NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

The Murder Mystery Linking a Bird Specimen at the National Museum of Natural History to the Mysterious Death of an Arctic Explorer

In 1871, a naturalist aboard the U.S.S. Polaris collected scientific specimens — and possibly poisoned the ship’s captain

:focal(3078x2462:3079x2463)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a4/04/a4042133-4113-4095-a101-1ba20c04a899/sia-mnh-1122a.jpg)

Skin eruptions inflamed Captain Charles Francis Hall's face, and vomit stained the delirious mariner’s sheets. It was November of 1871, and Hall was dying aboard the U.S.S. Polaris as she docked in northwest Greenland en route to the North Pole.

The sea captain was a shell of the man who'd led a scouting expedition further north not two weeks earlier. The Arctic explorer had peculiarly fallen ill the day he returned from the harsh tundra after drinking a single cup of coffee. Rummaging in his kit, medical officer and chief scientist Emil Bessels retrieved a syringe allegedly filled with quinine, an antimalarial drug, and administered the latest treatment. By November 8, Hall was dead./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ab/d3/abd317f2-ccd9-4ebd-9433-6d5893d9a422/damsmdm_nmah-ac0702-0000018-001.jpg)

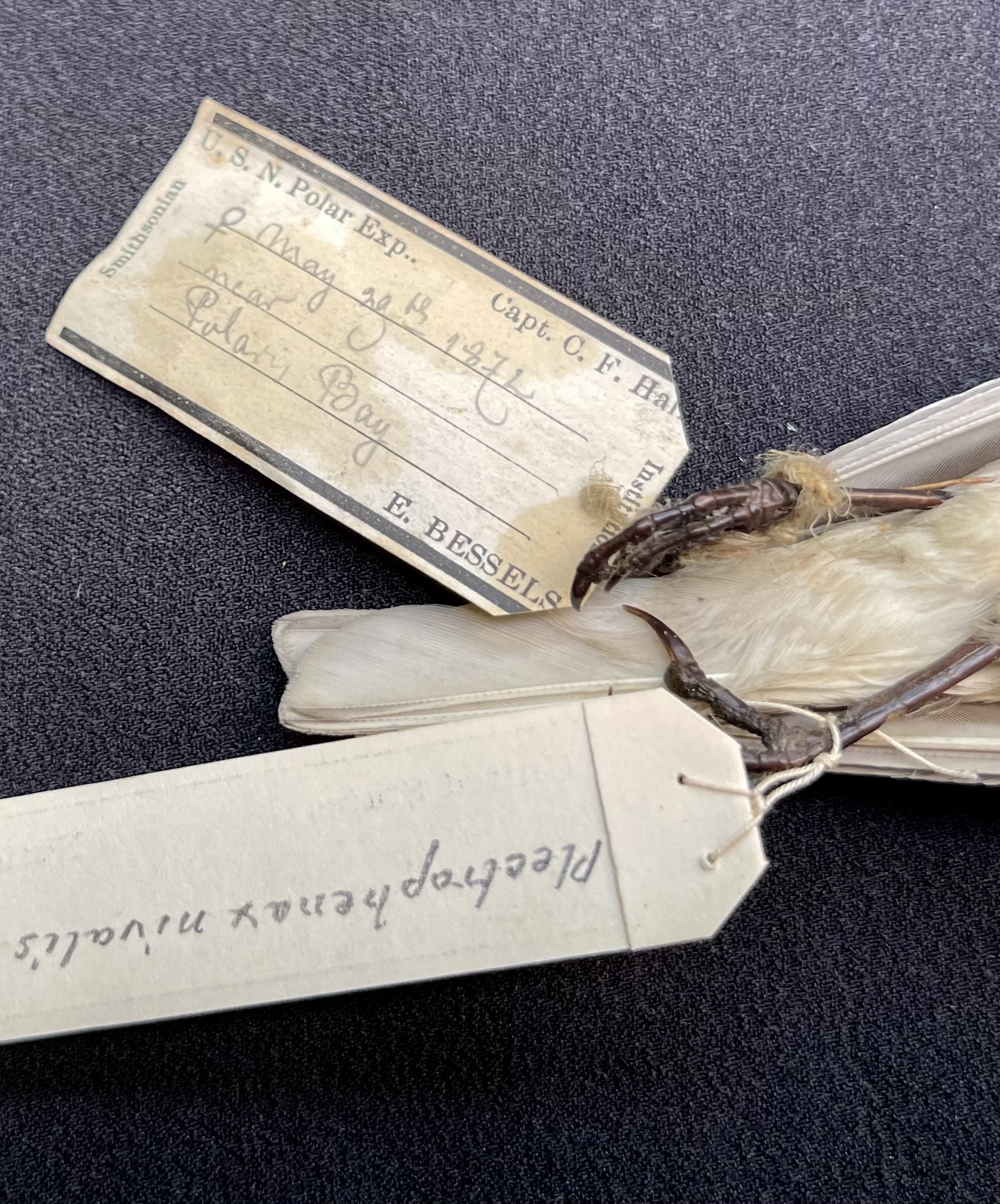

Six months later, Bessels collected a female snow bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis) in the Greenland coastal basin where Hall was buried. To preserve the bird, Bessels likely used arsenic — the same poison that scientists now know killed Hall.

