SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM AND THE RENWICK GALLERY

Chicano Graphic Arts and the Making of the Landmark Exhibition “¡Printing the Revolution!”

Exploring the origins of the exhibition that combines innovative printmaking practices with social justice

Curators E. Carmen Ramos and Claudia Zapata discuss ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now

SAAM’s landmark exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, explores how Chicanx artists have linked innovative printmaking practices with social justice. In the first of a two-part conversation, join E. Carmen Ramos, exhibition curator and acting chief curator at SAAM, and Claudia Zapata, curatorial assistant for Latinx art, as they discuss the origins and importance of the exhibition.

Carmen, what prompted the development of the ¡Printing the Revolution! exhibition?

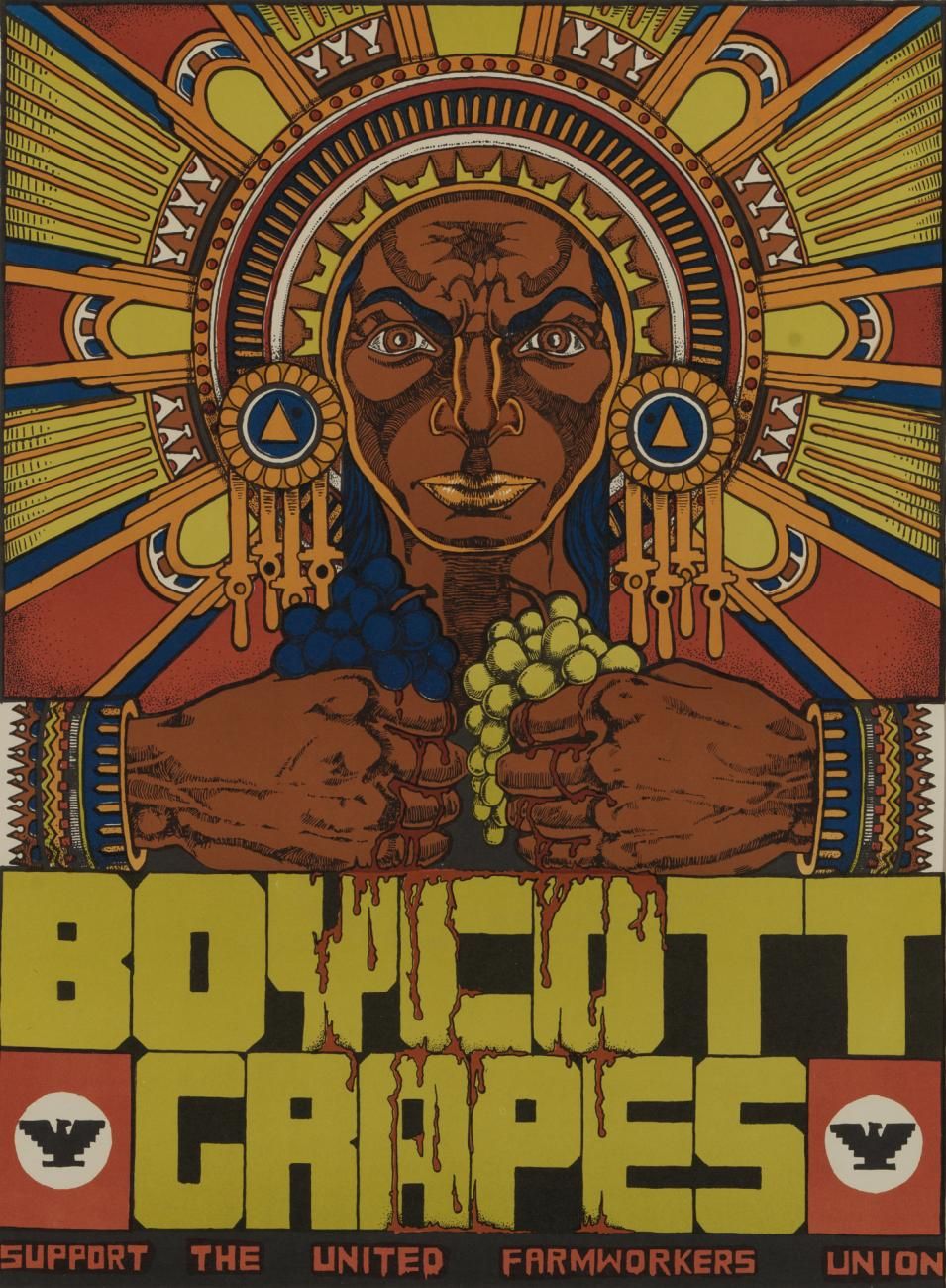

Ever since I arrived at SAAM, I was aware of a special gift we received from the foundational scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, who has devoted much of his career to the study of Chicano culture. In 1995, he donated sixty civil rights–era prints to SAAM, which he had collected over the course of his intellectual activism, as I like to call it. It was an important gift that offered a window into how Chicanos used printmaking within a multifaceted civil rights movement that emphasized political activism and cultural affirmation. This exhibition emerged out of a goal to call attention to this significant graphic movement, which sadly remains excluded from most histories of US graphic arts, and to also bring our collection up to date by expanding the view to include artists working today.

The title was inspired by Gil Scott-Heron’s recording “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (1971), often considered the first rap song, which suggests that calls for social change may not be captured by mainstream media. Activist artists had to find other ways to communicate with the public. For Chicanos, printmaking was an affordable, culturally resonant, and generative vehicle that allowed artists to address a public, especially a Chicano public, that was coming into awareness of itself. I also