Remembering Johnny Cash’s Activism 20 Years After His Death

While the country music star is beloved for his musical talents, he also used his fame to fight for prison reform and Native American rights

:focal(886x608:887x609)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ac/37/ac377891-f055-47b5-a1aa-8618b72ad40e/cash_receives_an_honor_from_a_tribal_elder.jpg)

© 2018 John R. Cash Revocable Trust

"He was willing and able to be the champion of people who didn’t have one.” That was how Kris Kristofferson characterized Cash after his friend and colleague’s death. For all of his musical accomplishments and contributions, one thing that distinguishes Cash from many other great artists was his genuine sympathy with and understanding of the underdog, and his consistent use of his platform to give a voice to the voiceless, led not by dogma but by simple human decency.

He was also drawn to stories of rebels, outsiders, and long shots, and used the materials as themes for songs. This, Cash believed, was not a unique position for him to take, but placed him in a true American tradition. “Our heroes in song were, for the most part, antiestablishment,” he once wrote. “We want to feel his pain, his loneliness, we want to be a part of that rebellion."

Some believed that this attitude tipped over into glamorizing the actions of criminals, but he pushed back against that interpretation of his own music, or of those who faced similar accusations throughout pop music history. “The biggest-selling song of the nineteenth century was a song about a bandit and an outlaw and a killer,” he said to me in 2001. “It was called ‘The Ballad of Jesse James.’ And those themes have carried through up until now.

“I watched Elvis go through it—people saying, ‘You’re leading our children to hell!’ I’ve been hearing it all my life. But I have yet to hear anyone take it seriously and actually shoot a man in Reno just because my song said so.”

For the liner notes to box set Love God Murder—a collection released in 2000 with three discs, each of them dedicated to one of the three themes in the title—Quentin Tarantino contributed his thoughts on the “murder” group. He called them “poems to the criminal mentality,” writing that “Cash sings tales of men trying to escape . . . but the one thing Cash never lets them escape is regret."

His own beliefs about crime and punishment manifested themselves most visibly, of course, in the concerts he played at prisons throughout his career. The public was made aware of these shows in the late 1960s, when he released the best-selling albums recorded at Folsom and San Quentin. But Cash had actually been playing for prisoners for many years at that point, and had performed at San Quentin as far back as 1958. And his concern went beyond just showing up for musical performances: In 1972, Cash testified at a US Senate judiciary subcommittee hearing on prison reform, offering his support for proposals to keep minors out of jail and to focus on rehabilitating inmates.

“I didn’t go into it thinking about it as a ‘crusade,’” he said. “I mean, I just don’t think prisons do any good. They put ’em in there and just make ’em worse.” He expressed his opinion about the prison system more succinctly to Robert Hilburn. “I don’t know how much good drudgery does anybody,” he said.

The most notable aspect of his prison concerts, in addition to the simple fact that he was prioritizing these appearances on his schedule, was the respect that he showed for the incarcerated. Merle Haggard, who was in the audience for one of the early San Quentin shows while he was locked up after an arrest for robbery, clearly remembered Cash’s onstage attitude.

“What stood out, even more than his music, was his demeanor,” Haggard later said. “He was a bit cocky and a bit arrogant . . . it seemed like it didn’t matter [to him] whether he was able to sing [well] or not.” The Country Music Hall of Famer recalled the concert as something that “may have been the first ray of daylight I had seen in my entire life.” (In another interview, though, he made sure to point out the limitations of Cash’s identification with prisoners—“Johnny Cash understands what it’s like to be in prison,” he said, “but he doesn’t know.”)

In 1973, Albert Nussbaum—once on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list for bank robbery—wrote an account of Cash’s appearance at Leavenworth for Charleston, West Virginia’s Sunday Gazette Mail. He focused mostly on the effect that Cash had simply by acknowledging the humanity of those behind bars. “We came because we care,” Nussbaum quoted Cash telling the crowd. “We care. We really do. If there’s ever anything I can do for you all, let me know somehow, and I’ll do it.”

The convict described how Cash would “handle [his] guitar as though it were a weapon,” and how the jail population’s connection to “Folsom Prison Blues” was so strong that most of them were overcome. “It captured our own feelings so exactly that our roar of approval completely drowned out the music,” wrote Nussbaum.

