NATIONAL ZOO AND CONSERVATION BIOLOGY INSTITUTE

Eyes and Ears on the Amazon Rainforest

Camera traps and acoustic recorders allow researchers to covertly monitor wildlife

:focal(700x525:701x526)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/img_0186.jpg)

Wild animals are very elusive. In order to learn important things about their behavior and life history, scientists have come up with equally sneaky ways to spy on them. Camera trapping and acoustic recording are two ways we can covertly monitor wildlife. They allow us keep our eyes and ears on wildlife, even after we leave the forests we study.

Camera traps are motion-sensitive cameras that snap a picture whenever they detect movement. Their passive infrared motion sensors “see” animals by sensing the difference between the ambient temperature and the sudden arrival of a warmer body.

We install the cameras on tree trunks and leave them in the rainforest for about six months. We also hang acoustic recorders about 5 to 6 feet above the ground near each camera trap. The audio recordings are collected over two week periods every few months.

On the ground, camera traps are a great tool for capturing information about large- and medium-sized mammals, as well as large birds that live on the forest floor. Meanwhile, canopy camera traps can give us a lot of information about animals that live in trees, called arboreal animals. Though we mostly see mammals here, the cameras sometimes capture a perching bird or reptile.

But these animal groups make up just a small portion of the life in a tropical forest. Acoustic recorders can provide invaluable information about the presence and behavior of animals that produce sound — many of which would never be photographed by a camera trap — such as frogs, birds, insects and even some mammals (like bats and monkeys).

At the Center for Conservation and Sustainability, we use both of these methods to monitor wildlife in a rainforest in Peru. We are studying this area of rainforest before the construction of a pipeline, so we can understand its potential future impacts on wildlife. The project began last year, and the first cameras and recorders were installed in July.

With the information we collect, we can propose different ways to minimize the pipeline’s impacts, and we can learn how effective those management strategies are. Continue below to see and hear some of the interesting things we have found so far.

