How Bessie Coleman Pleased the Crowds and Alienated the Critics

The daredevil aviator faces mixed public opinion in this excerpt from “Queen Bess”

:focal(800x484:801x485)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/e5/71e55f37-5e2a-40fc-b898-79f9c4aac2b0/si-92-13721.jpg)

Late in September of 1922 a triumphant Bessie Coleman, only three months shy of 31, came home to Chicago. In seven years she had engineered a personal transformation from penniless Southern immigrant to South Side celebrity. The former manicurist who as a young woman had observed and admired the prominent of her community along the Stroll was now herself one of the observed and admired.

For the first time her name appeared in the social notices of the Defender when a Sunday luncheon in her honor was given by a Miss Anthea Robinson of Forty-fifth Place and attended by a married couple and four bachelors. That same afternoon, September 30, as if to remind her of the fragile and ephemeral basis of her newly established reputation, a plane crashed in the middle of Main Street in Mount Vernon, Ohio, killing both its occupants.

"Queen Bess, Daredevil Aviatrix" was undeterred by the almost daily reports of fatal accidents in the high-risk occupation she had chosen. Two weeks after she came home she gave her first air show in Chicago, the one that had been originally set for Labor Day but which publisher Robert Abbott had to reschedule when rain delayed Bessie's first New York appearance.

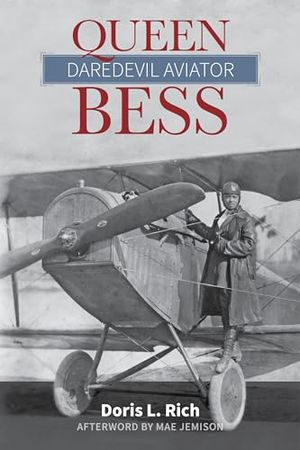

Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator

Author Doris L. Rich painstakingly pieced together her experiences using contemporary African American newspapers and interviews with Bessie Coleman’s friends and family to offer a remarkable tribute to an overlooked figure of American history.

Her flight will be patterned after American, French, Spanish and German methods. The French Nungesser start will be made. The climb will be after the Spanish form of Berta Costa and the turn that of McMullen in the American Curtiss. She will straighten out in the manner of Eddie Rickenbacker and execute glides after the style of the German Richtofen. Landings of the Ralph C. Diggins type will be made.

The Defender's "Berta Costa" was Bertrand B. Acosta, an American, not Spanish test pilot who would be one of Adm. Richard Byrd's crew to fly the Atlantic in 1927. The other Americans were Curtis McMullen, Ralph C. Diggins, and Edward Vernon Rickenbacker, all American aces of World War I. Charles Eugene J. M. Nungesser was a French ace and Baron Manfred von Richtofen was Germany's famous "Red Baron."

The same reporter wrote that on a second flight Bessie would cut a figure eight in honor of the Eighth Illinois Infantry and afterwards, presumably with Bessie at the controls, Jack Cope, veteran balloonist, wing-walker, and rope-ladder expert, would perform. On the fourth and last flight, Bessie's sister Georgia, younger by six years, was to do a "drop of death" as the parachutist. "No one has ever attempted this leap," the Defender trumpeted.

As far as Georgia was concerned it would be best if no one ever did. Certainly she would not. The night that Bessie came home with the costume she planned for Georgia to wear and blithely began to give her instructions on how to jump, Georgia shouted, "I will not, absolutely not, jump!"

"You'll do what I tell you!" Bessie shouted back.

"Who in the hell do you think you're talking to?" Georgia snapped.

They stood, toe to toe, glaring at each other until Georgia grinned and began chanting "Unh, unh, not me!" It was a chant the Coleman youngsters had used time and time again whenever Susan [their mother] wanted them to do some distasteful chore. Bessie laughed, surrendered, and arranged for Cope to do the jump.

On October 7 and again a week later, the Defender ran a two-column advertisement stating that "The Race's only aviatrix" would make her initial flight at Checkerboard Airdrome on Sunday, October 15. The admission was one dollar for adults and twenty-five cents for children.