The other cause that Cash pursued over the years was his commitment to Native Americans. As far back as 1957, he had written a song called “Old Apache Squaw,” after which he “forgot the so-called Indian protest for a while. But nobody else seemed to speak up with any volume of voice.”

The advent of the folk movement, though, lit a fire under Cash to speak his mind on the treatment of Native Americans . “Johnny wanted more than the hillbilly jangle,” said Peter La Farge, the Native American songwriter who would become a key collaborator during this period. “He was hungry for the depth and truth heard only in the folk field.”

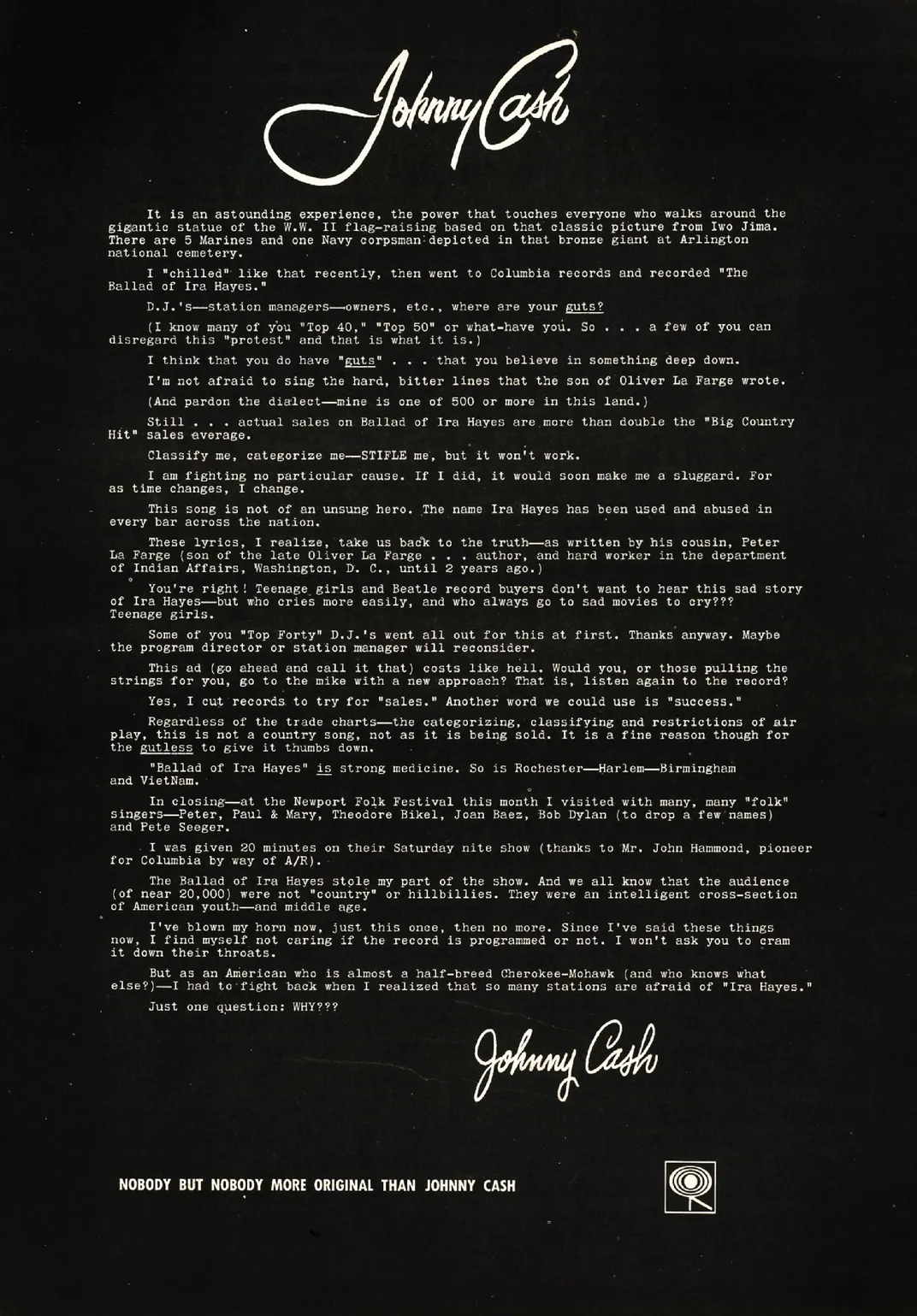

This led, most notably, to the Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian album in 1964, and his battle for acceptance of the La Farge-composed single, “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.” The project faced genuine opposition from Cash’s label and from the country music establishment, with one journalist even urging him to leave the Country Music Association, on the grounds that "you and your crowd are just too intelligent to associate with plain country folks, country artists, and country DJs.”

The hard-fought success he ultimately achieved with “Ira Hayes” was hardly the end of his involvement with Native American issues. In 1966, in recognition of his advocacy, Cash was adopted by the Seneca Nation's Turtle Clan. In 1968, he performed a benefit concert at the Rosebud Reservation, close to the historical landmark of the massacre at Wounded Knee, to raise money to help build a school.

The 1969 documentary Johnny Cash: The Man, His World, His Music includes footage of him singing “Ira Hayes” at the Rosebud Reservation’s St. Francis Mission school. The elders bless him in a ceremony, reciting “Oh, great spirit, watch him and watch over him,” and he recounts his feelings while visiting Wounded Knee—“such a mystical air hung over the place.”

In 1970, Cash recorded a reading of John G. Burnett's 1890 essay on Cherokee removal for the Historical Landmarks Association in Nashville, and on The Johnny Cash Show, he told numerous stories of the mistreatment of Native Americans , both in song and through short films, such as the history of the Trail of Tears. As late as the 1980s, he played at California’s D–Q University, one of the first tribal colleges in the United States.

Where did this passion for the Native American cause come from? Cash sometimes toyed with reporters by referring to his own Cherokee heritage, but there was no truth to that tale. As a student of history, proud of the research he did on his thematically based albums, he clearly saw the injustices that had been done to his country’s indigenous people. Maybe his own upbringing on a farm, and especially in a cooperative community, gave him a different relationship to those who had been displaced from their land, from the resources and opportunities to thrive by their own labor. As with his work on behalf of prisoners, maybe Cash just liked the idea of being able to speak up for those who he felt were misunderstood and misrepresented to the general public.

He was always adamant that his social efforts were neither political nor partisan. “I don’t think it would be fair for me to campaign for a presidential candidate and try to influence people that way,” he told Patrick Carr in 1976. “That’s important stuff and big stuff and I don’t think I’ve got a right to exercise any such control over the people.” In fact, for all his opinions and stances, Cash never voted in an election.

