SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM AND THE RENWICK GALLERY

John Baldessari: An Appreciation

Remembering the influential artist whose video works helped define contemporary art

His playfully profound video works helped define contemporary art

One of the giants of American art, both literally and figuratively, John Baldessari passed away just after the new year, on January 2, 2020. He was six foot, seven inches tall, had more than 200 solo exhibitions in his lifetime, and was a formative teacher to generations of aspiring artists from the 1970s until the 2000s. (For a super quick, super fun summary of his life, work, and sensibility, check out this video made when LACMA honored him in 2011).

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum, we have four videos from the 1970s by Baldessari in our collection, as well as a multi-part print piece from the 1980s. Each in its own way suggests the playful, pedagogical approach he took to looking, thinking, and creating as well as the recurring sources of inspiration within his practice.

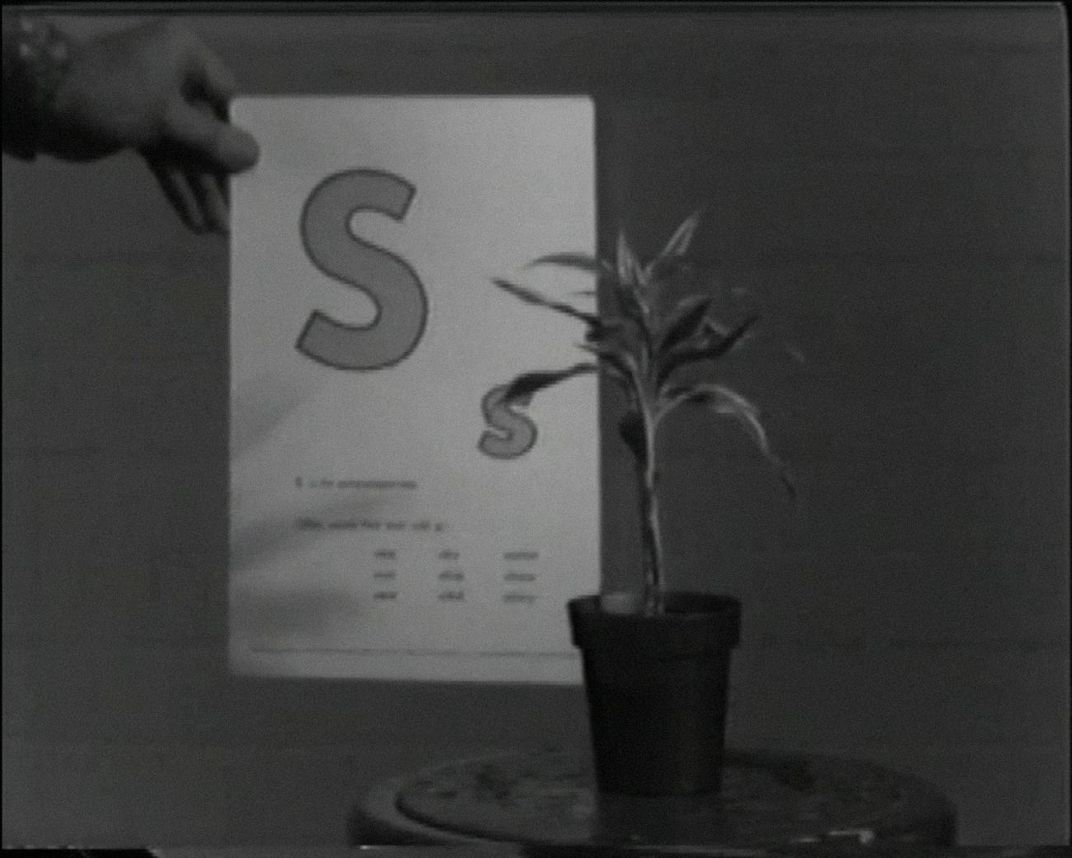

In the 1972 video, Teaching a Plant the Alphabet, a static camera shot opens on a humble potted houseplant. It sits on a table with a nondescript brick wall behind it. After almost thirty seconds of silence and stillness, a hand holding a paper printed with “A”, “a” and several small words (likely starting with the letter A but hard to read), enters the frame from the left. At the same time, a man’s voice starts intoning “aaayy, aaayy, aaaayy…” for another thirty-odd seconds. Then the hand and paper are withdrawn, there is a pause, and the same sequence is repeated, instructing the plant on the sounds, shapes and uses of the letters B through Z. This takes approximately eighteen minutes. After a final long pause, the sound cuts out and the tape ends. Described as a “rather perverse exercise in futility,” this piece is also a perfect introduction to Baldessari. The banality turns in on itself and the viewer becomes transfixed by the artists unwavering commitment to this thankless task. The droll, uninflected presentation becomes a humorously literal exploration of complex theories about how meaning adheres to abstract shapes and sounds to form language. And finally, it emphasizes teaching and language as imperfect modes of transmission and translation that, nevertheless, shape how we engage and understand the world around us. As Baldessari himself noted, “When I think I’m teaching, I’m probably not…When I don’t think I’m teaching, I probably am.”

In the subsequent years, language, teaching, and the relationship between images and ideas would remain central to Baldessari’s practice. Two later works in our collection show how this interest intersected with film and pop culture—in the 1973 video Ed Henderson Reconstructs Movie Scenarios, Baldessari asks his student to looks at stills taken from obscure movies, and imagine what the films might be about. As you watch, you are likely to find yourself playing along—and realizing how much inference comes not just from what is in the picture, but from cultural tropes learned over years of watching Hollywood films and seeing certain characters and stories told over and over. Baldessari’s Black Dice from 1982 takes up this game in print form, slicing a still image from a gangster movie into nine parts. Each of these sheets is somewhat abstracted but with visual clues remaining. The viewer is encourage to try to reassemble them in their mind and extrapolate a narrative from there—Baldessari instructs the museum to display the original photograph alongside the prints, presumably to help viewers puzzle this out.

Shortly after this, in 1985, Baldessari struck on what would be the most visually iconic strategy in his work—affixing bright colored circular stickers onto photocollages to obscure the faces of the actors, so their identities wouldn’t be the focus of the composition. These experiments would quickly grow, forming the basis for monumental, multi-panel photographic juxtapositions of movie stills with vinyl and paint interventions—the visual equivalent of a complex sentence, requiring extensive parsing and interpretation. (They also inspired the delightful, crowd-sourced Instagram @BaldessariYourLife, started by artist Steven Wolf, which will repost submitted photos with signature dots added.)

Nam June Paik, another artist central to SAAM’s collection, apparently gave Baldessari one of his favorite compliments when he said, “What I like most about your work is what you leave out.” By creating pockets of mystery in the fabric of the everyday, Baldessari’s art leaves space for the viewer, not only to attend to the process of meaning-making in the gallery, but equally in their everyday engagement with a world of images. Perhaps like a lesson from a houseplant, the inanimate work becomes a teacher, training us how to see and speak anew.

Coda:

While an obituary in the New York Times used to be my measure of lifetime achievement (and Baldessari got not one but two!), I now think the kind of endless scroll of individual online testimonials that have flowed for this towering figure with a huge heart is a bigger sign of a life well-lived. Even more touching is how many come from former students, mentees, studio assistants attesting to his generosity of spirit and wisdom…and how many of those on Instagram come from younger feminist, queer and/or artists of color, who he supported at critical moments in their education and careers.

May he rest in peace while his work continues to blaze a trail for future generations. Did I mention he lit a decades’ worth of painting on fire and baked them into cookies that were acquired by the Hirshhorn? To learn more, read Stale Cookies in a Jar.

I think my greatest regret now is only having known Baldessari through his art.