The Defender gave Bessie the publicity but the field and plane were provided by David L. Behncke, a white man. Behncke was a rare combination of shrewd businessman and aviation enthusiast who pushed his planes to maximum performance and encouraged other pilots to do the same. An Army Air Service instructor at 19, he was five years Bessie's junior but nevertheless owned Checkerboard, where he operated his own air express and charter service, fueling and repair station, and a sales office for new aircraft.

Because of this young entrepreneur, Sundays in Chicago had become a time for pilots to show the public their skills in racing, stunting, wing walking, and parachuting. Behncke, who would later become a commercial airlines captain, and president of the Air Line Pilots' Association for thirty years, had no reservations about Bessie's race or gender. He himself had replaced her in the Labor Day show at Checkerboard that conflicted with her New York appearance and won a speed derby by flying fifty-five miles in forty-five minutes.

On the Sunday of Bessie's Chicago debut the spectators, black and white, numbered about 2,000. Among them were her mother Susan; sisters Georgia, Elois, and Nilus; nieces Marion, Eulah B., and Vera, and Nilus's son, eight-year-old Arthur Freeman. Arthur had always marveled at Bessie's stationery with its picture of an airplane on every sheet. Now, actually watching her perform, he was ecstatic. "'My aunt's a flier!,' I thought, 'and she's just beautiful wearing that long leather coat over her uniform and the leather helmet with aviator goggles! That's my aunt! A real live aviator!'"

Bessie performed in one of Behncke's planes with considerably more dash and daring than at her first show in New York. She finished the first act in ten minutes before taking off again to do a figure eight in honor of the Eighth Infantry, turning and twisting the aircraft as if she had lost control, then soaring up again.

Sixteen months earlier Bessie may well have thought that nothing would ever surpass the joy of her first solo flight in France. If she later changed her mind and transferred pride of place to her Curtiss Field experience, that would hardly have been surprising. Her New York debut was charged with the double-barreled thrill of being her first chance to display her skills to her own countrymen and the first American performance ever by a black woman flier. Still, nothing brought as much elation to Bessie as her show at Checkerboard. Her solo flight had been for foreigners; her New York show for mostly strangers. Only Checkerboard could embody the unique satisfaction of performing in her hometown, flaunting her skills before her own people, her own friends, her family.

After the show passengers lined up for rides in one of five two-seater planes on the field. Bessie piloted one while Behncke and his assistants flew the others. They continued giving rides until dark.

Among the passengers that day was only one woman, Elizabeth Reynolds, who was so delighted with her brief flight that she asked Bessie for lessons. Applying with Reynolds was an unnamed male friend, a manufacturer of "extracts" and proprietor of a cigar store at East Forty-third Street. "Extracts" were often the ingredients used in the manufacture of alcoholic drinks forbidden by law. Most of the illegal liquor on the South Side was locally produced. But for wealthy clients who were willing to pay more for imported spirits, bootleggers were beginning to use airplanes as a means of eluding the law. Bessie could have made enough money from only a dozen smuggling runs to finance her flying school. But if she ever had any such offers she turned them down.

Only three weeks after her triumphant homecoming show at Checkerboard Airdrome, Bessie put her entire career as an aviator in jeopardy. Through the assistance of Billboard critic-columnist J. A. Jackson, who had given her rave reviews for both her New York and Memphis air shows, she had signed a contract to star in a full-length feature film. In a long Billboard article Jackson wrote that the projected venture was to be an eight-reel movie financed by the African American Seminole Film Producing Company and was tentatively titled Shadow and Sunshine. Bessie, he said, would be supported by twelve experienced actors, including Leon Williams, "one of the few race members of the movie branch of [Actor's] Equity."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b3/fd/b3fd6d80-b00b-4d30-bb3b-81030c3310ff/nmaahc-2011_159_3_53_001.jpg)

But in another Billboard story scarcely three weeks later an angry Jackson wrote that Bessie "threw it up and quit cold." She did so after being told she would have to appear in the first scene dressed in tattered clothing and with a walking stick and a pack on her back, to portray an ignorant girl just arriving in New York. "No Uncle Tom stuff for me!" was her parting shot.

Jackson returned Bessie's blast with a caustic stab at Bessie's own humble beginnings in Waxahachie. "Miss Coleman," he wrote, "is originally from Texas and some of her southern dialect and mannerisms still cling to her." He followed this story with another in which he said the woman who would replace Bessie as the lead was an experienced actress with "unmistakable culture and social status which will be an asset to the company."

