Carving Space for Diversity in Skateboarding

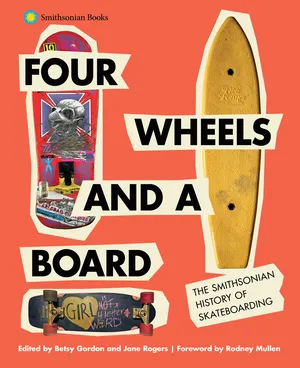

Explore the last decade of skateboarding and its push for inclusivity and diversity with this excerpt from “Four Wheels and a Board: The Smithsonian History of Skateboarding.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/04/07/040796f5-c234-473a-98bb-16762ed06de4/wcmx_wheelchair.jpg)

Paralyzed below the waist, Aaron “Wheelz” Fotheringham founded WCMX, or wheelchair motocross, a sport that combines tricks adapted from skateboarding and BMX that are performed in skateparks. He used this WCMX wheelchair, designed by Mike Box for jumping big ramps, to kick off the 2016 Paralympic Summer Games in Rio.

Skateboarders with differing abilities joined the skateboard community in growing numbers in the 2010s as more skateboard competitions included adaptive events. Although adaptive skaters have been involved in competitions since the mid-1990s, the inclusion of skateboarding in the Olympics opened up more opportunities to compete. The 2021 Dew Tour, which featured Olympic qualifying events for the Tokyo Olympics, also featured a street and pool event for adaptive skaters. Whether riding a skateboard or dropping in with a wheelchair, adaptive skaters are growing in numbers and the skate community has welcomed their effort. And while they are still waiting for skateboarding events in the Paralympics, Oscar Loreto Jr., an adaptive skater, is an athletic director for USA Skateboarding and a vocal advocate for skateboarders with differing abilities.

While the latter part of the decade will be forever defined by COVID-19, many other major events left their mark. From 2011’s Occupy Wall Street, to the Women’s March and Charlottesville protests of 2017, to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, this was a decade of protest and outrage.

Skateboarding and skateboarders took notice and participated in these social justice movements, demanding change not only from outside systems and institutions but also from the skateboard industry itself. They urged their fellow skaters to participate in the national presidential elections. They directly challenged the pervasive myth that skateboarding was inclusive and welcoming, color and class blind. They revealed that racism, sexism, and homophobia had always been part of the industry and the culture, and although they had vacillated between covert and overt, they have been overwhelmingly tolerated.

While some argued that skateboarding mirrored the sexism, racism, and homophobia underpinning American culture, there was a notable disconnect and dissonance between what was happening in America and what was being seen and promoted within the skateboard community. Women around the world continued to garner significant achievements in the arts, sciences, and politics while remaining largely unacknowledged in skateboarding until recently. In Thrasher’s forty-year history, women have been featured on only four covers out of five hundred. That is less than 1 percent representation for half of the population.

