SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM AND THE RENWICK GALLERY

Level Up: Playing to Document and Preserve Video Games

Ever wonder what it takes to conserve and preserve video games? Our collections care initiative fellow at SAAM tells us how.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum has been dedicated to exploring video games as an art form ever since our groundbreaking exhibition, The Art of Video Games, in 2012. Earlier this month we held our annual SAAM Arcade online where we honored the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, granting women suffrage. Ever wonder what it takes to care for a digital work of art? Shu-Wen Lin, collections care initiative fellow at SAAM, shares her insights and expertise.

When my friends see me play video games, they all say the same thing: “You are not an experienced gamer—you tilt your whole shoulder with the controller, as if it would help you jump higher.” They are right. I grew up watching my neighbor’s older brother playing Nintendo, and I have not, until today, passed the first level of Super Mario. You can imagine my surprise that my role as collections care initiative fellow for time-based media has led me to study preservation techniques for video games.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum currently has three video games in its time-based media art collection. Like all technology-based works, technological change and platform obsolescence pose preservation challenges. SAAM’s Curatorial and Conservation departments have teamed up to address the entire collection lifecycle—acquisition, conservation, preservation, and exhibition—and proactively develop strategies. So how do we go about documenting and preserving video games?

Emulators can mimic the behaviors of old video game consoles and allow gamers to play vintage games on contemporary computing devices. For this reason, it has been adopted by the digital preservation community. Although SAAM exhibited two video games in the Watch This! Revelations in Media Art exhibition, the museum does not have documentation for the accurate game speed, visual effects, and element behaviors for either. Recording various scenarios is critical–not only can we fully contextualize the audiovisual and gameplay experience, but the media conservator needs these to evaluate any preservation or emulation results in the future.

We started with Halo 2600 developed by Ed Fries. It is a demake (a video game created in older graphical style for an older system) released in 2010 for Atari 2600, a popular video game console during the 1970s and 1980s. Harnessing the creativity prompted by technical limitations and the nostalgia for Atari-aesthetics, Fries reimagines the cutting-edge visuals and complex narratives of the 2000’s Halo franchise to fit the drastically smaller memory capacity of early game cartridges. Since Halo 2600 was released for a long- discontinued console, most gamers might have first played the game on the emulators. Therefore, we decided to record the playthrough both on the emulator and the artist-intended original console.

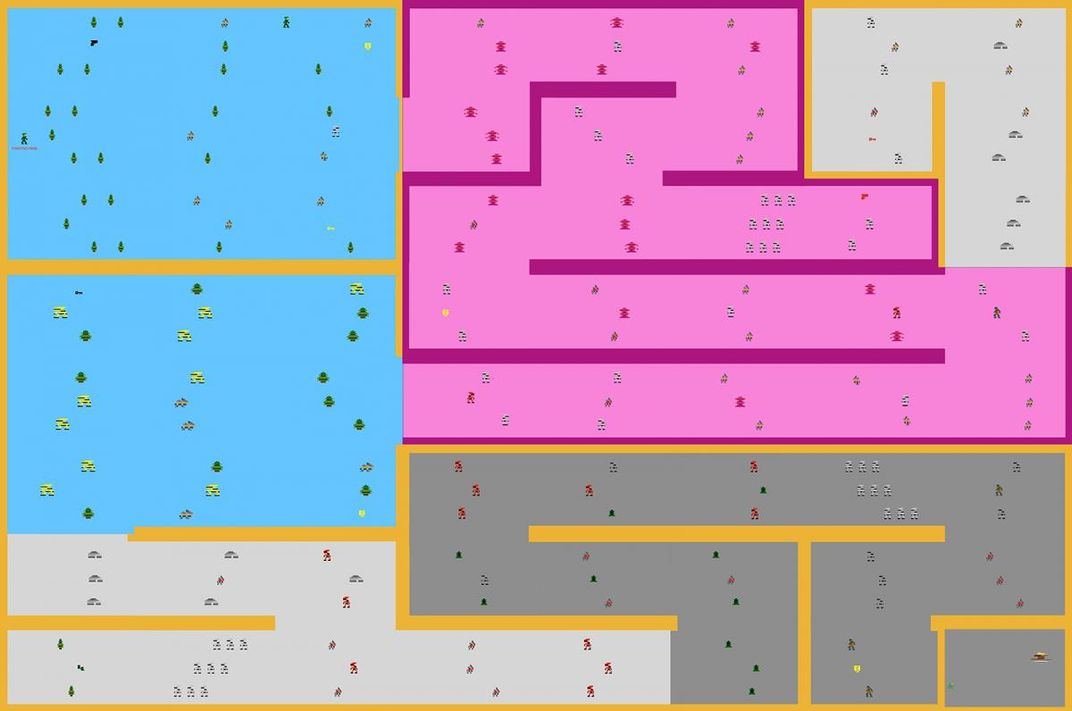

Immediately, I ran into my first obstacle: how can I evaluate the success of an emulation? First, I found three available Atari 2600 emulators and each one rendered the game with slightly different colors, position of elements, and element behaviors. Second, there is no record in our system about the total game levels, nor do we have a game map that shows every scene with all elements in each level throughout the entire game. Since I am not an experienced gamer, I am nowhere close to finishing the game in order to learn if every level of the game can be fully presented.

