NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Scientists at the National Museum of Natural History Discover Two Squirrel Species Long Obscured by Mistaken Identities

Using a variety of techniques, the researchers realized that two subspecies of squirrels from Southeast Asia were actually unique species in their own right

:focal(1024x736:1025x737)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/39/cd39918d-1c30-4cee-83c6-1e30d673f1c4/original-1.jpg)

ayuwat via iNaturalist

In many urban environments, squirrels reign supreme. These bushy-tailed rodents are nearly ubiquitous and are often unfazed by their human neighbors. As they scurry about, squirrels infiltrate attics, gnaw through power lines and pilfer seeds from bird feeders with the proficiency of a safe cracker. But squirrels are far from pests. These wide-eyed critters bring a number of beneficial qualities to the table. For example, as they cache acorns, squirrels help trees disperse seeds throughout their environment.

Yet despite their abundance, many squirrel species remain understudied according to Arlo Hinckley, a research zoologist and postdoctoral fellow in the National Museum of Natural History’s division of mammals. Some, like flying squirrels, live high up in the canopy and are tough to observe and sample. Other squirrels struggle to catch a researcher’s eye due to their drab coloration. “We're a very visual species and oftentimes the brownish squirrels get overlooked,” Hinckley said./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4c/c9/4cc932b5-06f2-42c1-a694-9e9ef055c49a/arlo_hinckley_-__dsc2260_copia.jpg)

As a result, squirrels as a whole have been a tricky subject for taxonomists. The squirrel family contains nearly 300 known species ranging from ground-bound prairie dogs to purple squirrels as big as cats. But Hinckley believes there are many more squirrel species to be described, including several that have been previously misidentified by researchers.

Hinckley and colleagues recently re-evaluated two such squirrel species in a paper published last month in the journal Vertebrate Zoology. These two species — the Southeast Asian striped squirrel (Tamiops barbei) and the southern gray-bellied squirrel (Callosciurus concolor) — were previously thought to be subspecies of other squirrels. However, the new paper found that the squirrels were distinct enough to warrant recognition as unique species and elevated them to their proper places in the squirrel family tree.

Hinckley began studying these squirrels during his thesis, and continues to do so with his advisor Melissa Hawkins, the museum’s curator of mammals, and Jesus Maldonado, a research geneticist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. The three were using the rodents to determine how species differed across the Isthmus of Kra, a narrow stretch of land on the Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia. Sandwiched between two seas and carved by mountain ranges, the Isthmus of Kra marks a biological transition for wildlife. Here, the species found northward in Indochina are largely replaced by animals found in Sundaland (which contains the Malay Peninsula and several Indonesian islands) to the south.

Two of the squirrel species that inhabit this dynamic region are the gray-bellied squirrel (Callosciurus caniceps), a forest-dweller with a feathery tail, and the Himalayan striped squirrel (Tamiops mcclellandii) a pint-sized rodent resembling a chipmunk. Hinckley, Hawkins and Maldonado examined specimens of both species collected across the Isthmus of Kra. But as they examined samples representing each species, they noticed striking variations among the individual squirrels. This suggested that the researchers were looking at multiple distinct species.

It can be difficult for zoologists to accurately split species. While taxonomy offers a systematic and ordered system for classifying animals, determining where to draw the line between related populations and different species can be sticky. According to Hinckley, species are constantly evolving and changing, making speciation more of a continuum than an abrupt boundary. “It can sometimes be difficult to know where to set the species threshold,” he said.

To revise the taxonomy of the gray-bellied and Himalayan striped squirrels, Hinckley, Maldonado and Hawkins teamed up with an international team of researchers including Noriko Tamura, from Japan’s Tama Forest Science Garden, and Jennifer Leonard, from Spain’s Estación Biológica de Doñana-CSIC.

In addition to the genetic samples they analyzed in the lab, the team explored several other lines of evidence. For example, they tracked the squirrels’ distribution through iNaturalist, an online database where citizen scientists upload photos and videos of plants and animals in their area. The researchers also listened to audio recordings of gray-bellied squirrel calls and determined that southern gray-bellied squirrels have a noticeably different call from their northern neighbors.

