You Don’t Need to Be Indoors to Enjoy a Smithsonian Museum. Try the Gardens!

Experience “living museums” in the nation’s capital

:focal(490x327:491x328)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/66/9c/669cf658-1972-44eb-8881-eb39f6777505/midnight_yuletide.jpg)

S. Dillon Ripley (1913-2001), the eighth secretary of the Smithsonian, recognized a golden opportunity in the landscapes around the museums. Remembering the museums and European pleasure gardens he had visited in his youth, he was determined to develop surroundings for the Smithsonian museums that would be as remarkable as their interiors. To turn mundane grounds into display gardens and ultimately to establish horticulture as a part of the institution's research and education efforts, Ripley created the Office of Horticulture in 1972. Its first director, James R. Buckler, was a visionary who was blessed with a can-do assistant director, Jack Monday, and a capable staff that embarked on the greening of the Smithsonian.

In preparation for America's Bicentennial in 1976, one of the Office of Horticulture's first efforts was a Victorian parterre, modeled after an example in Henderson's Picturesque Gardens and Ornamental Gardening (1884). The extravagant Victorian Garden was the popular forerunner of the parterre in the Haupt Garden. In conjunction with the parterre display, Buckler acquired Victorian furniture and other artifacts, which became the nucleus of what is now the Garden Furnishings and Horticultural Artifacts Collections.

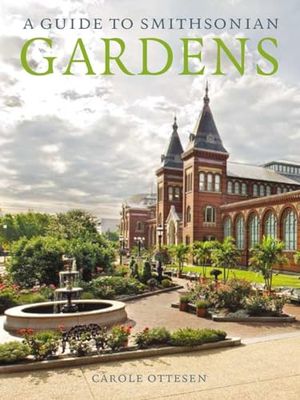

A Guide to Smithsonian Gardens

A beautifully illustrated guide to the colorful gardens that surround the Smithsonian museums along the National Mall, each unique in its design, plant materials, and purpose. Many visitors are surprised to learn that the Smithsonian Institution includes extensive gardens and landscape areas. All...

At first the Office of Horticulture was housed in a Quonset hut in the South Yard, along with a greenhouse in which employees propagated bedding materials and exotic species. As plans to renovate existing gardens and add new ones mushroomed, the available greenhouse space on the Mall was quickly rendered inadequate. Greenhouses on the historic grounds of the Armed Forces Retirement Home were leased in 1975. Soon tropical plants began to adorn the museums' interiors. Lawn areas around the museums gave way to masses of flowers, and vacant spaces sprouted gardens. The unit burgeoned into three interrelated branches, each with its own manifold responsibilities: Grounds Management Operations, Greenhouse Nursery Operations, and Horticulture Collections Management and Education.

The establishment of the Office of Horticulture coincided with a great boom in gardening in the United States that began in the 1970s. By 1986 a Gallup Poll listed gardening as the number one outdoor activity in American households, ahead of golf, jogging, boating, tennis, and swimming. Horticulture at the Smithsonian grew in tandem with the surging interest around the country.

Buoyed by the immense popularity of gardening, which spawned interest in everything from vegetables to native plants, the Smithsonian began to regard its growing roster of gardens collectively as a single botanic garden, one that is educational as well as ornamental. By 2010, when the Horticulture Services Division (successor to the Office of Horticulture) was renamed Smithsonian Gardens, its mission had also been further refined: to enrich the Smithsonian experience through exceptional gardens, horticultural exhibits, collections, and education. Not only the gardens outside, but numerous exhibitions within the walls of the museums are also informed by plants from the Smithsonian Garden’s extensive collections and collaborations between horticulturalists and curators.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/74/ef/74ef073c-d4ca-4dd3-b834-ea03d4c54c2e/hybrid_tea_rose.jpg)

As individual as the museums they enhance, the gardens of the Smithsonian are wonderfully varied. The exuberant plantings of the Mary Livingston Ripley Garden testify to the enormous range of ornamental plants available today, a happy result of the gardening boom. A stroll on a summer day through this garden, located between the Arts and Industries building and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, presents dozens of refreshing combinations of herbaceous and woody, temperate and tropical plants. The Heirloom and Victory Gardens at the National Museum of American History arise from a distinctly American past and mirror the nation's Zeitgeist at different times in its history. The Heirloom Garden is nostalgic, filled with the homey flowers cherished in simpler times. The Victory Garden commemorates the patriotic, communal spirit at home while World War II was fought half a world away.

From the more recent past, the Butterfly Habitat Garden at the National Museum of Natural History reflects a better understanding of processes in the natural world, while the terrace garden at the National Air and Space Museum is an eco-smart response to local growing conditions. The contemporary works in the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden are enhanced by complementary plantings that serve as transcendent gallery walls. The Kogod Courtyard at the Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture offers an urban retreat under an overhead canopy that is a triumph of modern technology.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6d/25/6d252c79-df66-4f7d-96b4-267713fff178/camellia_japonica_la_peppermint.jpg)

Other Smithsonian gardens are reminiscent of Old World models. The Freer Courtyard was inspired by the medieval courtyards that Charles Lang Freer visited on his travels in Britain. The Haupt Garden's parterre derives from a seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French garden style that spread throughout Europe, died out, was revived in Victorian England, and became a popular exhibit at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. The Kathrine Dulin Folger Rose Garden is a timeless classic that might as likely be found on the grounds of an ancient monastery as on the National Mall.

Some gardens break with Western gardening prototypes. The Moongate Garden at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery honors the traditions of Asia, while the Fountain Garden at the National Museum of African Art incorporates conventions from Islam's long history. The landscape surrounding the National Museum of the American Indian harkens back four hundred years to a time before there was a European presence in America and uses the region's raw materials to create a uniquely contemporary garden.

Still other gardens farther from the Mall offer respite from urban settings. The National Zoological Park in Northwest Washington, D.C., presents thousands of plants and animals in a natural environment in order to communicate the importance of nature to the welfare of both people and animals. The Arthur Ross Terrace and Garden at the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum offers access to what was once one of Manhattan's largest private gardens.

Despite the wide diversity of the Smithsonian gardens, all benefit from environmentally sensitive practices that horticulturists employ each and every day. Handsome natives grow in most of the gardens. Landscaping with native or climatically suitable plants provides an environmentally appropriate and arresting alternative to traditional landscaping. In a similar vein, Smithsonian Gardens practices integrated pest management as a way of controlling garden pests using methods that are the least hazardous to people and the environment. These are just a few of the countless elements in the Smithsonian gardens that inspire and set examples for visitors from all over the world.

Carefully planned to advance the mission and enhance the experience of the museum it surrounds, each of the Smithsonian gardens is distinctive and ever evolving. Most are situated along the Mall, a prominent feature in a plan that was executed when the city of Washington was little more than a magnificent intention. All together, these Smithsonian gardens compose a living history of gardening in America.

A Guide to Smithsonian Gardens is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from A Guide to Smithsonian Gardens by Carole Ottesen © 2011 by the Smithsonian Institution

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.