Remembering President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/npg5-1_lincoln_emancipation.jpg)

Fearful of alienating the Union’s precariously loyal slaveholding states, President Abraham Lincoln had, at the outset of the Civil War, cautiously disavowed any intentions of putting an end to slavery. The North, he insisted, was fighting not for the liberation of black bondage but for the preservation of the Union. In the spring of 1862, however, as Northern resolve waned in the wake of battlefield failures, Lincoln quietly weighed the tactical advantages of striking a blow at slavery in the seceded states. By early summer, with painstaking deliberation, he was drawing up the Emancipation Proclamation, granting freedom to all slaves in Confederate-held territory.

Made public in September and officially signed on January 1, 1863, the proclamation marked the philosophical turning point in the Union’s war efforts. Because it applied only to slaves residing behind enemy lines, the South was partly correct when it declared the president’s decree little more than a hollow gesture. Nevertheless, in a larger sense, Lincoln’s measure underscored his heartfelt faith in and vision for the future of the reunited country. For the time being, the proclamation clothed the Northern cause in a new moral imperative and made the eradication of slavery at war’s end a certainty.

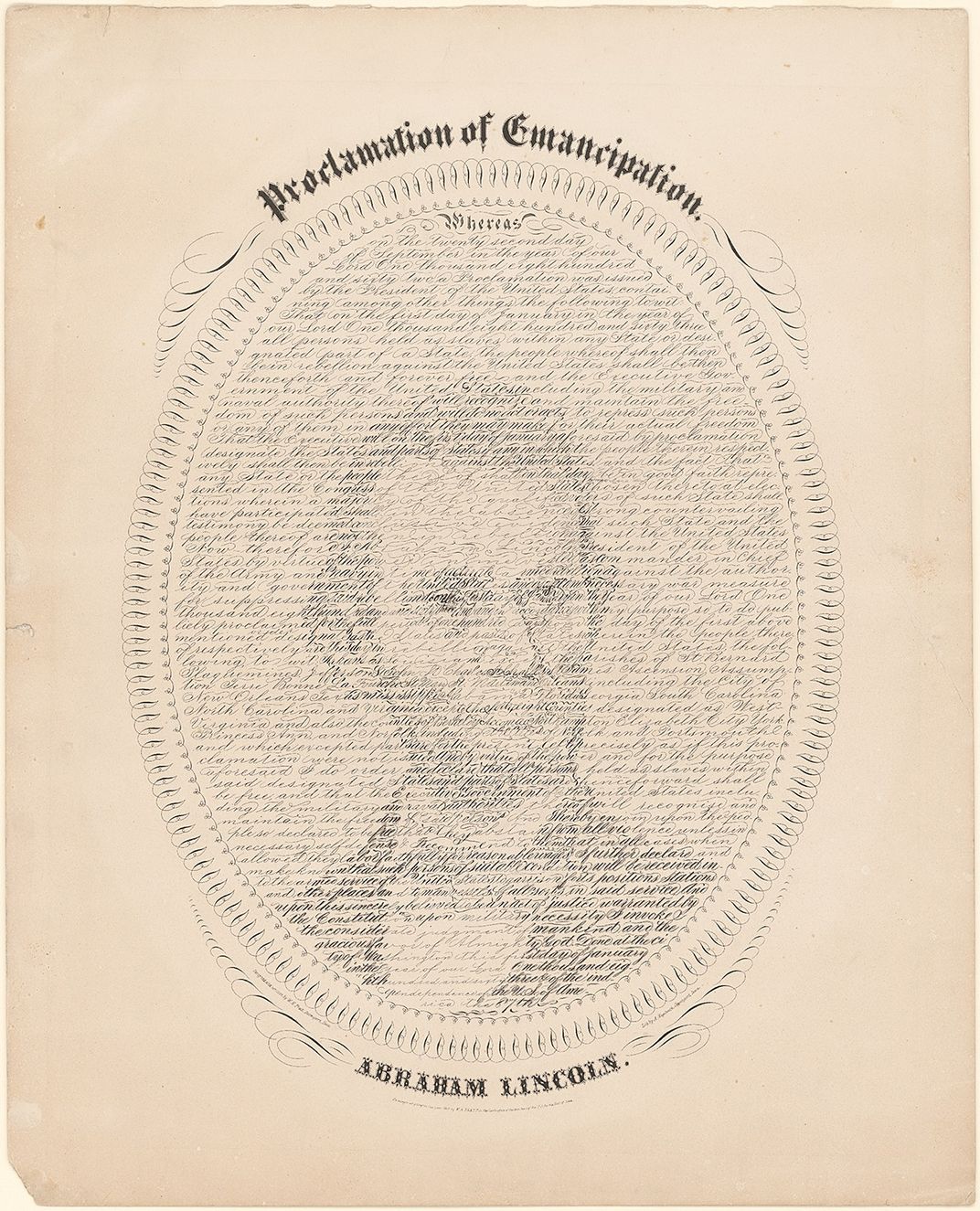

Yankee printmakers captialized on the positive receiption of the Emancipation Proclamation by issuing scores of commemorative prints. In this lithograph, Abraham Lincoln's portrait is formed from the text of the proclamation.

For portraitist Francis B. Carpenter, Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation represented the consummation of the nation’s founding ideals. It was therefore with a special sense of patriotic mission that he arrived at the White House in 1864 to execute his monumental painting commemorating the first cabinet reading of the historic decree. In devising the composition for his nine-by-fifteen-foot canvas, Carpenter took great care to make the background details of the event as accurate as possible. As for the actual moment depicted, Carpenter derived his inspiration from the president’s own narrative of the proceedings. In the final rendering, Lincoln listens attentively as Secretary of State William Seward—his hand poised as if to stress his point—urges him to delay the announcement of the proclamation until after a battlefield victory. Soon after Carpenter completed the painting, it was exhibited in several major cities, and at Lincoln’s second inaugural in 1865, the work was placed on view in the Capitol, where it has hung permanently since 1878. Prints of Carpenter’s work proved immensely popular. For years, they decorated schoolrooms and other public places across the country.