History Hiding in Plain Sight

Shining a spotlight on an integral, but largely unexamined, community in Oklahoma

:focal(375x250:376x251)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/VIGIL.jpg)

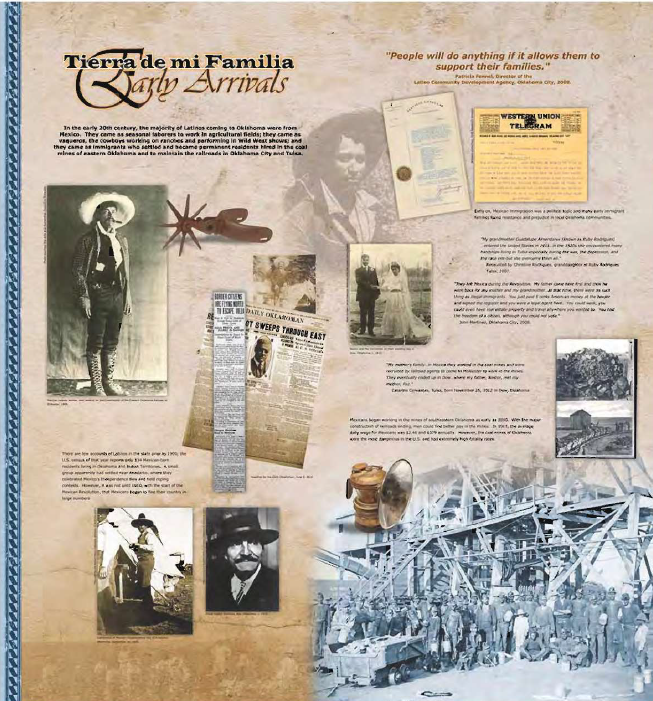

The Oklahoma History Center (OHC), in Oklahoma City, part of the 127-year-old Oklahoma Historical Society, received a grant last year from the McCarthey Dressman Education Foundation generously funding the creation, by the OHC Education Team, of a "Latinos in Oklahoma History" educational trunk. Although Latinos comprise 10 percent of Oklahoma’s population and are the largest minority group in the state, the coverage of Latino history, impact, experience, or culture in Oklahoma by historians or museum professionals was largely incomplete. In 2008, the Oklahoma History Center created its first chronicle of Latino experience in Oklahoma with a 1500 square foot temporary exhibit called Tierra de mi Familia. The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture offered two articles, one on “Hispanics” and the other on “Mexicans.” These efforts, along with a handful of articles and a slim volume entitled The Mexicans in Oklahoma by Dr. Michael M. Smith and a small book by Yolanda Charney called Latinos Presentes, combined to form the full extent of easily accessible histories focused on the Latino experience in Oklahoma.

The OHC EDU Team, coordinated by project lead educator Carrie Fox, hoped that, while general, public-facing histories might not be available they would find additional information in academic journals, dissertations, and within archival collections. While they were able to develop a more complete source list, the scope of study sources remained limited. They then understood how much of this part of our state’s history was waiting to be explored.

Their first step was to reach out to individuals and organizations in the community to request their participation. Many people stepped forward to offer their expertise, stories, and meaningful objects. Carrie spoke with academics such as Dr. Smith and Linda Allegro regarding their research. Ellen Flores served as an intern and translator for the project during a critical time. Yovana Medina and Saidy Orellana frequently consulted on the project; they offered advice and community introductions. As the project developed, it became apparent that the Guatemalan community in Oklahoma needed sustained attention. The local Guatemalan Consulate allowed Carrie to interview Ambassador José Rodríguez to learn more about the migration flows, culture, and demographics of the community. Francisco Santiago Rivas shared his experiences as a Puerto Rican and an Oklahoman. Chris Berry, Jamie Hinds, and Savanna Payne of Oklahoma City Public Schools’ Language and Cultural Services offered their expertise, contacts, and volumes of their book series authored by school-aged newcomers. Serena Prammansudh and Brenda Lozano shared their photos, stories, and suggestions as immigrant rights activists connected with Dream Action Oklahoma (DAOK). Raquel Astacio-Haley and teachers at Zarrow International School, a bilingual public school in Tulsa, donated objects from their birthplaces throughout Latin America. The trunk represents a true community effort.