Many items in the National Museum of Natural History's collections hail from historic expeditions. Robin Duska, a veteran volunteer in the Bird Division, was cataloging the snow buntings in the collection when she encountered Bessels’ bird. The label attached to the palm-sized bird's right foot said the specimen was caught on May 29, 1872, near Greenland’s “Polaris Bay” by “E. Bessels” on the U.S.N. Polar Expedition.

Hall, believing his crew was the first to venture this far north on Greenland’s western coast, bestowed his ship’s name on the land where they docked. In reality, “Polaris Bay,” now Hall Basin, had long been known to Indigenous communities including the Inughuit/Avanersuarmiut.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/39/f0/39f0d7b4-0110-452c-862f-b1584e9988b4/duska_in_bird_division.jpg)

Duska was familiar with polar voyages. The 19th century featured an international race to the North Pole, a competition that drove the United States Navy to commission several expeditions. The naturalists aboard those ships often donated invaluable specimens to the fledgling Smithsonian Institution. However, she had never heard of the Polaris expedition.

The voyage was ill-fated even before its captain’s death. Hall struggled to control a rowdy crew and frequently clashed with several of his sailors, including Bessels, a young surgeon and naturalist from Germany. After Hall died, part of the crew became stranded on an ice floe and the rest ran aground in Greenland. Miraculously, Hall was the doomed mission’s only fatality.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8b/d8/8bd82196-ac1f-4ce4-9ea1-7e3e5eea6b5f/4a13983u.jpg)

As she read up on the expedition, Duska was surprised to realize that the snow bunting’s collector, Bessels, was the primary suspect in Hall's mysterious death. In his final weeks, the captain had displayed textbook symptoms of arsenic poisoning.

"Naturalists at the time routinely used arsenic," Duska said. "That's why the specimens we have from the 1800s are in such great shape."

Humans have utilized arsenic as a poison, pesticide, antifungal treatment and medicine since 500 B.C. The substance's bug-deterring nature made it one of the principal components of taxidermy from the 18th to late 20th century.

Naturalists had realized that gutting animals of all soft tissue —things that would degrade, smell and decay — was insufficient for preserving the skin. The specimens were still prone to consumers of necrotic flesh, including ravenous dermestid beetles.

"If you found a dead animal on the side of the road and kicked it over, you'd see all kinds of little bugs and creepy crawlies coming out," said Christopher Milensky, the collection manager of the museum’s Bird Division. “Those same beetles can eat through museum specimens.”

Specimen skins were thus turned inside out and brushed with a marinade of soap, water and arsenic. The skins were then reoriented, stuffed with cotton and sewn closed. Some naturalists dusted arsenic powder over the end product for additional protection.

Unfortunately, the commonality of the practice meant scientists seldom mentioned preservation methods on their specimen data. Even in the rare event that Bessels used an alternative chemical on the snow bunting, an arsenic test to the feathers could read positive due to contamination from its shelf-mates of the same era.

What is known for certain is that Bessels, as the chief surgeon and naturalist of the U.S.S. Polaris, had access to multiple forms of arsenic. Furthermore, the ship's navigator, Captain George E. Tyson, later testified that four days before his death, Hall accused Bessels of "wanting to poison him."

Bessels may have had a personal reason to poison his captain. In 2016, archival material was discovered that linked both men to pioneering artist Vinnie Ream. Ream was the first woman ever commissioned to create art for the United States Government and sculpted president Abraham Lincoln’s memorial statue in the Capitol Rotunda. Both Bessels and Hall wrote affectionate letters to Ream during their expedition to the Arctic.

For the record, Bessels maintained his innocence. In a story published in the Alexandria Gazette newspaper in 1873, Bessels claimed that Hall had died of apoplexy (which could be caused by a cerebral hemorrhage). The story quoted Bessels saying, “It was only during the delirium of illness that he manifested great fears of being shot or poisoned.”/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/e7/03e7d783-1cd0-4f83-8724-41f33baa1f38/hall_orig.jpg)

