Honoring the Long History of Native American Service

In honor of Veterans Day and Native American Heritage Month, learn about the legacy of Native American service and the memorial that pays tribute to them.

:focal(767x577:768x578)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/90/42/9042b568-ff80-41e1-b670-27fd54b34d06/veterns_-_jesse_t_hummingbird.jpg)

“This memorial is saying: ‘We are still here. We are still viable. We still count,’” says Debra Kay Mooney (Choctaw), who served on the memorial’s Advisory Committee.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/eb/b1/ebb1edd4-17e2-4156-b714-600a844e37b7/native_veterans_memorial.jpg)

Alan Karchmer

In 1994, in recognition of Native Americans’ “long, proud and distinguished tradition of service in the Armed Forces of the United States,” the United States Congress passed the Native American Veterans’ Memorial Establishment Act. The legislation authorized the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) to create a memorial that would give “all Americans the opportunity to learn of the proud and courageous tradition of service of Native Americans in the Armed Forces of the United States.”

This law—passed a decade before the museum opened on the National Mall in 2004—was amended in 2013, allowing for placement of the memorial on the grounds of the museum and enabling the project to begin. But that was just the first step. The museum knew this monument must be built with input from those it would honor.

Work on the National Native American Veterans Memorial began with the formation of an Advisory Committee of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian veterans, tribal leaders, and families of veterans. The committee was cochaired by former Senator and Northern Cheyenne tribal member Ben Nighthorse Campbell and Chickasaw Nation Lt. Governor Emeritus Jefferson Keel, both distinguished veterans. The group grew to nearly thirty men and women who were from Native communities across the United States and represent all branches and several eras of service, from the Korean War to the present.

From 2015 to 2017, museum staff and members of the Advisory Committee spent about eighteen months consulting with Native American veterans, active duty service members, tribal leaders, veterans’ families, and community members. During thirty-five consultations in sixteen states and the District of Columbia, staff met with about 1,200 people to share plans for the memorial and gather their recommendations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f3/75/f375ff0f-3579-42f6-b2a8-654665c9cac7/quilt.jpg)

Veterans also discussed their reasons for serving in the military, foremost among these being an inherited sense of responsibility to protect their homeland, family, community, and way of life. “Why are we willing to sacrifice our lives for this country?” Rod Grove (Southern Ute) posed. “Because our great-great-grandparents’ bones are in this land.”

These consultations with community members were essential to understanding what Native American veterans and their families wish to see in the memorial, the values it must embody, and what the experience of visiting it should be. Several themes emerged that formed the basis of the memorial’s design guidelines.First, the memorial would need to be inclusive, honoring all American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian veterans, both men and women, from all branches and all eras of service. It should also respect the long tradition of service and the inherited responsibility to protect. “The memorial must reflect life,” said Yup’ik veteran Nelson N. Angapak Sr. “We were taught to love life, even to the point of risking our lives to save the life of another person.”

The memorial would also acknowledge the sacrifices made by the families of those who serve. As Commander Howard Richards of the Southern Ute Veterans Association said, “This memorial will represent all Native people, Native soldiers—men and women. [But] let’s not forget the role that the families—mainly the women, the grandmas—played in this great history of ours.”

Finally, it should reflect Native spirituality. Visiting the memorial should be a contemplative and healing experience— for veterans, families, and service members returning home. As Advisory Committee member Kevin P. Brown (Mohegan Tribe) said, “This is about the warrior, not the war.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4a/b5/4ab591cd-256e-40bd-b07c-5a90960a1666/battle_dress.jpg)

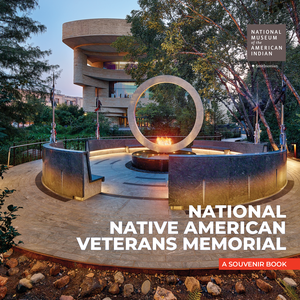

Pratt has expressed his desire to create a space that people will enter into rather than a statue or sculpture at which they can gaze. He says, “I want this to become a special, sacred place for people to come, a place for them to be healed.” The water pulsing across the surface of the drum is echoed by concentric rings in the stone of the walkways, suggesting the beat of a drum calling people to the circle.

Designed to honor Native American veterans, the memorial is also intended to educate non-Native visitors about their sacrifices. Pratt says this is part of its purpose, to welcome people “to come there and be respectful of our ways,” adding, “Maybe this will help people see Native people and realize we’re still here and very proud of this land.” He also hopes this will give visitors a place to come to remember the veterans they have lost.

Recognize and honor the military service of Native Americans this Veterans Day at the Smithsonian''s National Museum of the American Indian with a presentation about the National Native American Veterans Memorial by the memorial designer, Harvey Pratt (Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma), and curator Rebecca Trautmann; special hospitality for veterans; and a wreath-laying ceremony at the memorial, preceded by the presentation of colors by the Kiowa Black Leggings Warrior Society.

Discover more about Native American military tradition and the memorial with National Native American Veterans Memorial: A Souvenir Book, available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from National Native American Veterans Memorial: A Souvenir Book © 2022 by Smithsonian Institution