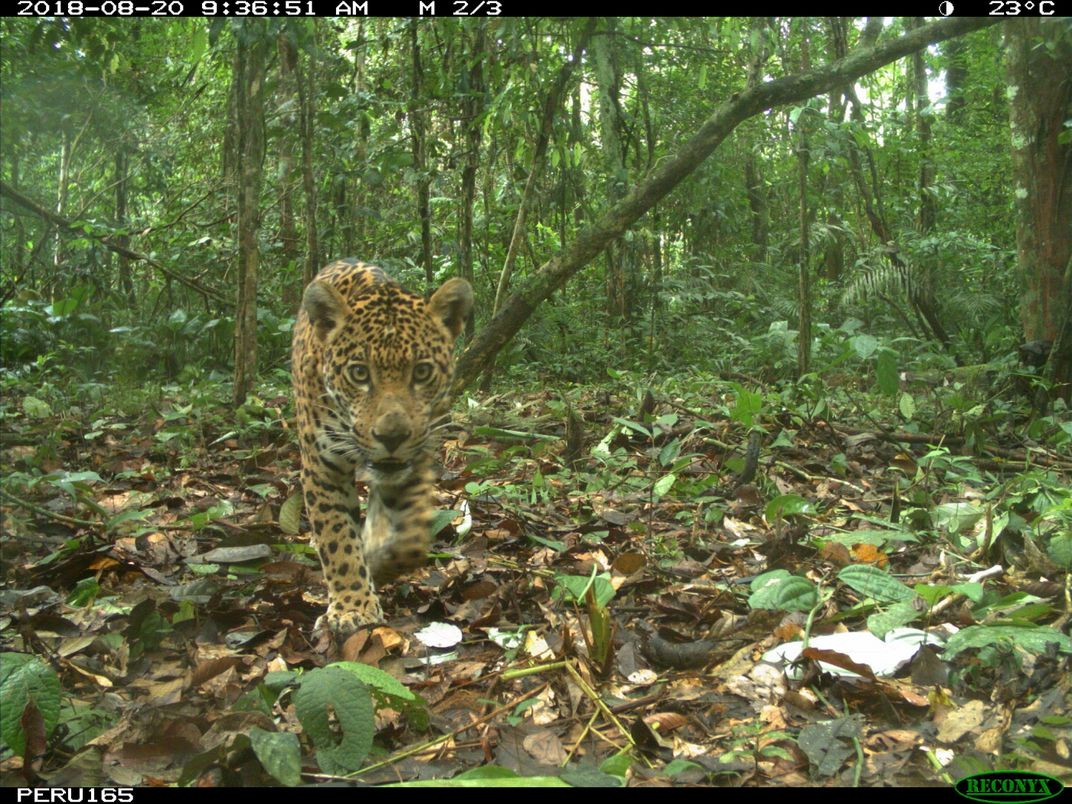

Camera traps are great for spotting big cats like jaguars (Panthera onca). Like the other big cats in the Panthera genus, jaguars can roar. However, they rarely do so, which makes them difficult to detect with recorders.

Jaguars range from North America to northern Argentina (though it’s unclear if any remain in the U.S.). They use very large territories, so their conservation requires protection across large tracts of land.

Pumas (Puma concolor) — also known as cougars, panthers or mountain lions — are big cats that can be very vocal. Acoustic recorders may capture sounds like cries and meows that help us understand how these animals communicate, but camera traps allow us to see their behavior.

In this camera trap photo, a puma drags what appears to be a howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) through the forest. Pumas are known to hunt these monkeys, but records of this behavior are rare.

Howler monkeys (Alouatta seniculus) seldom come down to the forest floor, so we were lucky to capture them in one of our ground camera traps. They are known as the arboreal (or tree-dwelling) “cows” of the rainforest, because they eat a lot of leaves. Many mammals have difficulty digesting leaves, but like cows, howler monkeys have special adaptations in their guts that allow them to do so.

In the case of howler monkeys, acoustic recorders can also tell us a lot about their presence and activity. Every morning, howlers let other groups know where their territory is by “howling” loudly enough to be heard for a few kilometers!

Thanks to these vocalizations, it’s easier for us to identify howler monkeys and register their presence using acoustic recorders.

See if you can hear the howler monkeys in this recording:

Other primate species, like titi monkeys (Plecturocebus discolor), are even more unlikely to come down from the trees. Luckily, they also call out to other groups to mark their territories. These songs are called duets, as two individuals usually alternate high and low vocalizations.

Listen to one of the titi monkey duets our team recorded:

Although camera traps are our best bet to monitor ground mammal activity (and sometimes arboreal mammal activity too), birds are mainly active in the canopy. Some of them move too fast or are too small to be captured in a photo. This is another area where acoustic recorders shine.

White-throated toucans (Ramphastos tucanus) fly and jump all the way to the highest clear branch they can find to sing — often just before or after a good rain. Their loud “Juan! Juan! Tío Juan!” call can be heard for at least a few hundred meters. But who is Juan? We’ll probably never know!

Listen to white-throated toucans calling for him in one of our recordings:

Practically invisible during the day, a bird known as the common pauraque (Nyctidromus albicollis) blends almost perfectly with the leaf litter on the ground of the rainforest. Just like other members of the Caprimulgiformes order, it relies on camouflage to stay safe during the day and goes hunting for insects when night falls.

Another popular Amazonian bird in this order is the common potoo (Nyctibius griseus), known locally as “ayaymama.” Its call, which some say sounds like children calling for their mother, inspired a well-known myth.

How would you feel if you heard this sound at night while standing alone in the rainforest?

A sweet, soft whistling can be heard during the night and day in the rainforest, and it usually means there’s a tinamou bird nearby. There are different species of tinamous in the Amazon rainforest. Thanks to acoustic recorders, we’ve identified at least six of them in Morona, the region of Peru where our study site is found.

Each tinamou species has its own unique calls and whistling patterns, making them easy to identify by sound. The great tinamou whistles continuously. Some people say they sound like sad whales.

What do you think?

Great tinamous also lay colorful eggs, which contrast with the drab leaf litter. The little tinamou (Crypturellus soui) is less conspicuous, laying eggs with brown shells. Its whistle also differs from its slightly larger cousin.