To develop a strong timeline and create a more comprehensive narrative history to include in the trunk, the EDU team also began extensive newspaper research. Although there are no known Spanish language newspapers in Oklahoma until 1988 with the publication of El Nacional in Oklahoma City, English language papers did occasionally report on the Latino community. Fortunately, the Oklahoma Historical Society possesses the most extensive collection of community newspapers in the state providing an opportunity to research Latino history throughout the entire state of Oklahoma.

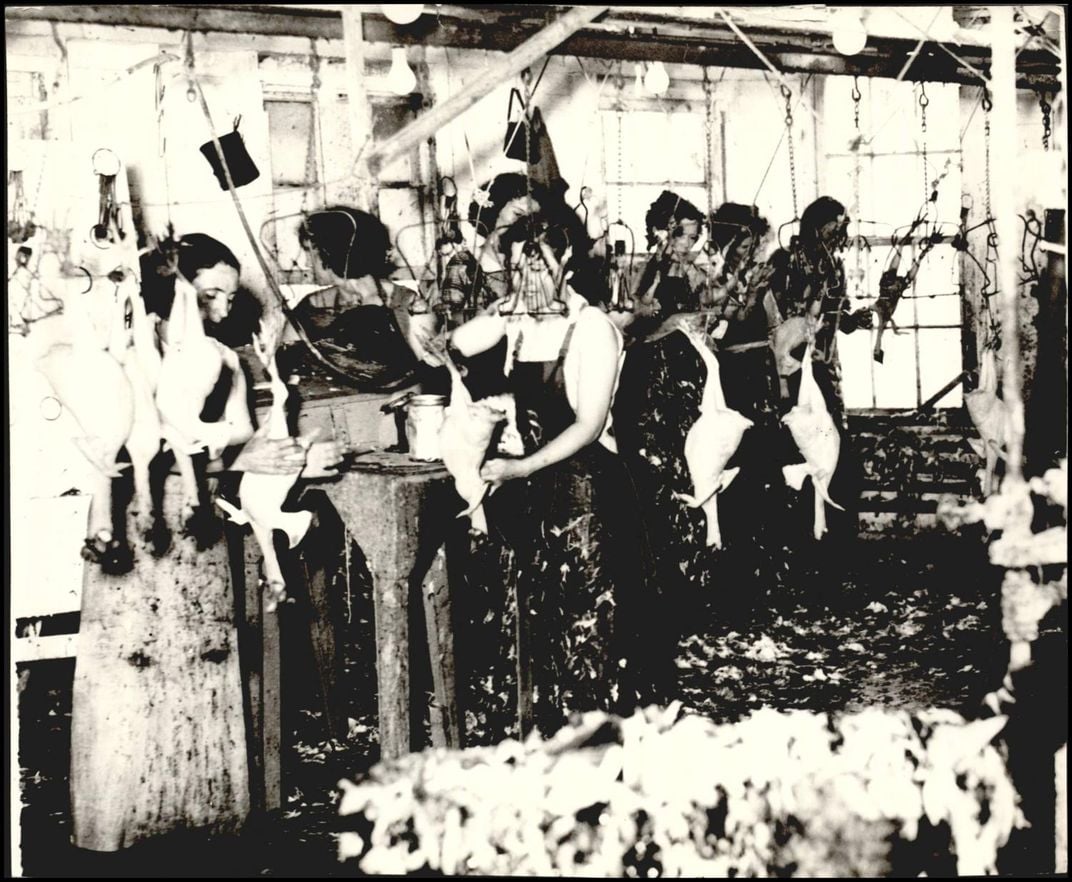

These newspapers revealed a great deal, such as the existence of a religious based organization called the Good Will Center that offered social services to Spanish-speaking packinghouse workers in Oklahoma City in the 1910s; evidence of a forced deportation of the Mexican residents of Bartlesville in 1914; and coverage of “A Day without an Immigrant” protests in Guymon in 2006. The largest newspaper in the state, The Oklahoman, also offered insight into Latino history in Oklahoma, albeit in an almost indirect fashion. Its annual articles on the Mexican festival in September offer evidence of a sustained Latino presence in Oklahoma from the 1930s onward, as do the advertisements for Mexican restaurants.