liked invoking the notion of “revolution,” a widely circulating term in the 1960s and 1970s. For many, revolution did not mean armed rebellion but rather, a new way of seeing the world centered on social and individual transformation. The exclamation points convey both the urgency of this initial moment, and the visual and conceptual dimensions of many of the featured works, which demand to be seen and unpacked.

Claudia, I really wanted you to join the curatorial team because of your expertise in Chicanx art. You bring so much knowledge to the table. Given the demographics of the East Coast, Chicanx art is not well known in this part of the country. Why did you want to work on this project?

I worked with Mexic-Arte Museum’s vast graphics collection, archived the Serie Project residency, and my dissertation looks at exhibitions featuring Chicano art, so, I have been steeped in this content. Throughout these endeavors I have encountered polarizing interpretations of Chicano art: some argue it is dead; others say it is in a “post” period; others want it to exist in a very specific conceptual framework; and then there’s reality. It’s also unique for there to even be a major Chicano exhibition; aside from the recent Pacific Standard Time collaborations, exhibitions such as these are quite rare. I was eager to see what SAAM’s stance would be on interpreting this material at a national level, versus regional or collector-specific. Given Tomás Ybarra-Frausto’s donation in 1995, SAAM still had 25 more years of Chicanx graphic arts production and a whole new generation of artists to recognize. The importance of an exhibition such as this, particularly at SAAM, is the institution’s claim that Chicanx art is American art and thus is the steward of this artistic practice. In supporting your vision for the exhibition, SAAM now has the largest museum collection of Chicanx graphics on the East Coast. Other major museum collections are in Texas, California, and Illinois. By taking on this task, SAAM sends a wider message to major arts institutions that Chicanx art is significant to telling the US story and is an integral part of art history.

Carmen, what did you want to convey with the phrase “rise and impact” in the exhibition subtitle?

