SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM AND THE RENWICK GALLERY

Chicanx Queer Visions: Fighting for Change and Exploring Identity

Artists in SAAM’s exhibition ¡Printing the Revolution! explore pressing issues of the LGBTQ+ community

Protests against police brutality define the history of the LGBTQ+ rights movement. Queer uprisings, including 1959’s Cooper Do-nuts Riot in Los Angeles and the 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Riots in San Francisco, punctuated the LGBTQ+ community’s resistance to police harassment, particularly of Black and Brown trans women. The turning point came on June 28, 1969, when bar patrons at the Stonewall Inn protested a police raid for six days. Now known as the Stonewall Riots, this pivotal event led to critical advancements in the gay liberation movement and the beginnings of annual pride celebrations of queer visibility and community solidarity. LGBTQ+ communities across the country celebrate June as Pride, a month-long commemoration of the Stonewall Uprisings and of significant queer individuals and radical histories. In celebration of Pride, SAAM highlights the queer and ally Chicanx and Latinx artists in ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now whose artwork directly addresses issues of social justice, cultural reclamation, and commemoration.

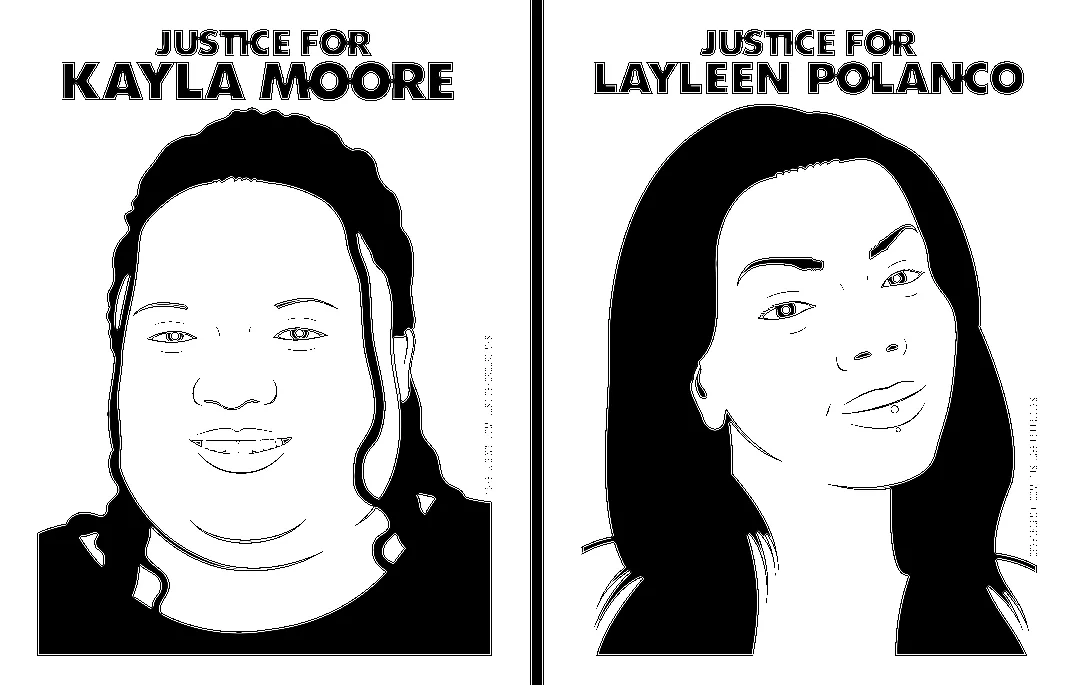

The struggle continues to this day; fatal violence against Black and Brown trans women is at a crisis level nationwide. Human rights organizations and many news outlets have an annual data tracker, cataloging the tragic murders of trans and non-binary people throughout the year. Artist Oree Originol’s commemorative portrait project, Justice for Our Lives, addresses the untimely death of many who have died at the hands of law enforcement, including Kayla Moore and Layleen Polanco. The deaths of these disabled trans women led to protests from their families and communities, prompting criticism of police and incarceration practices. Originol uses Moore’s and Polanco’s personal photographs as the basis for their portraits to memorialize them and demand justice.