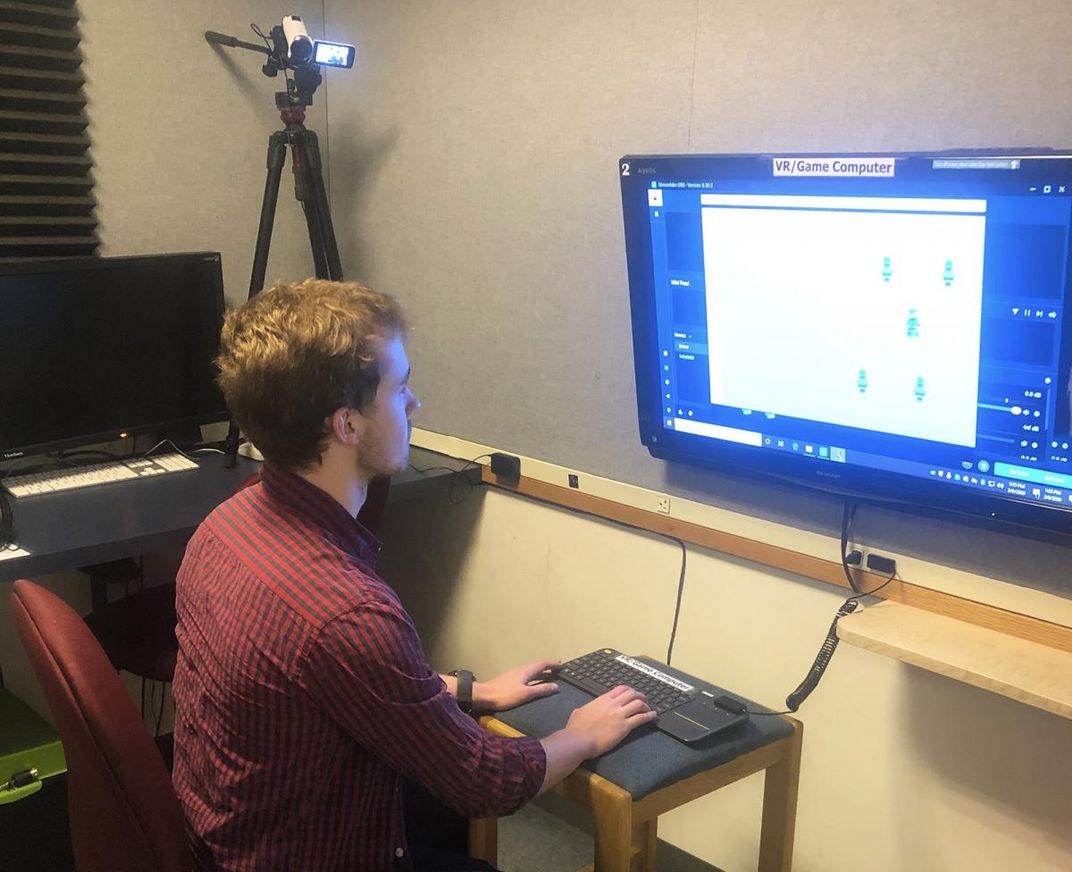

To solve these issues, we reached out to the game’s developer Fries to locate his preferred emulator and gather questions for a gamer questionnaire. Meanwhile, SAAM’s team—Curator of Time-based Media Saisha Grayson, Media Conservator Dan Finn, and I—collaborated with Amanda Phillips, assistant professor in English and film and media studies at Georgetown University, for a class project.

With Phillips’s help, we partnered with Georgetown’s Lauinger Library to host gameplay recordings with students over an open-source emulator in March. Students at all levels of gaming experience participated in the project. During the recording, each student was given 30 minutes to curate their experience. They were encouraged to narrate their thought process about their interpretation of elements as well as their gaming strategies. In addition to a full screen capture of the gameplay itself, we set up a separate camera to capture students’ interactions with the game and the gaming device. After the recording, every student filled out the gamer questionnaire which will lay the groundwork for an upcoming artist interview and for assessing the success of various emulations in conveying the intended experience.

Additionally, we were able to use the recording footage to put together a complete game map of Halo 2600. Along with the recordings, it can be used as a reference in the future to evaluate the emulated results.

We are planning to interview Fries and have him perform the gameplay recording at SAAM’s media conservation lab. We also will invite students to come back and play on an original cartridge running on the classic Atari 2600 hardware. This body of documentation will provide crucial context to future museum staff and visitors about how these games were used and enjoyed, if they become unplayable for any reason, and will help guide future preservation and display decisions.