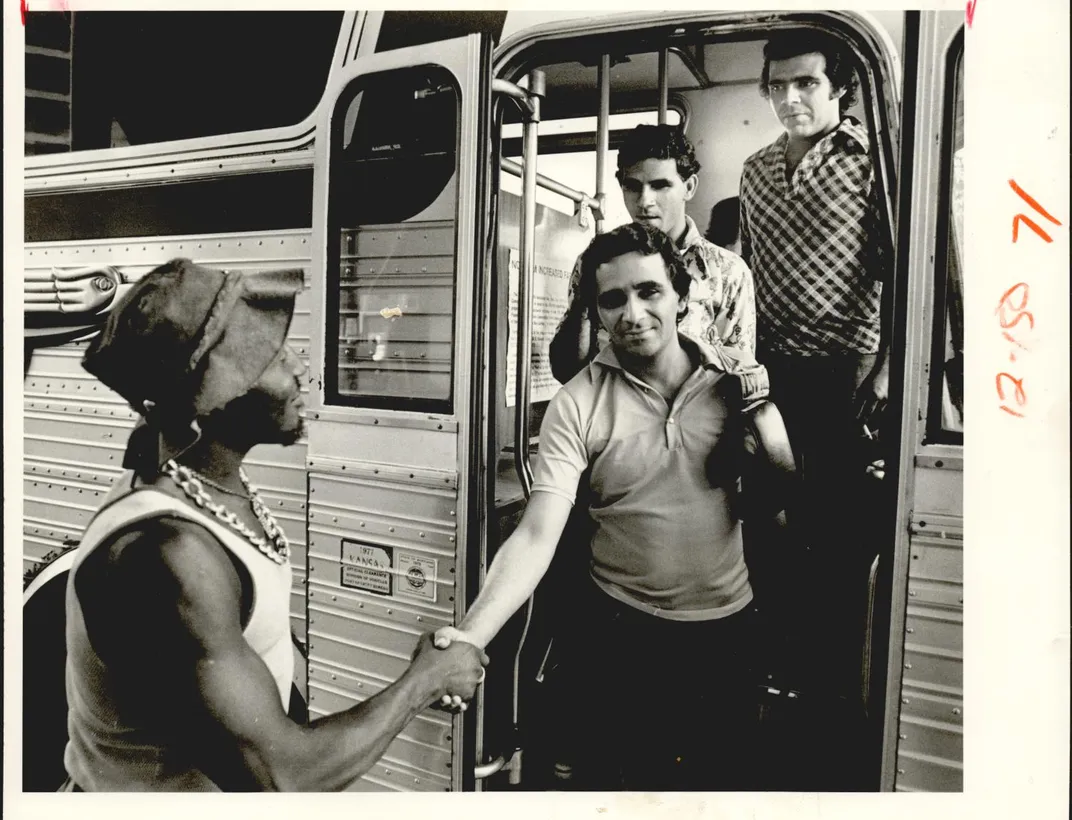

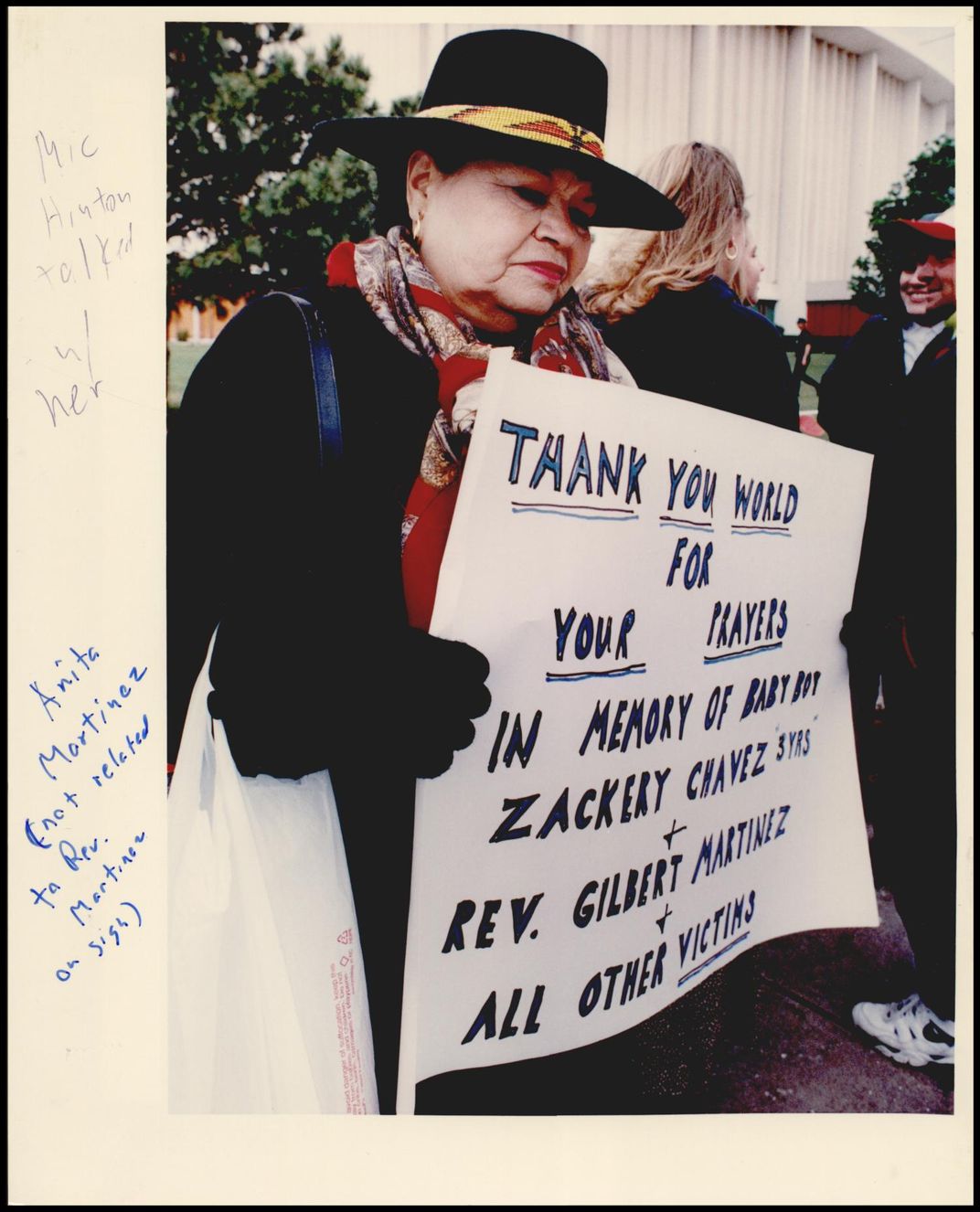

An optimistic article, “Mexicans Go to Homeland,” documents the beginning of a decade-long exodus of Mexicans living in the state and might be evidence of how repatriation worked in Oklahoma. The frequency and tone of the reporting in this newspaper also help document Latino history in Oklahoma. For example, the Oklahoman reported several times on the arrival and settlement of Cuban refugees from the early 1960s to the late 1970s in a positive, supportive context. In 1980, with an influx of immigrants from the more controversial Mariel Boatlift, reporters offered a more complex analysis of these refugees in the state. Similarly, reporting on the immigrant Latino population included a wide variety of themes in the 1970s and 1980s. By the 2000s, the Oklahoman focused on crime and politics in reporting on this group. For this project, they collected almost 400 articles which will be available to researchers working on these topics in the future.

An oral history project developed out of the lack of accessible primary sources from the perspectives of Latinos in the community. From the touching love story of Panamanian Susan Chambers, to the work of Bolivian Millie Audas and Colombian Yoana Walschap to build the international reputation of the University of Oklahoma, to the efforts of Mexican Javier Hernandez to become Oklahoma’s first undocumented lawyer, these oral histories are a starting point of recording the experiences and opinions of Latino individuals within the state.

Some of the stories, such as the efforts of Sister Joselita Allen facilitating Benvenuto Barrios’ immigration to Oklahoma, thus beginning the flow of Guatemalans to the state, are specific and serve to build the historical record. Other stories, such as Martha Fraire sharing about how much she loved when her father used to take their family of 11 to watch drive-in movies from across the street with no speaker, are timeless and universal. These interviews served as the basis for a small reader in the trunk called LatinOK: Individual Stories. This oral history project will continue, and the raw interviews will be available for future researchers in the John and Eleanor Kirkpatrick Research Center inside the Oklahoma History Center.

From this research, the OHC EDU Team created a 77-page history to share with educators and researchers in addition to hands-on objects, activities, videos, music, and books. Ideally, this trunk will be used in a variety of learning environments in the future, including newcomers’ classes, libraries, homeschools, and Oklahoma history classes. Additionally, because this is just a beginning, the research used to develop the project will be available to researchers interested in building these histories further as an ongoing research project.