SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

Facing History: Lessons from the Potter’s Wheel

Jim McDowell, known to many simply as “the Black Potter,” is a ceramicist who specializes in stoneware face jugs.

:focal(600x0:601x1)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/jim-mcdowell-portrait.jpg)

“I can talk to you, but I talk much better at the wheel.”

Jim McDowell turns up the speed of his potter’s wheel, as bits of slurry and clay fleck his cheeks. His hands cup the sides of the column of clay spinning at its center, bringing the height higher and higher before pressing the clay back down again to properly center things. It’s like watching the ebb and flow of the tide: measured and strong.

McDowell, known to many simply as “the Black Potter,” is a ceramicist who specializes in stoneware face jugs, a type of vessel bearing the likeness of the human face. Through his work, he honors the origin of these culturally rich vessels and reflects on “living while Black” in America in order to call out the racism and injustice endemic to this country. At seventy-five years old, McDowell says he is busier than ever.

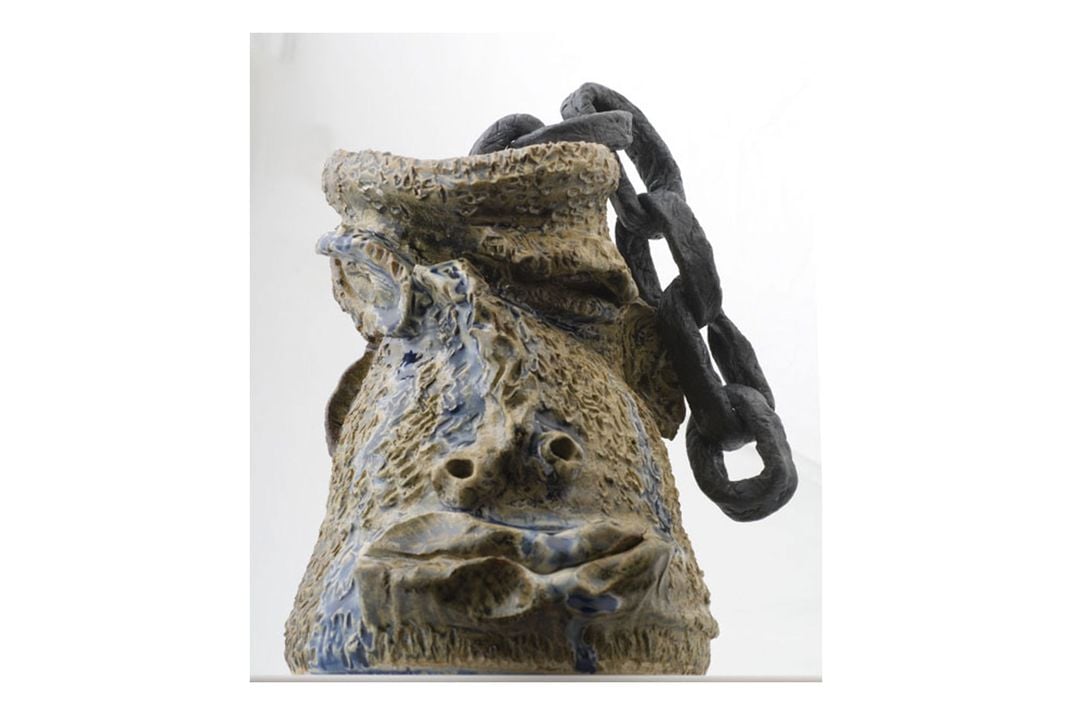

“The story I’m telling, it’s that enslaved people came here, and they survived and thrived when every hand was stacked against them,” McDowell says. “I’m speaking for those who are marginalized, for those who were brought here in chains. I’m speaking for those who were told, ‘You ain’t nothin’ but a n*****,’ and those who were never given an opportunity.”

McDowell turns off the wheel and takes us back nearly two centuries to a place just 150 miles from the North Carolina workshop where the two of us sit.