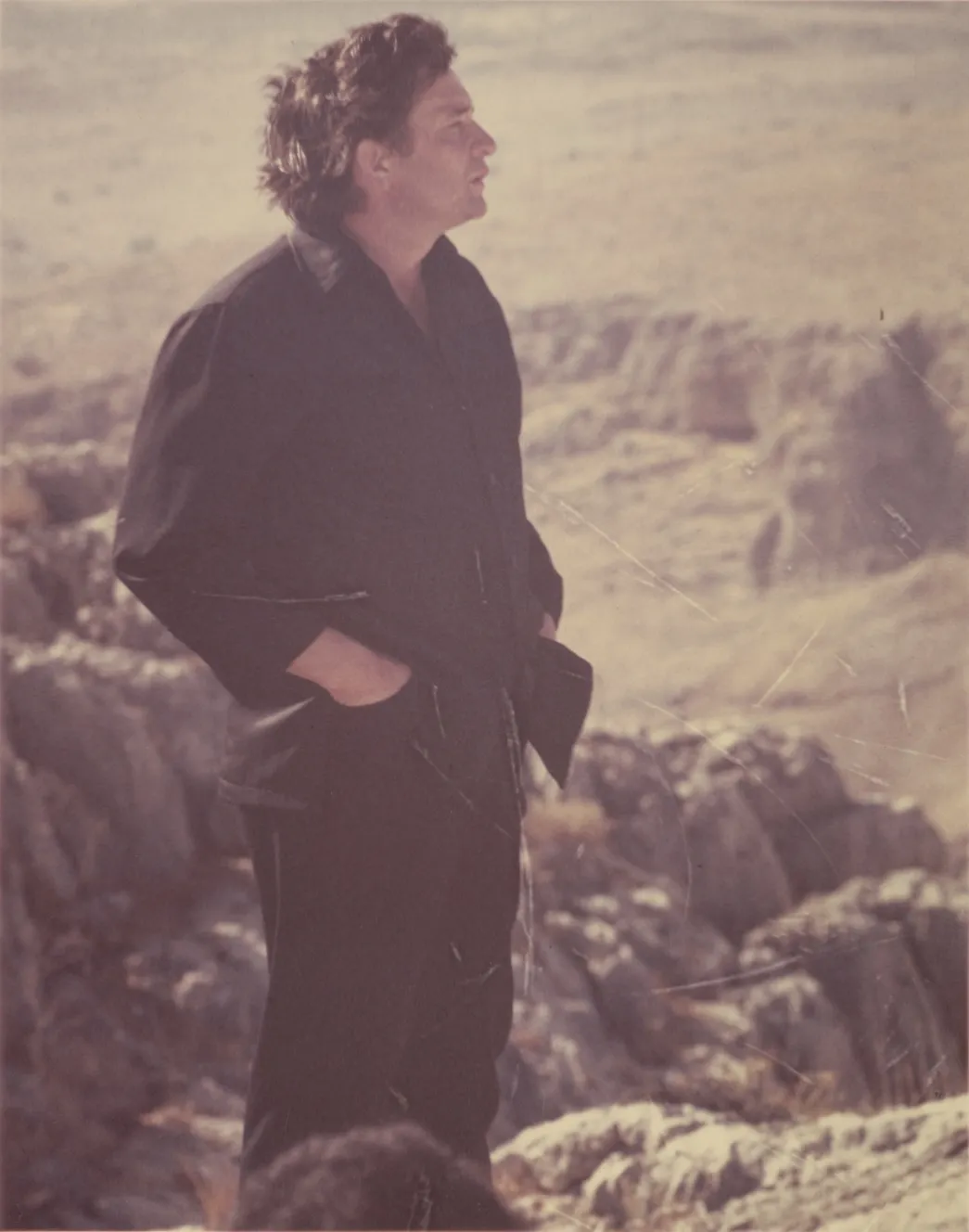

Cash attempted to summarize all of his philosophies in one of his most self-defining and self-mythologizing songs, 1971’s “Man in Black.” Here, he turns his fashion choices into a metaphor for his worldview. Though he has often explained that he wore black clothes onstage out of superstition, or for their simplicity, or because they could go longer without washing and still look clean, now the color took on symbolic meaning as a protest against poverty, war, prisons, ageism—all “the ones who are held back.”

The song solidified his standing as a beacon of social justice, an outlaw with a conscience, a rock and roll Robin Hood who would inspire future generations even if they had only passing knowledge of his music. Rosanne Cash also believed that the song offered something more personal about her father, beyond just securing Cash’s reputation as a spokesman for the ignored and oppressed.

“There’s so many levels to it,” she told Mojo magazine in 2008. “One is saying, ‘I’m wearing this symbol for the downtrodden and the poor.’ The other was much more subtle to me: it reflected the sadness, the convulsions, just that mythic dark night of the soul that he went through so many times.”

Because ultimately, what Johnny Cash and his commitment to these various causes comes down to is a concept that has become so prominent in recent years—it’s the idea of empathy. His truest concern, in his songs and in his life, often revolved around the sense of understanding someone else’s condition, trying to feel their plight. Though he survived so much that he was able to identify with those who were struggling, the truth is that his hope for connection predates his own battles with addiction or fidelity or loss. He was the Man in Black long before he identified himself as such.

Johnny Cash: The Life and Legacy of the Man in Black is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Johnny Cash: The Life and Legacy of the Man in Black © 2018 by Smithsonian Institution

Images © 2018 John R. Cash Revocable Trust