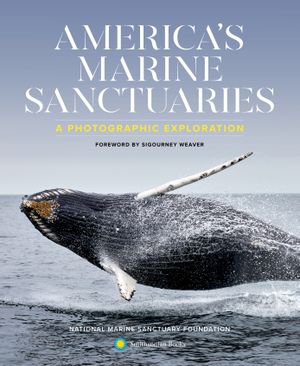

Protecting Our Ocean Planet With the National Marine Sanctuary System

Summer may be over, but you can dive into mesmerizing waters with this excerpt from “America’s Marine Sanctuaries”

:focal(375x250:376x251)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/35/c435dc2b-057c-4c3d-accb-a3374ad1b43d/pink_and_green_reefs.jpg)

The ocean is awsirl with movement. The seas that cover more than 70 percent of our blue planet are never still—they spiral around the world’s ocean basins in five great gyres created by Earth’s rotation. Every day, the gravitational force of the moon pulls the ocean back and forth across the globe. On a winter’s morning, a storm off the coast of Indonesia can churn up giant swells that roll east, traveling halfway around the world to curl into perfect tubes and break on a California beach. On calm summer afternoons, saltwater flows through the spurs and grooves of a Florida coral reef, marking the reef crest with the faintest smear of foam.

The ocean—where 99 percent of all livable space on Earth exists—is a wondrous world full of activity. The reef hums with sounds: the clackety-clack of snapping shrimp, soldierfishes’ drumlike thumps, the grinding of parrotfishes’ powerful jaws as they feed on old, stony corals. On the seabed, spiny lobsters shimmy back and forth. To the surface, microscopic marine plankton whirl. Most forms of ocean life are in motion, at least for part of their lives, looking for food, mates, or safe havens. Sea urchins move in herds through the kelp forests of the Pacific Coast, grazing on dense stands of macro-algae. Sea otters forage in these kelp beds, helping to maintain the balance of nature in these complex underwater ecosystems. Great white sharks glide along the Atlantic seaboard, wintering off Florida and summering between Massachusetts and Nova Scotia. Young bluefin tuna born in the Sea of Japan travel more than 5,000 miles to California’s coast to feed and grow to adulthood among abundant natural fish nurseries before traveling back to their birthplace to spawn.

Scattered across US waters, from the South Pacific to the North Atlantic, are more than a dozen special places known as national marine sanctuaries. Sanctuaries, like our national parks, are refuge and home to an immense array of wildlife and habitats. They preserve maritime and cultural resources that tell the history of our nation’s past. In sanctuaries, natural forces, geographic features, seasonal patterns, plants and animals, historical artifacts, cultural practices, and human uses come together to create an ecosystem of extraordinary complexity.

Since the creation of the first national marine sanctuary in 1975, the United States has protected these special places for their natural beauty, ecological importance, and cultural significance, while still allowing people to use and enjoy them. The waters of the National Marine Sanctuary System encompass living organisms, the ocean and its currents, and the seafloor itself—which may be as flat as a prairie, carved into ravines deeper than the Grand Canyon, or pierced by mountain peaks taller than Mount Everest. Sanctuary waters provide protected habitat for marine species at risk of extinction and preserve historic shipwrecks and sacred cultural sites. They serve as outdoor classrooms for school and university students and living laboratories for marine scientists. They support important industries, including recreation, fishing and shellfishing, and tourism. They are places where people come to spend time with families and friends and to fish, swim, dive, photograph, wade, explore, and enjoy the wonder of the natural world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/23/c1/23c1921e-a410-4abe-a64c-26f5907e9d18/seal_and_turtle.jpg)

The United States is a maritime nation. It has one of the longest coastlines on the planet, at more than 95,000 miles. Its exclusive economic zone—the 200-mile-wide swath of ocean waters where each nation has special rights guaranteed by international law—is the second largest in the world. Throughout our nation’s existence, the ocean has been essential for subsistence, commerce, and security.

The first legally reserved aquatic preserves were created by North American settlers in the coastal waters of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The 1641 Body of Liberties, the first legal code established in New England, affirmed that every white male householder had the right to “free fishing and fowling in any great ponds and Bayes, Coves and Rivers, so farre as the sea ebbes and flowes within the presincts of the towne where they dwell.” While early laws established rights to use and exploit the ocean, protecting marine areas in the United States for wildlife followed much later and often in response to overexploitation of a resource. One of the earliest marine conservation preserves created was in Alaska in 1869. Because the region’s booming fur trade decimated seal populations, the federal government placed two of Alaska’s Pribilof Islands and their surrounding waters off limits to all but Unangan subsistence hunters.