In an interview with Jackson, Peter Jones, president of the Seminole Company, said Shadow and Sunshine, originally intended to feature Miss Coleman, was delayed in production "because of the temperament of that young lady, who, after coming to New York at the expense of the company, changed her mind and abruptly left New York without notice to the director."

"Six autos filled with a cast of thirty people, two photographers and the directors waited in vain for two hours for the lady," Jackson wrote, "after which time Mr. Jones called upon her and was advised that she was too ill to accompany him to Curtis[s] Field for the few hours of outdoor stuff that was scheduled. That day she departed for Baltimore."

More than a broken film contract, one that he himself had had a hand in arranging, was behind Jackson's bitter denunciations of Bessie. In addition to his role as journalist and critic, Jackson aspired to be an impresario. At a meeting of the National Negro Business League he and Dr. J. H. Love, manager of the Colored State Fair of Raleigh (North Carolina), had founded the National Association of Colored Fairs. Both men were keenly aware of the desperate need for coordination in booking entertainers for the black state fairs that were just beginning to burgeon in popularity and they hoped their new alliance would end the existing state of booking chaos and confusion. But in that endeavor Bessie was to be of no help. Even before breaking her contract with the Seminole Company, Bessie had, in fact, managed to alienate both Love and Jackson as well as organizers of African American fairs in Virginia and North Carolina.

While still in Germany Bessie, acting on her own or through some unknown agent, communicated with officials of the Norfolk Colored Agricultural and Industrial Fair Association and agreed to appear at their Virginia fair on September 16. Bessie at the time was completely unaware of the existence of either Jackson or Love and could have had no way of knowing that her Norfolk booking had been arranged through their newly formed National Association of Colored Fairs. As early as July the black weekly Norfolk Journal and Guide enthusiastically reported, "Negotiations are underway to secure the wonderful colored aviatrix." And as late as September 8 the same newspaper featured a photograph of Bessie taken at her Curtiss Field exhibition in New York along with a statement that "Miss Coleman may appear at the Norfolk Colored Fair next week." But Bessie did not appear.

Since he had been instrumental in publicizing Bessie in Billboard and in setting up the Norfolk show, Jackson took Bessie's failure to appear as a personal affront. And now his new business partner, Love, was beginning to be concerned. For, when the Norfolk appearance was being negotiated, Bessie also assured Jackson she would play a date in Love's particular bailiwick of Raleigh, North Carolina. She promised she would send her final terms directly to Love but she never did get in touch with him. And, in the end, Bessie disappointed Love just as she did Jackson, flying instead at the twelfth annual Negro Tri-State Fair show on October 12 in Memphis, Tennessee.

Jackson now was publicly referring to Bessie as "eccentric," a common show-business euphemism for "unreliable." She had already had three managers in five months, he wrote. The first was William White, New York manager of the Chicago Defender. The second was Alderman Harris, owner of the black weekly New York News. And the third was "a white man whom she brought into the Billboard office. The lady," Jackson fumed, "seems to want to capitalize her publicity without being willing to work."

By this time Bessie had managed to offend men who already were or soon would be among the most powerful in the black entertainment world. Within a year entertainment entrepreneur and movie producer Peter Jones would be the manager of airshow fliers Edison C. McVey and Hubert Fauntleroy Julian and, in fact, owner of the airplane they used. Not only would Jackson continue his influential Billboard column until 1925, but he was also on the East Coast staff of the Chicago-based Associated Negro Press, a wire service used by most of the African American weeklies in the country. And Doctor Love continued his association with Jackson as promoters-bookers-organizers of black fairs throughout the United States.

When Bessie chose to do battle with Jackson, Love, and Jones, she was fighting on two fronts, in defense of equal rights for blacks in a white-dominated society and equal rights for black women in a male-dominated black society. Clearly her walking off the movie set was a statement of principle. Opportunist though she was about her career, she was never an opportunist about race. She had no intention of perpetuating the derogatory image most whites had of most blacks, an image that had already been confirmed by the Chicago Race Commission's report on the 1919 riots.