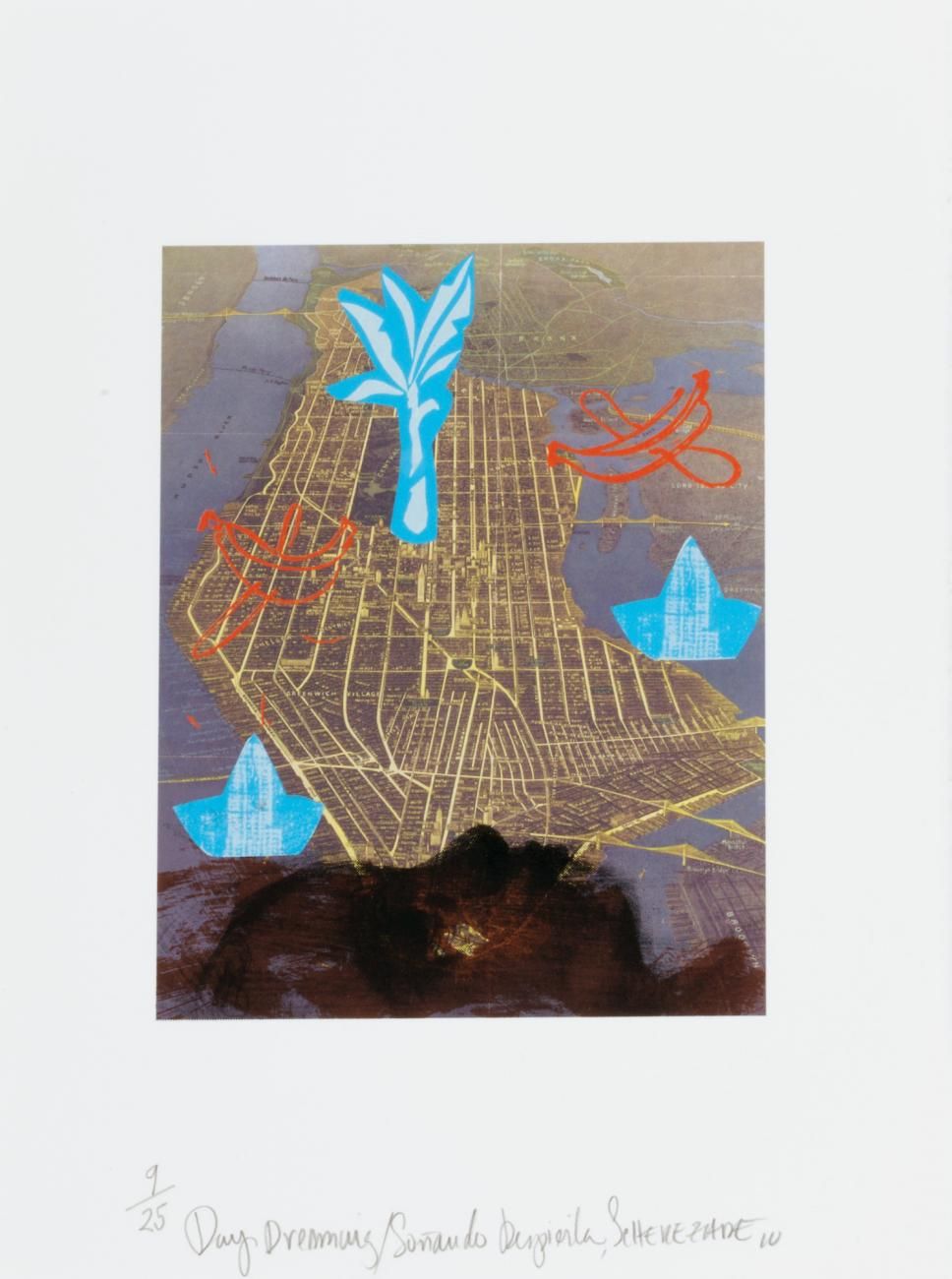

A common misconception of Chicano graphics is that it is a fossilized aspect of the historic civil rights era of the 1960s and 1970s. What we saw when we dug deeper into this field is that Chicanx graphics artists continue to thrive and produce exciting, relevant work. In part this has to do with the ongoing struggles of our world and the ways in which graphics is still an especially productive medium to engage contemporary society. People in this country, especially BIPOC people, are still fighting the same battles. Our immigration debates ruminate on the same issues that have been around since the 1970s. Artists in the 1960s and 1970s were creating works about police abuse and brutality, as they are today. And they are still calling for the wider society to value Latinx cultures and people in all of their complexities. The word “rise” pays tribute to that groundbreaking civil rights –era generation. The word “impact” expands our focus to the enduring legacies of Chicano graphics and the multifaceted ways those early years have informed the art of today.

