the octopus was incorrectly labeled and cataloged as Octopus horridus. Spurred by this revelation, Vecchione and museum specialist Katie Ahlfeld would uncover the naming history of the specimen as it was passed among octopus experts over the last century.

Berry’s Smithsonian odyssey began on April 1, 1940. Nestled under a rock on a sandy coastal tidal flat in Bahía de los Ángelesa, Mexico, the animal was tucked away from sight and sun, perhaps resting on its commute between tide pools. Abruptly, the stone was lifted, and the octopus was collected and jarred by Steinbeck and Ricketts. Ricketts plopped the octopus in an alcohol solution along with a tan, initial ID card. There is an additional note, torn into three pieces over the decades, documenting where the octopus was caught.

The pair immortalized the eight-legged creature in their book, "Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research" published a year after their voyage. Here, the cephalopod earned its first name: Octopus sp.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e2/a8/e2a8ba20-b67b-47b7-9d33-b63a52288d96/book_spread.jpg)

Katie Ahlfeld, NMNH

"That's essentially 'Octopus, unknown species.'" Ahlfeld said. "They were able to identify it to the genus, but they weren't certain about the species name."

In October, 1953, Octopus sp. was recorded in the Smithsonian specimen catalog as identified by the legendary marine zoologist, Stillman Berry (the namesake of the specimen’s nickname). At 66 years old, Berry was considered one of the world's premier cephalopod scientists. He would go on to serve as a research associate at the Smithsonian Institution, an honorary president for the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Malacological Union, which represents scientists studying mollusks.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/da/f5da1903-70dc-43bc-859f-1816a654e3b6/sia-88-11259-000002.jpg)

Vecchione said Berry was working to identify, describe and name a new species of octopus (Octopus hubbsorum) at the time, and most likely continued the tradition of labeling the Steinbeck-Ricketts specimen as "sp." while he focused on his primary research, probably because he recognized that this specimen did not belong to any previously described species.

For over 53 years, Octopus sp. sat on the shelves of the Invertebrate Zoology department. Neither Vecchione nor Ahlfeld know exactly what happened next. However, in 2007, a new label appeared inside the specimen jar updating the animal's name to "Octopus horridus d'Orbigny, 1826." The identity of the author of the label remains one of the many mysteries in the Smithsonian collections.Seventeen years after the name change on Oct. 4, 2024, Vecchione was familiarizing himself with the octopus when he recognized the mistake on the specimen label. Firstly, Octopus horridus was an archaic name, no longer accepted since the species was reclassified from the genus Octopus to Abdopus. Secondly, Abdopus horridus was native to the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, nowhere near the Gulf of California where Steinbeck and Ricketts sailed.

This led Vecchione on an "entire day of taxonomic investigation" to figure out which octopus species this specimen represents. After digging through the literature on the Gulf of California’s octopods, he had a name.

Vecchione emailed Ahlfeld with his discovery. He was fairly certain the correct name of the specimen was "Octopus hubbsorum Berry, 1953," which cited the year the species was first described by none other than Stillman Berry. Upon examining all the labels preserved alongside the octopus, Ahlfeld and Vecchione unearthed a faded note dated July 2007 with two underlined words: "OCTOP.. ..BBSORUM." The two traced the initials left on the scribble, "FGH," to the late American cephalopod specialist, Frederick George "Eric" Hochberg.

It turned out Vecchione and Hochberg had independently reached the same conclusion nearly two decades apart.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/14/e6/14e66582-86ce-4f12-8b7e-01fbdf180a79/octopus_labels.jpg)

"Eric Hochberg looked at it because he was interested in the octopods from that part of the world," Vecchione said. "He was trying to work with Mexican colleagues and come up with a comprehensive catalog."

Hochberg eventually published a global catalog of known cephalopod species for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, which included the humble Octopus hubbsorum. A year after Hochberg’s death in 2023, his 2007 entry confirmed Vecchione's conclusion on the true identity of the "Steinbeck-Ricketts Octopus."

Eighty-four years, six months and seven days after it was collected, the “literary octopus with many famous friends,” as Ahlfeld calls it, was finally bestowed with its correct scientific name. Ahfeld also informally christened the specimen Berry in homage to its first Smithsonian handler.

Related Stories

I Spy… A Giant Squid Eye

Building a Library of Life: How Smithsonian Collections Are Revolutionizing Ocean eDNA Research

Interested in Using Museum Collections to Better Understand Freshwater Mussels? There’s Now an App for That

Museum Collections Provide Some Muscle for Mussel Conservation