Can you hear the difference?

Common in our audio recordings, thanks to their raucous squawks, are chestnut-fronted macaws (Ara severus). Unlike their cousins, these macaws don’t sport brightly colored feathers all over their bodies. They are better camouflaged, blending in with the green canopy … that is until they unfurl their beautiful blue and reddish wings.

Chestnut-fronted macaws rarely appear in canopy camera trap pictures, but these highly social birds make plenty of noise for our recorders. Their calls can be captured over long distances, allowing us to document their presence and movement within an area over time.

Listen to the volume of their squawks increase as they fly toward the recording site:

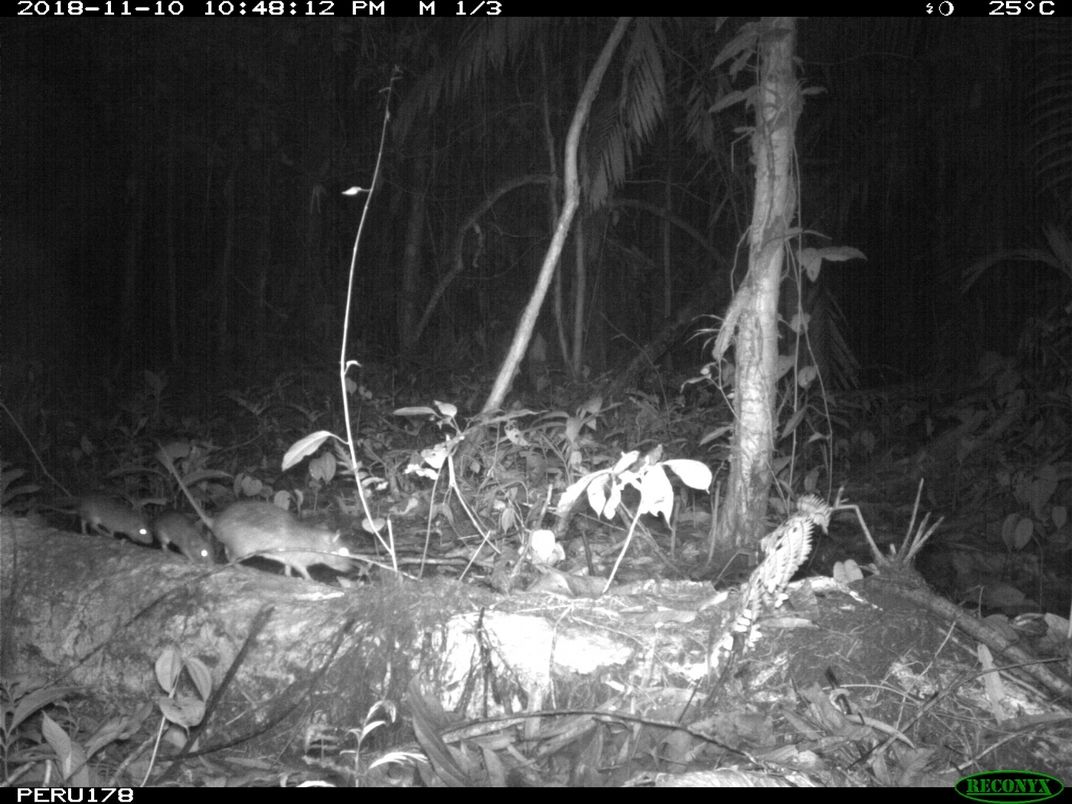

Acoustics can tell us a lot and help us to document species that we would never see in camera trap photos. But there are some things we can’t learn from acoustic recorders. By only listening to sounds, we can’t know if an animal is pregnant, carrying a juvenile or being followed by its litter — like this spiny rat mother (family Echimyidae).

Camera traps and acoustic recorders are wonderful tools on their own, and even stronger when used together. They allow us to see and hear wildlife behaving as if we weren’t there — precisely because we’re not.

Learn more about this project and listen to other acoustic recordings from the field