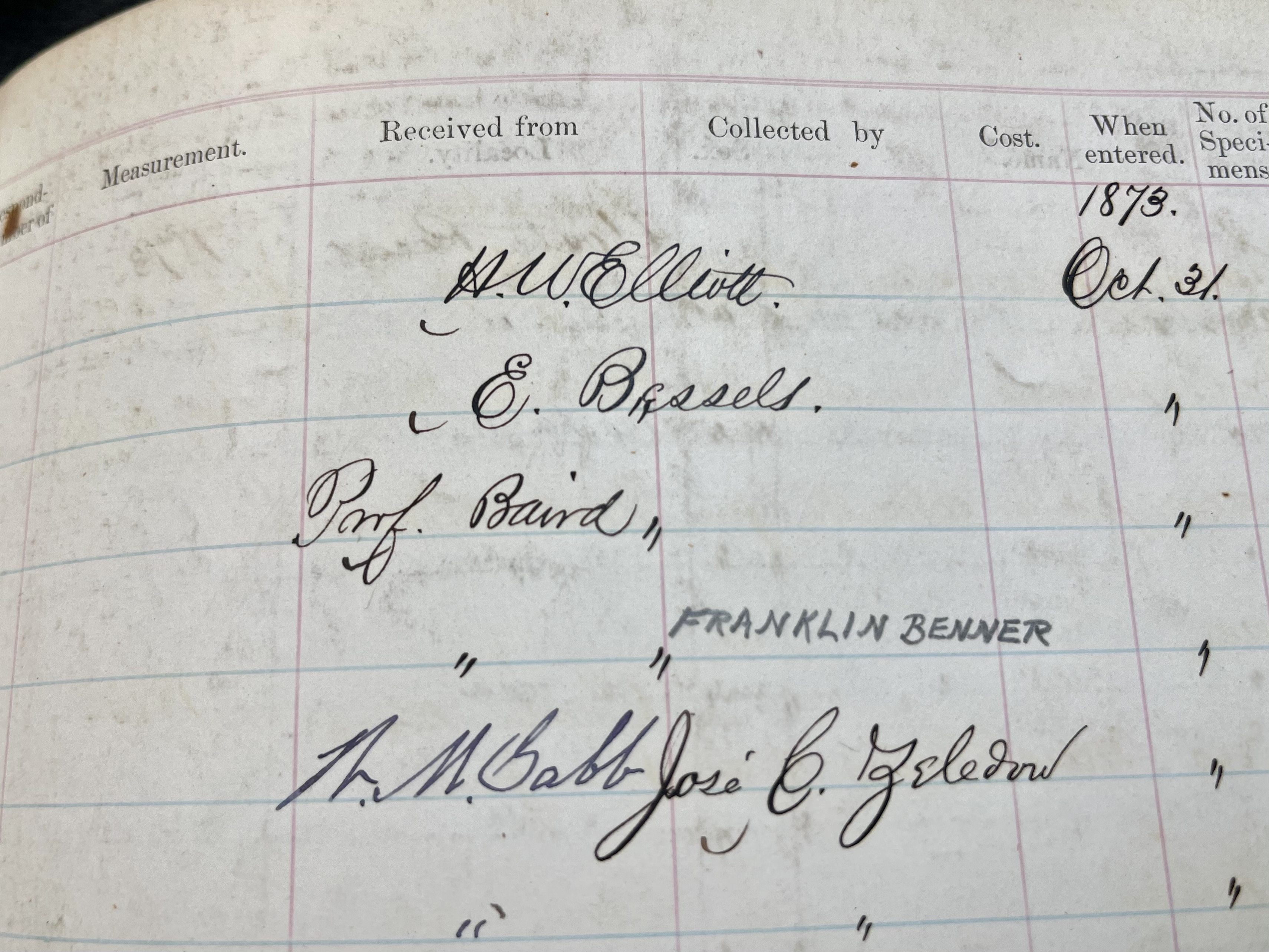

Because the Polaris expedition was funded by the Navy, many of the specimens and archival material from the journey ended up at the Smithsonian. Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian, had overseen the scientific research of the Polaris expedition and was in direct contact with Hall and Bessels (Hall even named the northernmost point he witnessed “Cape Joseph Henry”). When Bessels returned to Washington, Henry gave the naturalist space in the Smithsonian Castle to further examine and summarize his findings from the voyage.

While Bessels was never charged in connection to Hall’s death, many remained skeptical of his innocence. They may have been correct — a 1968 analysis of Hall’s exhumed hair, fingernails and skullcap confirmed the captain had ingested significant amounts of arsenic in the final two weeks of his life.

To Duska, it was like a puzzle piece fell perfectly into place. "The fact that arsenic was used by a person who could have been inclined to murder is something,” Duska said. “He could have just added a little bit of arsenic here and there to the tea at night.”

However, without concrete evidence linking Bessels and the fatal dose of arsenic, the truth behind this Arctic cold case remains as silent as the snow bunting that flew over Hall’s grave.

To learn more, listen to the episode on Bessels and Hall on the Smithsonian’s Sidedoor podcast.

Related Stories

How A 190-Year-Old Shorebird Preserves Darwin’s Legacy

How Arctic Anthropologists are Expanding Narratives about the North

How Lugging a Liquid Nitrogen Tank into the Amazon Helped Spark Ornithology’s Genetic Revolution

Across the Smithsonian, Researchers are Working Together to Save Virginia’s Birds