NATIONAL ZOO AND CONSERVATION BIOLOGY INSTITUTE

Inside the Zoo: A Rare and Life-Preserving Cheetah Surgery

With the help of 3D modeling technology, a team of veterinary experts successfully carried out a rare spinal surgery on an 11-month-old cheetah cub at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute in August.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e7/79/e7794fa2-1d1f-49fe-8fe2-8c51c46a225e/20240827-l1122110-41rp.jpg)

It wasn’t immediately obvious to Smithsonian animal care experts that Freya had a serious condition. For the first few months of her life, the young cheetah blazed around the grassy fields, leaping and dash-tackling her siblings just like a normal cub.

In fact, Freya had recently been featured along with her four siblings on the Zoo’s Cheetah Cub Cam, which spotlighted the cheetah family after their birth on September 12, 2023, at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Va.

But when a keeper team conducted a routine health inspection on all five cubs in March 2024, they felt a soft bump on Freya’s shoulder. The veterinary team followed up with additional radiographs, and found a malformation in Freya’s spine that was causing the vertebrae to twist into a c-shape.

Spinal malformations can quickly become serious for animals. For vertebrates—think mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and humans—the spinal cord controls an organism’s ability to move freely. This delicate bundle of nerve fibers is surrounded by a protective casing of vertebrae (backbones), tendons and muscles. Together, this entire structure makes up the spinal column.

Freya’s condition was causing a twisted "hump" to form in her back. This left her at risk for serious injury to her spinal cord. CT and MRI scans taken in April confirmed the cub had already sustained minor spine damage as the bend in her spinal cord bumped up against the inside of her vertebrae.

“If we didn’t correct it, she would slowly lose mobility over time. And that’s not something we would want to put her through,” said Dr. Adrienne Crosier, staff biologist and lead care supervisor for the cheetahs at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

Without the ability to walk, feed herself or safely interact with her siblings, the cub’s quality of life would be severely degraded. Veterinarians would most likely consider euthanasia to be the most ethical course of action.

“For us, it’s all about quality of life. We want to do the best for our animals, but we don’t want her quality of life to be so diminished that on the other side of this, we asked ourselves if it was the right choice,” said Dr. Crosier.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/a8/67a83543-d196-4d35-9246-bc409fc4980e/20240917-817a4883-03rp.jpg)

Staff at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute stepped in immediately to care for the cub. An initial assessment led by Smithsonian veterinarian Dr. Kristina Delaski revealed the cub was not in immediate danger. Freya’s back muscles were doing a good job of stabilizing her spinal column, but her long-term health was at risk.

Dr. Delaski organized a diverse group of veterinary experts to review options for a treatment plan. The group employed the services of a sports medicine veterinary practice, whose technicians created a 3D model of Freya’s spine from images obtained via CT scan. With this model, the team could get a close look at the malformation without having to subject the cub to invasive follow-up exams.

Meanwhile, animal care teams led by Dr. Crosier carefully monitored Freya for signs of further injury, and veterinary technicians began a daily regimen of laser therapy to reduce swelling and improve her chances of recovery.

While it’s not clear how the injury formed, veterinarians theorize her spinal vertebrae may have been fractured during or shortly after birth, and then healed out of alignment.

After a gauntlet of consultations and medical reviews, Dr. Delaski united Freya’s network of caregivers around a plan. The cub would undergo surgery to stabilize her spine.

Inside the operating room

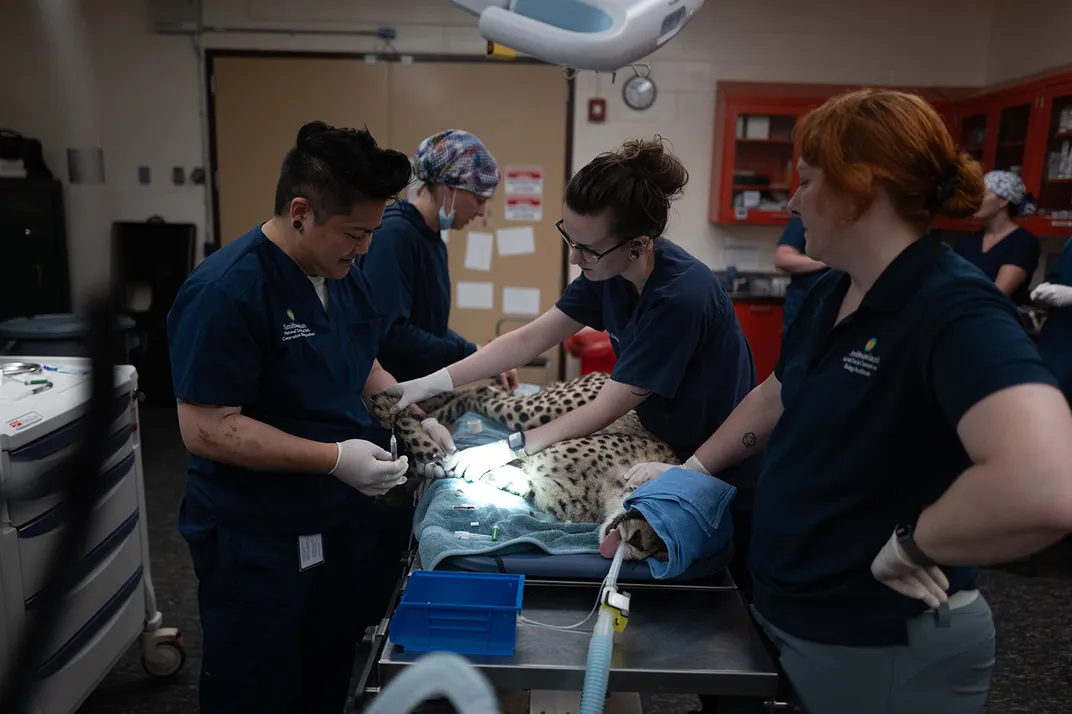

On August 27, 2024, about a dozen experts in blue medical gowns and Smithsonian scrubs gathered around 11-month-old Freya as she rested on the veterinary hospital operating table. The procedure was led by Dr. Martin Young of Bush Veterinary Neurology Service, a surgeon with experience operating on large carnivores.

The surgery was complete in a little over 2 hours. Freya’s care teams were relieved to find the cub stable and awake—if not a little groggy—a few hours after the surgery. She was able to walk around in her recovery area later that day.

The surgery should enable Freya to “maintain a comfortable and functional lifestyle for a longer period of time with significantly less suffering,” said Dr. Young.

Animal care staff reunited Freya with her family eight days later.

A promising future

Staff are confident the surgery will add years of good health to the young cub’s life. As of October 2024, Freya has regained her strength, is no longer on medications, and appears to be healthy and fit.

Freya's condition means she will never directly participate in the Smithsonian’s cheetah breeding program, said Dr. Delaski. But she might be a good candidate for continuing her genetic lineage via an embryo transfer later in her life.

For now, Freya will continue to enjoy life as a healthy young cheetah. Animal care teams expect to send her sister, Ojore, and three brothers, Kasi, Jasiri, and Motsi, to participate in breeding efforts at other zoos when they get older. However, Freya and her mother, Echo, will likely be lifelong companions going forward.