What It Took to Broker a Treaty Between the Young United States and Native Nations

Learn about the role of treaties in the relationship between early American settlers and Indigenous communities

:focal(500x386:501x387)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/45/00/4500648c-d37a-407d-bd65-849e66f11029/american_horse.jpg)

The carefully worded speech in August 1775, which had been prepared months in advance, contained metaphorical phrases that had been a part of treaty making with Native Nations for several generations. The Tree of Peace, with its long branches sheltering those who seek peace, was an ancient symbol of the Six Nations. The Haudenosaunee perceived a treaty as the mutual planting of this tree, the burying of war weapons underneath it, and the provision of goods and services to treaty allies.

It sounds like a simple matter to make a peace treaty. Say the right words, give the right wampum belts, placate the chiefs, bestow gifts upon them, and walk away with a peace treaty. No treaty, however, was that simple. A treaty is not solely words of agreement on parchment but rather an ongoing relationship in which both parties continue to have their concerns openly discussed and considered. The excerpt from the commissioners’ speech also informs us about how the colonial governments expressed respect for the intellects and cultures of the Native leaders they courted:

As proof of their sincerity, the commissioners, like the British before them, picked up on an older tribal tradition of giving wampum— long belts made of marine shell— during treaty negotiations. By using wampum belts, including a Union Belt and what they called the Large Belt of Intelligence and Declaration, the Americans showed respect for Native protocol and sought to arrive at one mind with Native leaders on important matters. Herein lies the birth of American treaty making.Brothers! We live upon the same ground with you. The same island is our common birth-place. We desire to sit down under the same tree of peace with you: let us water its roots and cherish its growth, till the large leaves and nourishing branches shall extend to the setting sun, and reach the skies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/1e/7b1e840f-66c1-4ffb-893e-128aca45c455/ancient_peace_and_friendship_belt.jpg)

At the 1775 council the commissioners explained the meaning of the Union Belt:

One of the cultural metaphors at the center of early American treaty making was the Covenant Chain of Peace. The concept behind this metaphor is of an unbreakable chain that unites treaty partners. The chain is made of three links—representing respect, trust, and friendship—that create a wide path of peace uniting the treaty partners and allowing for open, honest communication. Symbolically, the leaders of each treaty nation hold the Covenant Chain.By this belt, we, the Twelve United Colonies, renew the old covenant chain by which our forefathers, in their great wisdom, thought proper to bind us and you, our brothers of the Six Nations, together, when they first landed at this place; and if any of the links of this great chain should have received any rust, we now brighten it, and make it shine like silver. As God has put it into our hearts to love the Six Nations and their allies, we now make the chain of friendship so strong, that nothing but an evil spirit can or will attempt to break it. But we hope, through the favor and mercy of the Great Spirit, that it will remain strong and bright while the sun shines and the water runs.

To firmly hold the chain means that treaty nations do not let minor difficulties interfere with the larger peace. In fact, when such difficulties are overcome, the culture of the Covenant Chain requires that the chain be strengthened by “polishing” it with pledges to reaffirm or restore peace and friendship, provide just compensation for any harm that may have been inflicted, and keep citizens in line to avoid future infractions. The chain is the mechanism by which the treaty is made real.

For the Six Nations and many other northeastern Native Nations, the linking of arms by making a treaty was a way to bring peace and prosperity to all parties. The Mohawk name for the Covenant Chain of Peace is tehontatenentsonterontahkhwa, or “the thing by which they link their arms.” In the Onondaga language, the term dehudadnetsháus means “they link arms.” In the Cayuga language, tehonane:tosho:t means “they have joined hands/arms.”

The conceptual premise of Haudenosaunee treaty-making protocols is that mutual respect will allow trust to develop, and that such trustworthiness will result in ongoing friendship between treaty partners. The trust is symbolized in wampum belts and treaty council rhetoric as the physical interlocking of the arms, a sign of unity and strength. This linkage also will create mental, emotional, and spiritual well- being if the treaty partners are earnest in not letting human frailties destroy the treaty. This is very different than seeing treaties as only legal, political documents. It represents the Native intent of treaty making.

Two great diplomatic traditions came into play as America sought to shape its destiny as a new republic. By the late eighteenth century, both sides had become expert at negotiating treaty relationships. The roots of American treaty making can be found in Indian relations with Dutch traders and British colonists in the early seventeenth century. For the Six Nations, treaty making goes back much further, to the era of their confederacy’s formation. Their intellectual, political, and cultural treaty-making principles had been created under Kayahnerenhkowah, or the Great Law of Peace.

In the Native mind, when the American rebels defeated the British army during the Revolutionary War, the king symbolically dropped the Covenant Chain, and the Americans picked it up. Therefore, this required forging a new Covenant Chain relationship. Early American attitudes toward treaty making varied, but many American diplomats heartily embraced the custom of negotiating treaties with Native Nations. Secretary of War Henry Knox wrote to the newly elected president of the United States on May 23, 1789, reminding him of the treaty-making traditions that the Americans had inherited: “That the practice of the late English colonies and government, in purchasing the Indian claims, has firmly established the habit in this respect, so that it cannot be violated but with difficulty, and [at] an expense greatly exceeding the value of the object.” In many ways Indian protocols had become an American inheritance from the English.For northeastern Native Nations, wampum strings and belts were the main diplomatic tools for negotiating and recording treaties. Wampum are small, cylindrical beads made of shell; the beads are woven in contrasting designs of purple and white. Invitations, messages, and commitments were recorded in wampum strings. Major treaty issues and the confirmation of the agreements were recorded in woven “belts,” long bands of beads that were not worn but rather held upright when their message was recited.

Wampum was so critical to a successful treaty that American officials at times put out treaty councils until a proper number (fifty- to a hundred-thousand) of wampum beads could be acquired and woven into proper belts. An old treaty agreement could be remembered by displaying the wampum belt that was associated with it. The historical record refers to hundreds of different wampum belts, but it difficult to associate a particular belt with a specific treaty unless the written and oral history of it has been kept clear. At the same time, written notes and paper treaties do not always reflect the memories attached to wampum belts.

Perhaps the most important person at a treaty council was the interpreter who translated the Native and European languages so that the treaty partners could understand one another. Interpreters often had conflicting loyalties. Being raised within a Native society creates cultural bonds that at times clash with loyalties to outsiders. The Native delegates had to trust the interpreter and believe that that he would translate faithfully. This could be a difficult task, as some concepts in English are hard to translate well. A corrupt translator could change the meaning of words to hide the real intent of the written documents. Unfortunately, political intrigue, spying, and double talk also were traditions of treaty making. When the Haudenosaunee became suspicious of mistranslations, they asked the Society of Friends (Quakers) to witness the treaty negotiations and affirm the truth of what was being said. Quaker records show that they took their role seriously.

Experience shows us that no matter how long the history of wampum and treaty making, a treaty relationship has to be regularly renewed so that the rust on the chain does not break the spirit of the relationship. We have learned that treaties have withstood great stress, even war, but rational people will always gravitate toward peace. Treaties can be the springboard to that peace.

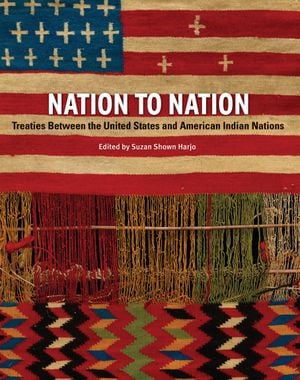

Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Nation to Nation © 2014 by Smithsonian Institution