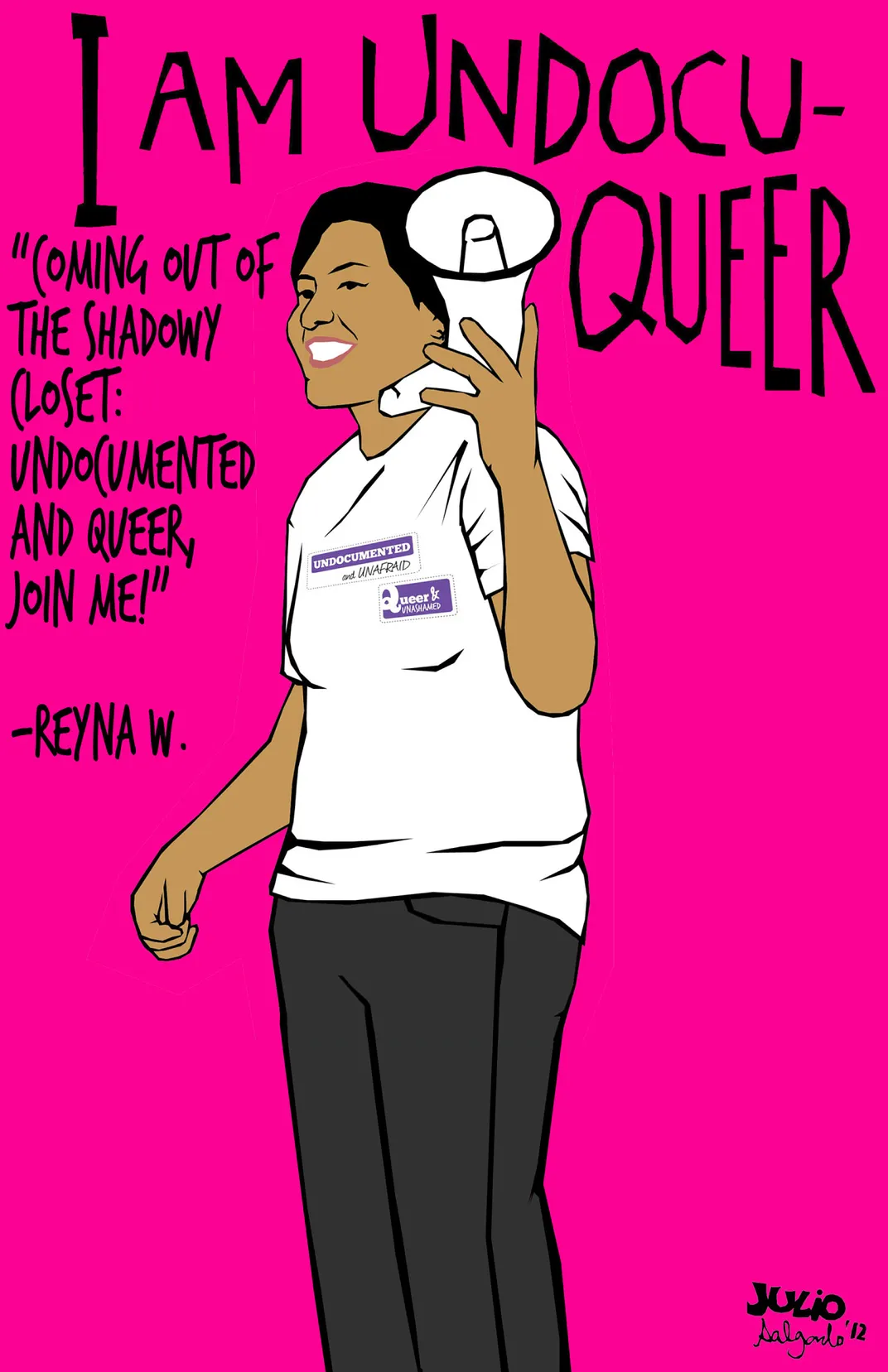

Mexican-born and queer artist Julio Salgado emphasizes the importance of intersecting identities within the migrant rights movement, addressing a community that is both queer and undocumented (undocuqueer) in his series, I am UndocuQueer. Working with the Undocumented Queer Youth Collective and the Queer Undocumented Immigrant Project (QUIP), Salgado used the microblogging site Tumblr to ask other undocuqueers for a photograph and a personal reflection on their intersectional identities. He then transformed these words and images into a colorful digital series to increase the presence of undocuqueers in the migrant rights movement.

