The Legacy of the Cherry Blossom Festival

Washington, D.C., has one of the world’s greatest celebrations of spring

:focal(363x290:364x291)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/41/a7/41a792f6-8811-48be-8e22-25278c1db46d/georgia_float.jpg)

When 3,020 Japanese flowering cherry trees were shipped from their native land to Washington, D.C., it would have been hard to imagine how enthusiastically they would be embraced. They came to perform much the same role in the United States capital that they had in Japan: harbingers of the new season, bringing joy and spurring celebrations every spring. Cherry blossoms have since become widely emblematic of Japan, its people, and American appreciation of Japanese culture. The annual blossoms have inspired events and traditions that salute natural beauty and the cultivation of friendship between the people of the United States and Japan.

By 1916, the cherry trees received in the 1912 gift from the city of Tokyo were thriving. In 1927, local schoolchildren reenacted the planting of the 1912 trees, which is considered to be the first Cherry Blossom Festival. In 1934, the District of Columbia’s Board of Commissioners sponsored a three-day celebration, and the festival was officially established in 1935. After several years of an informal pageant, in 1939 ,the National Conference of State Societies, a member organization based in Washington, began recruiting college-age women to serve as “cherry blossom princesses” and “represent their states in a festival parade and ceremonies.” After a suspension between 1942 and 1947, during and after World War II, the festival was relaunched in 1948 and became a remarkable annual event, reaffirming prewar ties of friendship between the United States and Japan.

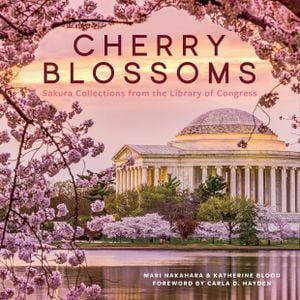

Cherry Blossoms: Sakura Collections from the Library of Congress

A beautiful gift book commemorating the nation's most cherished springtime tradition, the National Cherry Blossom Festival, through original works of art from the Library of Congress collections

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b8/a9/b8a937f8-d8db-428c-a888-a8e882a43fab/sightseers.jpg)

Presented with the ceremonial Mikimoto Pearl Crown, a 1957 gift from Japan’s iconic pearl jeweler, the new queen makes her first appearance in the National Cherry Blossom Festival Parade and travels to Japan as a young diplomat. During her visit, she meets with Japanese leaders such as the prime minister and the governor of Tokyo and also makes courtesy visits to the Ise Shrine, the Ozaki Gakudo (Yukio Ozaki) Memorial Foundation, and other important sites. More than 3,000 young women have participated in the program.

Over time, the scale of the festival has grown, and it now lasts more than three weeks. Often called the nation’s greatest springtime celebration, the current festival promotes “traditional and contemporary arts and culture, natural beauty, and community spirit.” As an official participant in the festival since 2012, the centenary of the gift, the Library of Congress has been hosting various programs—including an exhibition featuring the Library’s extensive and growing collections related to the 1912 gift, the National Cherry Blossom Festival, and the wider history of cherry trees in Japan and beyond; filmed talks; and a recurring K–12 program in collaboration with the Japan-America Society of Washington, D.C. and the National Conference of State Societies.

Hiroshi Saitō, who served as Japanese ambassador to the United States during the crucial prewar years from 1934 to 1938 and is remembered for his commitment to peace, observed during the 1936 celebration that cherry blossoms are “to be enjoyed best in clusters, each flower losing its individuality in the perfection of the whole, turning the scene into a veritable fairyland.” Saitō also recalled the memorable moment of the cherry trees' arrival in 1912, when he was just beginning his diplomatic career. Saitō’s speech, delivered almost a quarter century after the gift and as the world seemed to be on the brink of war, can be interpreted as a wish for peace: as individual blossoms unite into clusters, so flower viewing encourages people to unite in a spirit of friendship and peace.

The usual life span of ornamental cherry trees is about 30 to 40 years, and despite the National Park Service’s expert care, the original trees have been declining in number. Regardless, their legacy is a lasting one. As Saitō said, the cherry blossoms “never die, for their memory lingers long in the minds of those who have seen them, and every spring there comes with them the promise of new birth.

Cherry Blossoms: Sakura Collections from the Library of Congress is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Cherry Blossoms by Mari Nakahara and Katherine Blood © 2020 by Smithsonian Institution and Library of Congress

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.