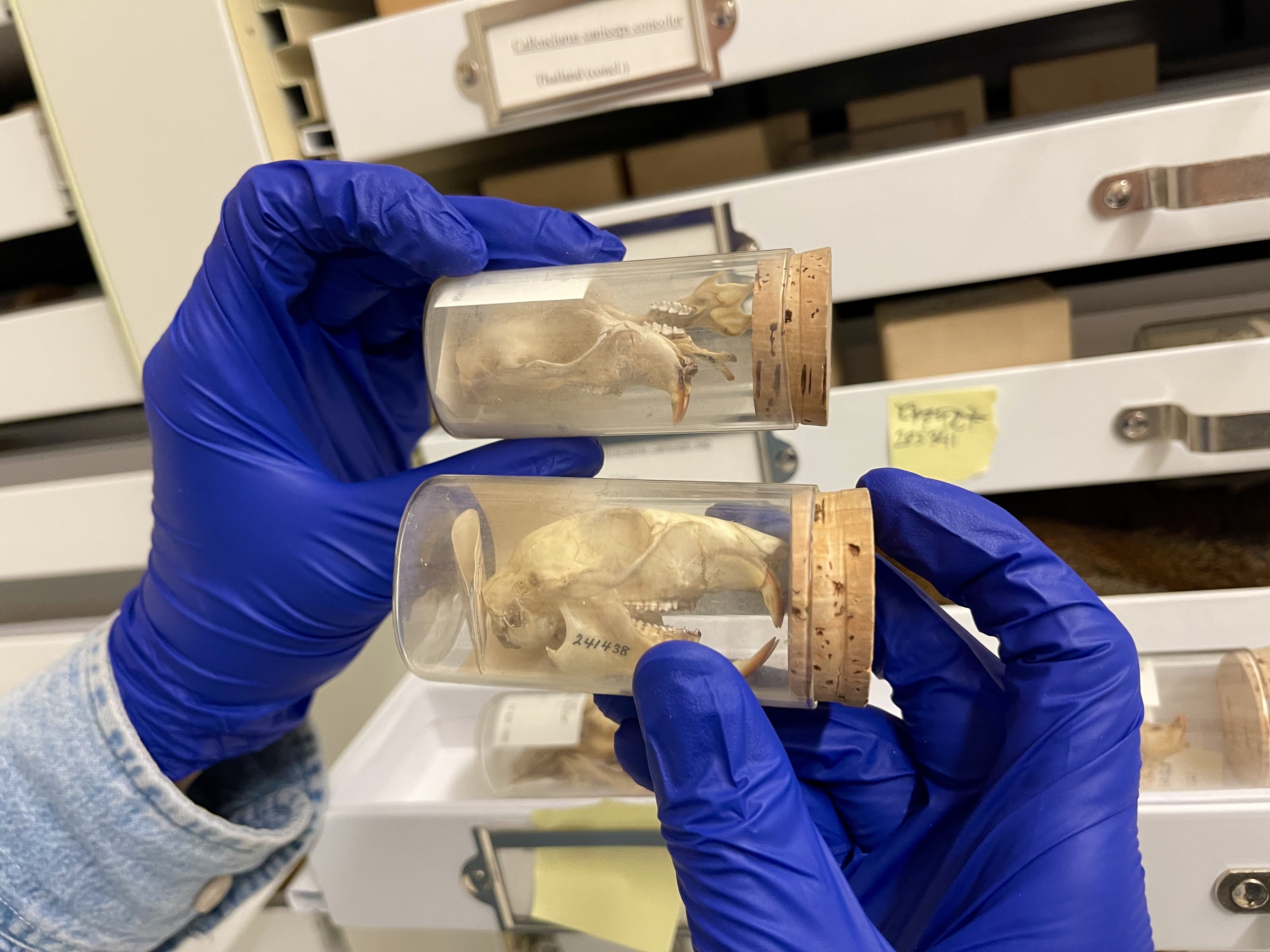

The scientists also made careful observations of the squirrels’ pelts, skull and tail shapes. The coloration of the squirrels’ fur was particularly helpful for differentiating between the two groups of striped squirrels. The Southeast Asian striped squirrel (T. barbei) has a brighter belly and a paler tail than Himalayan striped squirrels (T. mcclellandii).

The differences between the gray-bellied squirrels were tougher to see, so the team peered deeper. They used a CT scanner to pinpoint a telltale feature of a squirrel’s skeletal anatomy — the baculum. This shaft-like bone is found in the penises of squirrels and other mammals and often differs subtly in shape between species. The team found that the southern gray-bellied squirrel (C. concolor) sports a complex baculum featuring a hook-like tip slightly different from the baculum possessed by its closest relative, the northern gray-bellied squirrel (C. caniceps).

After examining these various lines of evidence, the team could confidently determine that C. concolor and T. barbei were each distinct species, essentially doubling the number of squirrel species the team examined.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/57/b657e15d-b66f-4c71-81c7-e6bf5ca4fa54/original.jpg)

According to Hinckley, knowing who is who among the region’s squirrels will aid conservation efforts. “Distinguishing species ensures that each squirrel receives the protection it needs, rather than being overlooked due to misclassification,” he said. Some of these squirrels are also consumed by local humans or sold as pets. Knowing which squirrels people eat or keep at home could potentially help scientists trace the spread of zoonotic diseases between wildlife and humans and prevent outbreaks.

Hinckley thinks there are many other hidden species of squirrels suffering from a similar case of mistaken identity as the two species described in the new study. He and his colleagues are currently working through the museum’s squirrel collection in search of other overlooked species. Like a squirrel stockpiling acorns, museum scientists have been depositing tens of thousands of squirrels here, providing a global snapshot of these varied and misunderstood rodents.

Related Stories

Smithsonian Scientists Discover New Species of Hedgehogs Hiding in Plain Sight

Shrew Are You? Scientist Discovers Two New Species of Shrews in Museum’s Collection

Meet the Scientist Extracting Ancient DNA From Squirrels and Lemurs

Mummified Shrew Discovery Unearths Ancient Egypt’s Wetter Climate