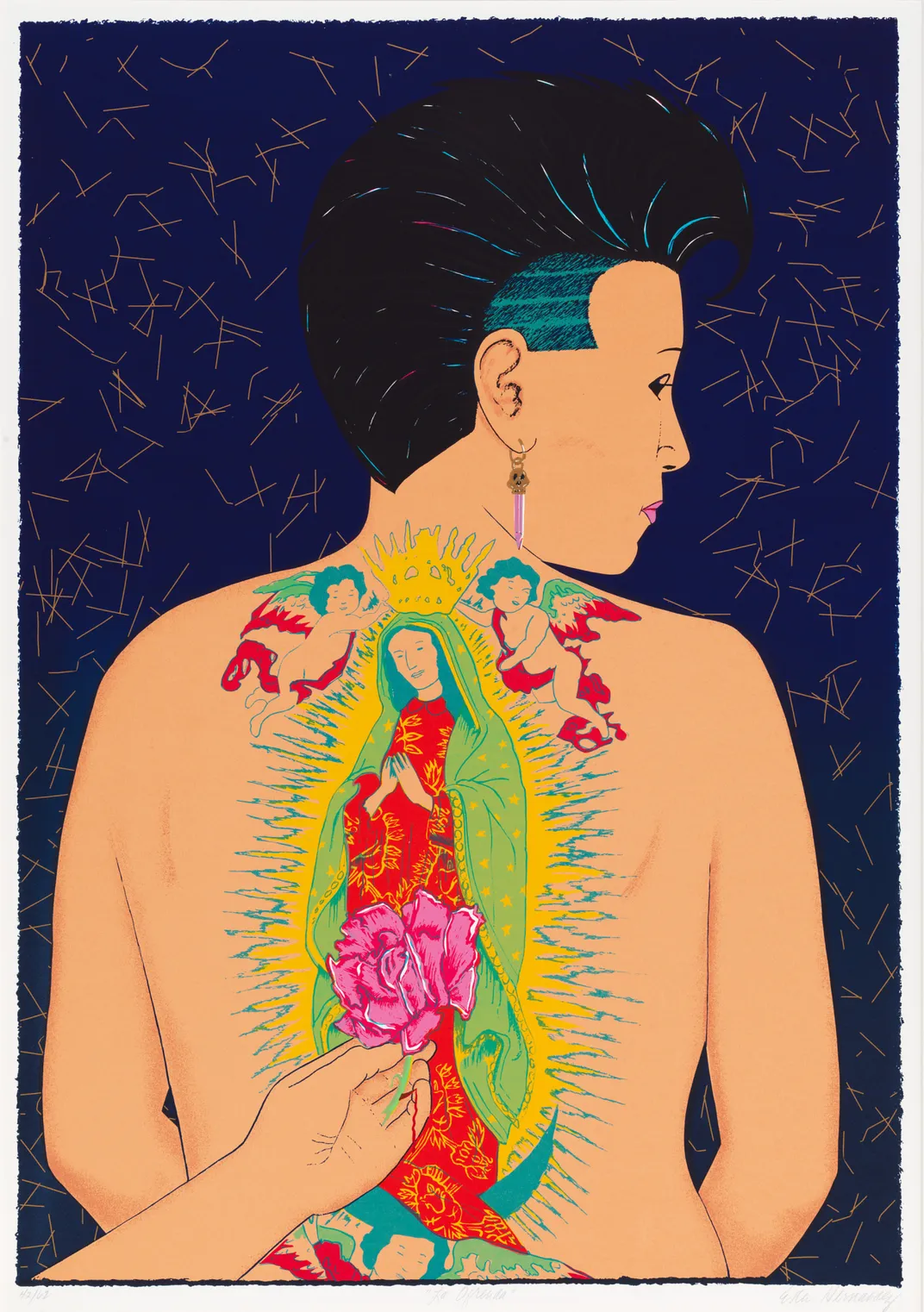

“Queering” or deconstructing fixed categories and perception challenges definitions of “traditional” and normal” cultural authority. Reclaiming the previous pejorative, “queer” has been an essential part of the LGBTQ+ rights movement. However, it is important to note that while some adopt its usage, many still are uncertain about its application. Queer readings embrace a unique approach to culture, and this new lens has been essential to Chicana lesbian artists and their reclamation of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Playing a critical role in Mexican Catholicism, the Virgin of Guadalupe is a canonical religious icon that continues to grow in devotion since the original 16th-century Marian image appeared to Juan Diego on a tilma, or cloak, at Tepeyac, a hill in present-day Mexico City. Chicana/Yaqui artist Ester Hernandez emblazons the Virgin on her then-partner’s back in the 1988 screenprint, La Ofrenda. The delicate scene includes the artist’s hand offering a rose to her partner, highlighting the intimacy between the women. Informed by tattoo culture, Ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock print style), and henna dye body painting, Hernandez positions her tattooed lover’s back as a new, queer recipient of this traditional image. La Ofrenda has become a lesbian iconic image since gracing the cover of Carla Trujillo’s popular book, Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About in 1991.

Pride month observations rely on both celebration and community reflection. The social issues and the cultural reflections by queer artists, as featured in ¡Printing the Revolution!, present the intersectional themes and strategies Chicanx and Latinx queer artists use to empower the oppressed, build community, and acknowledge the diversity of their lived experiences.