Until the early 20th century, underwater parks were essentially seaward extensions of protected areas on land, including state parks, national wildlife refuges, and national parks and monuments. Then in 1929, California established the San Diego Marine Life Refuge, offshore from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Two years later, early conservationist Julia B. Platt helped establish Hopkins Marine Life Refuge in Pacific Grove, California, seaward of Stanford University’s marine research station on Monterey Bay. Platt was a neurobiologist who turned to civic activism after she could not find a suitable job in academia. She became the first mayor of Pacific Grove, and a promontory in the refuge is named in her honor. These two California marine refuges may be the earliest undersea reserves in the United States not created as afterthoughts to an adjacent park on land. Decades later, in 1959, Florida’s John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park was created specifically to protect the fragile coral reefs off Key Largo, Florida.

In 1968, a single photograph gave humankind an entirely new perspective on the delicate, ocean-ringed orb that is our shared home. On December 22 of that year, Apollo 8 circumnavigated the moon. For the first time, the astronauts captured a view of brightly colored Earth rising from the blackness of space at the dawn of a new day. The perspective was startling. From space, the world appears not mainly green but a brilliant, living blue. This is our ocean planet. The picture, considered one of the greatest environmental photographs ever taken, showed how fragile our planet is, and spurred people across the globe into action to protect it. “Standing on the moon looking back at Earth— this lovely place you just came from—you see all the colors, and you know what they represent,” astronaut Buzz Aldrin said of a later Apollo mission. “Having left the water planet, with all that water brings to the Earth in terms of color and abundant life, the absence of water and atmosphere on the desolate surface of the moon gives rise to a stark contrast.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/da/91daa62c-659d-44e9-93c4-8207b7ec74d7/earthrise.jpg)

The 1960s brought a wave of support for executive and legislative action to protect the ocean. In 1966, a science advisory committee to President Lyndon B. Johnson recommended the creation of a national marine wilderness preserve system. That same year, Congress enacted the Marine Resources and Engineering Development Act. The act focused attention on the nation’s coasts and ocean and created the Federal Commission on Marine Science, Engineering, and Resources. The commission released its 126 recommendations on January 9, 1969; the report highlighted the importance of the ocean as a new American frontier for exploration, and the need to protect the nation’s ocean and coasts from pollution and overexploitation. It called for an overhaul of federal ocean and coastal programs, including the creation of an overarching National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) with responsibilities similar to NASA’s role in space, and the enactment of laws to protect the ocean and its resources.

Just days later, an environmental catastrophe revealed the vulnerability of the nation’s ocean and coasts. Beginning on January 28, 1969, and continuing for ten days, a blowout on an oil drilling platform six miles off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, spilled an estimated 3 million gallons of crude oil into the ocean. The spill shut down commercial fishing, fouled beaches, and killed countless dolphins, sea lions, seals, and more than 3,600 seabirds. At the time, the disaster was the largest oil spill in US history. Americans witnessed the oil-coated animals’ suffering far too close for comfort, through live television coverage. The public reacted with a new intensity of environmental concern and activism. The event marked a turning point in the nation’s conservation history. The activism ignited by the spill helped spur the first Earth Day, celebrated by 20 million Americans across the country, and built bipartisan support for legislation to protect the ocean.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4b/9f/4b9fa5db-7eab-4c37-bec2-036c6ccec66c/jellyfish_in_grays_reef.jpg)

In 1972 and 1973, Congress passed a series of landmark conservation laws and created the framework that has guided US ocean science and policy for the past 50 years. Among these bedrock environmental laws were the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Coastal Zone Management Act, the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act. One century after establishing Yellowstone as the first national park, and eight years after President Johnson’s Science Advisory Committee recommendation, Congress acknowledged the need for marine protected areas to conserve our ocean, and established the National Marine Sanctuary Program.

Today the United States has more than 1,000 marine protected areas of all sorts, from national marine sanctuaries to local areas set aside for conservation or research. Together they cover 1.2 million square miles, or 26 percent of the nation’s waters. They range in size from South 239th Street Park Conservation Area—a sliver of tidelands and seawater off a street-end beach access park in Des Moines, Washington—to Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, which is more than twice the size of Texas. Private entities and communities, states and territories, tribes, and the federal government, often working in partnership, manage these protected areas.

Marine protected areas provide long-term safeguarding for valued habitats, species, and features in our oceans, coasts, estuaries, and Great Lakes. Familiar examples in US waters include national marine sanctuaries, national parks, national wildlife refuges, and their state, local, and tribal equivalents. Some marine protected areas , called reserves, are “no-take” areas, where nothing can be harvested, and all the marine life is protected. Marine reserves are rare in the United States, with just over 3 percent of US waters in these no-take areas.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a4/02/a4020d36-82bd-4188-a889-cdc67d69717b/nudibranch_and_snail.jpg)

National marine sanctuaries and monuments protect marine wildlife and the habitats they call home. These treasured places are our essential network of protected waters. They connect us to our communities, our country, and our world. Each sanctuary protects habitats and maritime resources unlike any other on Earth. They are places where the public, communities, and businesses can engage in efforts to conserve our ocean and Great Lakes, for the good of the world and everything in it.

America's Marine Sanctuaries is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from America's Marine Sanctuaries: A Photographic Exploration © 2020 by National Marine Sanctuary Foundation