Our research documented a web of relationships between generations. For example, in the 1990s, Juan Fuentes mentored Jesus Barraza at the Mission Cultural Center in San Francisco. Jesus and his partner Melanie Cervantes, who form one of the most prolific Chicanx graphics collectives today, Dignidad Rebelde, have worked collaboratively with iconic figures like Malaquias Montoya and Rupert García. “Impact” also conveys how the Chicano graphics movement is both influential and inclusive. Sam Coronado founded The Serie Project, a print residency program in Austin, after his experience as an artist-in-residence at Self Help Graphics in East Los Angeles. Our exhibition allows us to call attention to how artists from other communities—Asian Americans, progressive white artists, other Latinx artists—were active in Chicanx print centers and other cross-cultural projects. The political and artistic ethos of these centers supported and shaped artists’ works. As Ecuadorian American artist Sandra Fernández reflected: “The Serie Project was pivotal to my growth and trajectory as an artist. It changed my life.” This hasn’t been called out in previous exhibitions of Chicanx graphics. It’s important to acknowledge this wide historical impact.

Claudia, the term Chicano can be employed in several variations (such as Chicanx, Chican@, Xicanx) with multiple objectives for each term. Can you discuss the term’s resilience?

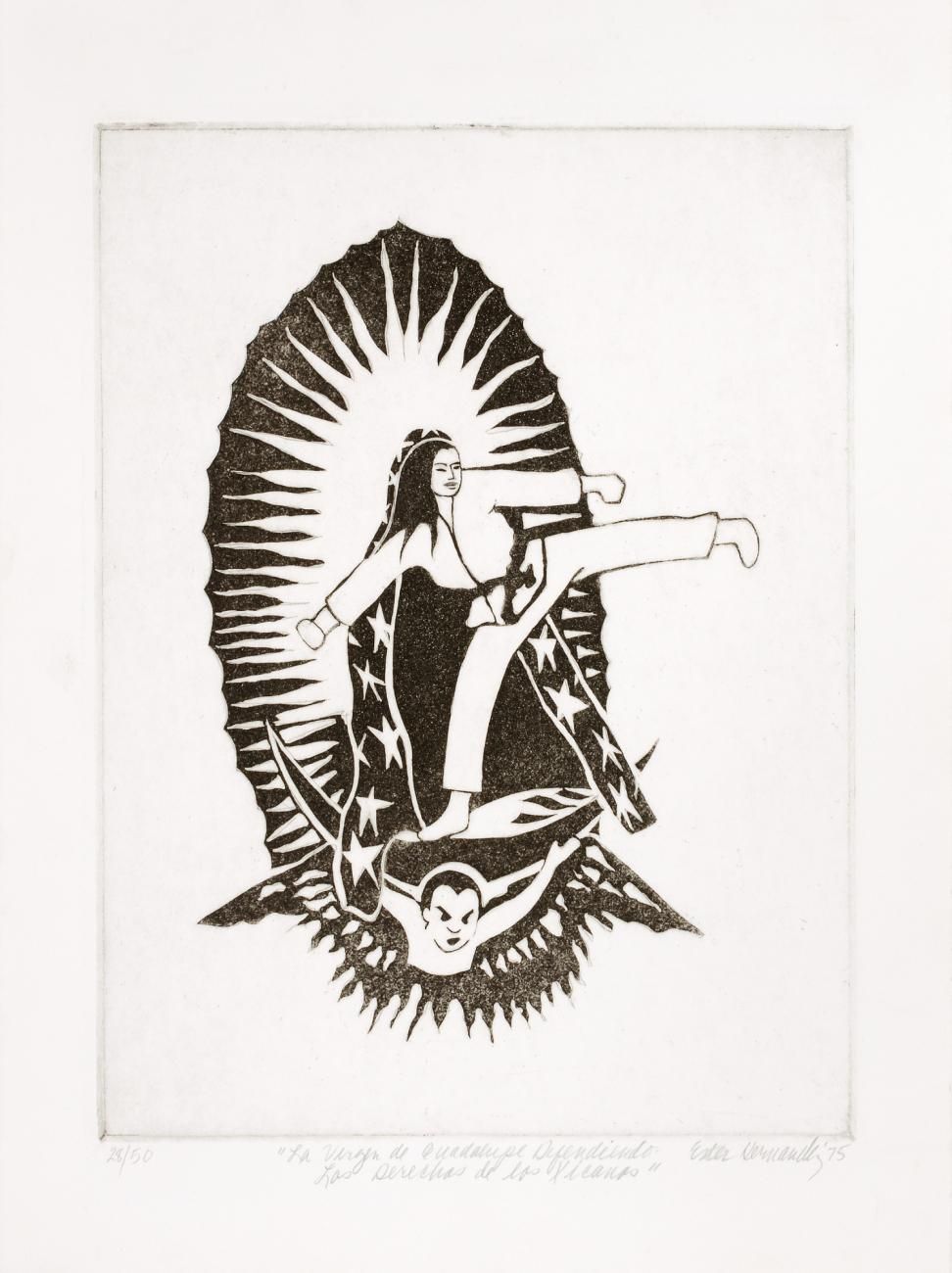

The term Chicano has multigenerational appeal, and its ability to be altered per the user’s theoretical desires is a testament to its resilience and applicability. A foundational definition is by the slain journalist Rubén Salazar: “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself.” The often-quoted definition highlights the Chicano movement’s challenge to white supremacy and the decolonial consciousness of those employing the term. Yet, it also reaffirms its limitations by reducing the Chicano framework to an engendered, Mexican American male perspective. Feminists within the movement decried gender inequity and countered with the feminine ending Chicana. There is a whole slew of canonical Chicana feminist writings that are part of the interdisciplinary sources informing visual artists’ work, such as Alma Lopez’s Our Lady, which was inspired by Sandra Cisneros’ essay “Guadalupe, the Sex Goddess.”