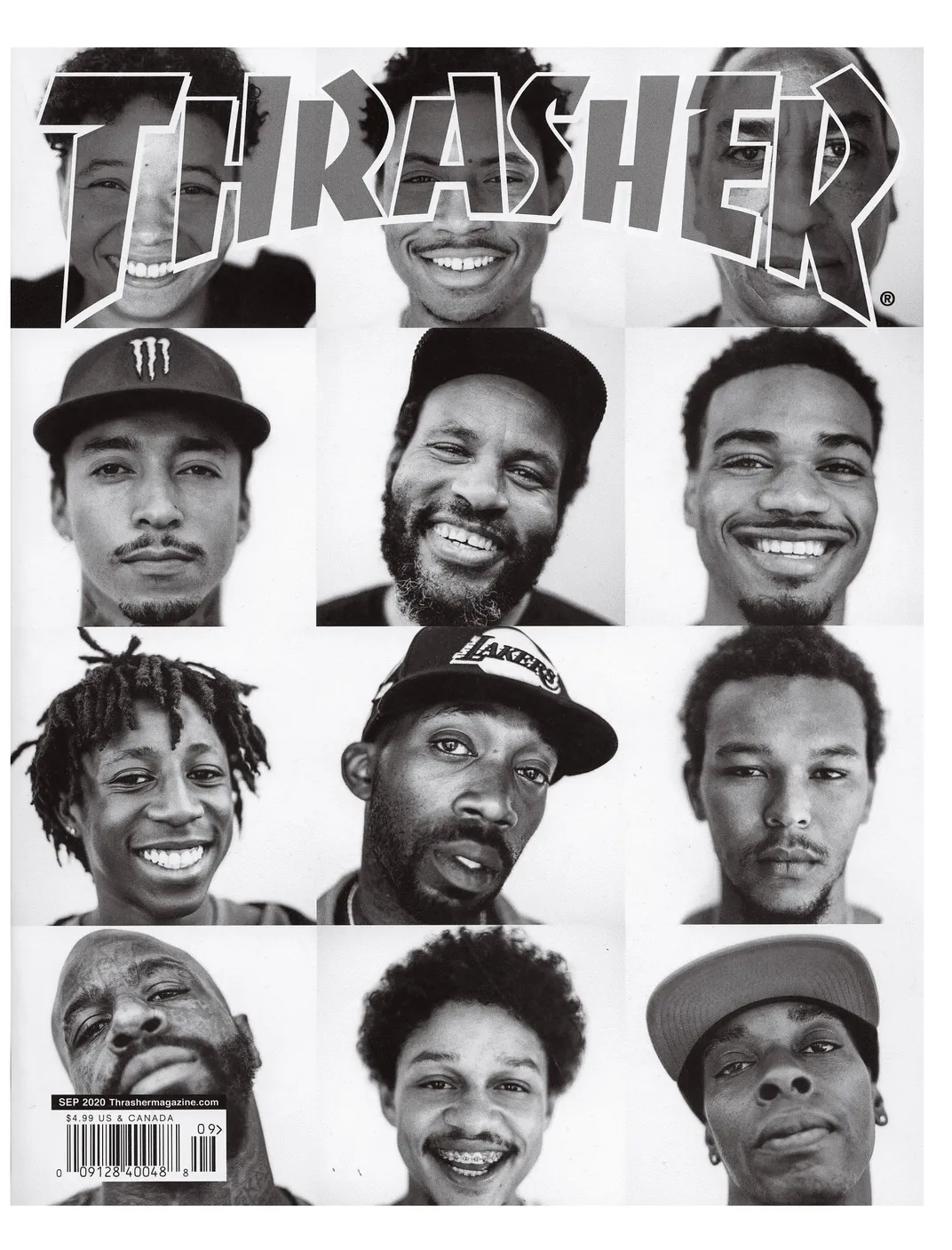

Recently, there has been a growing consciousness of how harmful the accepted paradigm has been and how long overdue accountability and apology are. In 2016, skateboarder Brian Anderson used a twenty-six-minute video on Vice Sports to come out as gay. In 2019, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, Bigfoot magazine published a groundbreaking article that addressed the occurrence of sexual abuse within the skateboarding community. Written by skateboarders Alex White and Kristin Ebeling, “Coping with Creeps: Concrete Action You Can Take” states unapologetically that “The hashtag lately has been #MeToo but it’s clear that it must be #All-In if we ever want things to change.” Shortly after the murder of George Floyd and subsequent BLM protests, Thrasher magazine published its September 2020 issue with thirty-seven images of Black skaters on the front and back covers. Guest editor Atiba Jefferson declared, “This issue is a celebration of one of many cultures that have made an amazing impact on skateboarding."

And then there was the Olympics. For much of this decade, the Olympics was promised and fought over. COVID-19 further complicated this. Skateparks were shut down and competitions—national and international—were canceled. The competition-based process of qualifying for the Olympics was placed on indefinite hold, and the 2020 Summer Games were postponed until 2021.

Marred by organizational missteps and delayed for a year by COVID-19, skateboarding nonetheless made its Olympic debut in August 2021. Although Team USA did not win the number of medals they hoped for, the team, which included two Black, one Native Hawaiian, and one gender-nonconforming member, represented the new, aspirational face of skateboarding—diverse and inclusive. For many, seeing the diversity of the Olympic skaters on an Olympic podium defined skateboarding as something they could participate in. In particular, many skateboard shops saw a noticeable increase in demand for skateboards from young women. The International Olympic Committee’s addition of skateboarding into the 2024 and 2028 Olympic Games seems to have cemented its future as an Olympic sport.

During this past decade, skateboarding found itself again in the vanguard of using social media and the Internet to create and distribute content. It redefined what it meant to be a skate brand, adding haute couture and pinball machines to its product drops. It advocated for social justice and appeared in university course offerings. As it enters its seventh decade, it is bound to reinvent, redirect, and readdress, exasperating some who will resist these changes as deviations from the “core” of true skateboarding. However, what seems to be at the core of skateboarding, no matter what decade, is polymorphism and creativity.

Four Wheels and a Board is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Four Wheels and a Board © Smithsonian Institution