Bessie had refused to reinforce these white stereotype misconceptions or to further reduce the self-esteem of her own people by acting out on screen the role of an ignorant Southern black woman. As she herself had put it so bluntly when she stormed off the Shadow and Sunshine set, "No Uncle Tom stuff for me." Bessie was determined to bolster black pride. She was supported in this by a black press that seized on her image as both role model and grist for editorials promoting black equality.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/7f/bc7fe5f3-7e47-4a13-b82f-54249f0dc1aa/si-84-14782.jpg)

The Norfolk Journal and Guide chastised the New York Evening Journal for stating in a long article that Bessie was from Europe and "took to flying naturally without any teaching." Bessie, the Norfolk editorial pointed out, not only was an American but was forced to take flying lessons in France because no one would teach her in her own country. The Norfolk paper further took the Evening Journal to task for stating that "the colored race should supply many excellent flyers" because blacks have a natural physical balance superior to that of whites and that blacks "usually ride a bicycle the first time they try." This latter claim, the Norfolk paper said in angry rebuttal, is a typical "Arthur Brisbane thought which runs through the editorial columns of all the Hearst newspapers ... If we had more 'balance' along some other very important lines," the Journal and Guide concluded, "we would be hitting a greater stride in the race of races."

As to the balance Bessie sought—equal opportunity both for her race and her gender—the latter was far harder to attain. The majority of the nation's men, black or white, regarded women as the "weaker sex." Men headed households, governments, and businesses. Women were not even allowed to vote until the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920. And women who aspired to careers were often mocked and even feared by men who saw them as a threat to their hitherto unshakeable faith in male superiority. The Norfolk Journal and Guide, for example, the same paper that had so readily praised Bessie as a black, was notably less ready to praise her as a black woman. In a miscellania column titled "Stray Thoughts" it included the following:

Blivens: I see Miss Headstrong is taking aviation lessons.

Givens: That so'? Always had an idea that girl was flighty.

Bessie was ahead of her time as an aviator and as an advocate of equal rights for African American women. It would be three years before the rising tide of protest from black men was reflected by a blistering editorial in the Amsterdam News headed "Colored Women Venturing Too Far From Children, Kitchen, Clothes and Church."

The popular black weekly noted that "the biological function of the female is to bear and rear children," and said Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany had the right idea with his slogan of "Kinder, Kiiche, Kleider, Kirche.'' Calling black Washington, D. C., "a city of bachelors and old maids," the editorial focused on the fifty-five female teachers of Howard University, pointing out that whereas they had been raised in families totaling 363 children, or 6. 5 children per family, the teachers themselves had only 37 children, or 0.9 per family. Worse still, it said, only 22 of the 55 were married, of whom four had one child and four had none. That the average age of the unmarried teachers was over 32 disqualified them as "good breeders," the editorial said, denouncing as "race suicide" what was happening in the nation's capital. "Liberalization of women," the editorial concluded, "must always he kept within the boundary fixed by nature."

Like the Howard teachers Bessie had crossed that boundary. She married late and was not living with her husband. She had no children and had become a pilot at a time when black male fliers could be counted on the fingers of one hand. She had a mind of her own. She was neither apologetic nor ashamed of being a so-called threat to the race or an affront to its men.

After breaking her film contract, Bessie left New York for Baltimore, where she gave an "interesting outline of her work" at the monthly meeting of the "Link of Twelve" at Trinity A. M.E. Church. She also went to Logan Field on the outskirts of that city to look over a number of airplanes hut was reported to have found "none to her liking in which to take a spin."

Bessie's movie career was over before it began and her future as a stunt flier seemed in jeopardy as well. A good agent might have persuaded the Seminole Company's writer and director to reshape their script into a story stressing black pride and prowess, characteristics that would have had Bessie's approval. A good agent certainly could have eliminated her confusion over bookings for air shows. But none of the men Jackson named were really agents. White was a newspaperman put in charge of Bessie by Robert Abbott. Harris was a politician with a newspaper he used to promote his own interests. The unidentified white man is nowhere on record and may have been invented by Jackson.Bessie returned to Chicago with little to sustain her beyond pride and obstinacy. There she launched into a search for new backers. If show-business people on the East Coast would not give her a break, she would look elsewhere.

Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator © 1993 by Doris L. Rich

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.