Indigeneity is a major theme within the movement, with scholars looking to the ancient world. Author Ana Castillo’s term Xicanisma takes the “X” prefix from the Nahuatl language in order to broaden Chicana feminism. For example, featured Bay Area collective Dignidad Rebelde specifically cites Xicanisma as a theoretical framework informing their artistic practice in their biography. Xicanx, which combines the Nahuatl, Chicana feminist nod with a gender-neutral and non-binary suffix, is the latest conceptual reinterpretation, and one with which featured artist Michael Menchaca aligns. I refer to Chicano as an open-source term, recalling the practice within software development that allows the public to modify and improve the source code based on a shared value system of community-driven betterment. The modification of Chicano as a term and as a set of decolonial principles will only improve with the contribution and acknowledgement of the diverse communities that comprise it. This recurring change challenges a preconceived notion of control, or an ownership of this movement by any one group of people. Instead, it opens and reifies the initial objective of the term’s inception: to decolonize one’s mind.

Additional images and commentary about artworks included in the exhibition can be found in our online gallery. On Tuesday, January 26, at 6:30 p.m. ET, join Juan Fuentes, artist; Dignidad Rebelde (Jesus Barraza and Melanie Cervantes), artists; and Terezita Romo, art historian, curator, and a lecturer and affiliate faculty member at the University of California, Davis for on online program “Cross-Generational Mentorship and Influence.” It is the first in a five-part online conversation series that examines Chicanx graphic arts and how artists have used printmaking to debate larger social causes, reflect on issues of their time, and build community.