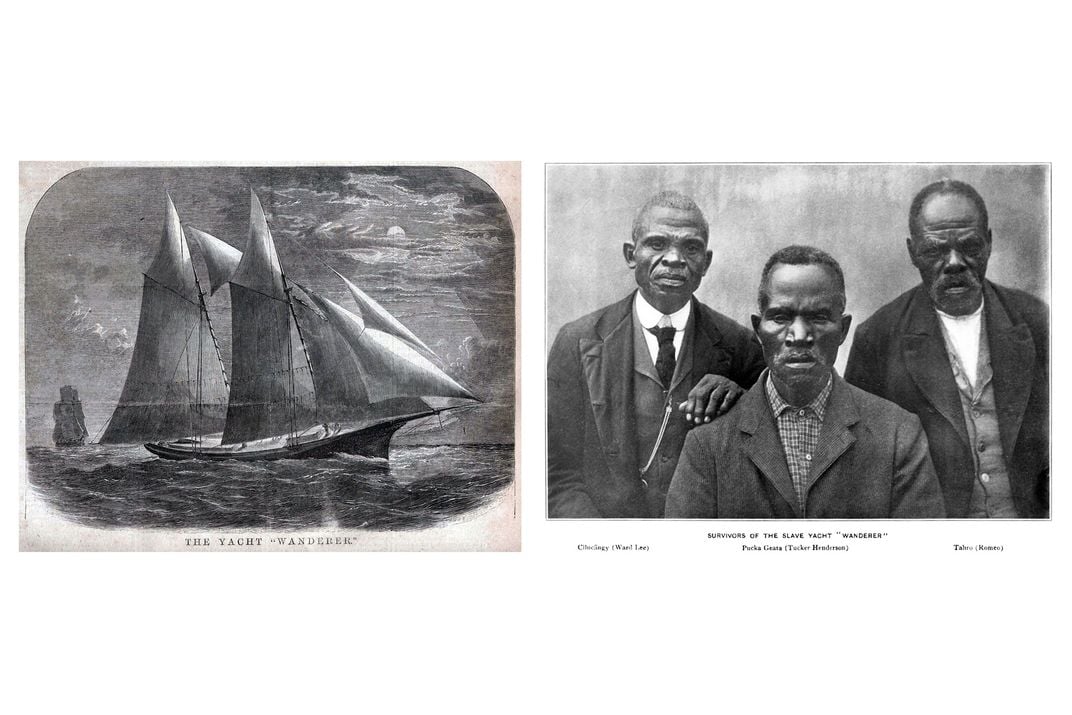

“When and where did this start?” he ponders. “The Wanderer. That seems to be the linchpin.”

In November 1858, a racing yacht reached the coast of Georgia carrying an illegal cargo of enslaved Africans. That boat was Wanderer, and most of those shackled on board were Bakongo, a Kikongo-speaking Bantu ethnic group from central and western Africa. Many of the 400 who survived the voyage were taken to Edgefield County, South Carolina, where a pottery industry thrived on a foundation of slave labor.

Potteries were owned and operated by white Southerners who, McDowell says, used those they enslaved to dig clay, mix glazes, and produce pottery for their operations. Though it’s possible that enslaved potters made face jugs in Edgefield prior to the influence of the Wanderer group, the development of the form after their arrival in 1858 is telling.

“These people were from the Kongo, and their culture was intact. Their language was intact, their customs were intact, because they didn’t break them up. Back home, they would make things to honor babies being born, or when someone died, or for protection. They honored their ancestors and practiced spirit worship.”

In the utilitarian pottery that dominated life in Edgefield, it seems the enslaved passengers of the Wanderer found a new medium in which to preserve some of those customs and beliefs. Contemporary historians, including John Michael Vlach, see direct connections between Bakongo culture and the Edgefield face jugs. Research points particularly to the concept of nkisi, where objects or figures are crafted to house spirits. These figures are imbued with power by a ritual specialist, or nganga, and serve multiple purposes: calling upon spirits for protection, punishment, or to settle disputes. Commonly, the stomachs of nkisi figures are hollowed out to hold magical or medicinal items, called bilongo. In the case of Edgefield face jugs, the use of white kaolin clay for the eyes and teeth is thought to hold great importance, as white was representative of the spirit world in many African cultures, and kaolin itself was used as bilongo in nkisi figures.

Similarly, Bakongo belief places the land of the dead beneath lakes and rivers, with water used to connect spirits to the world of the living. Though Edgefield face jugs were quite small, with most only about five inches wide by five inches tall, they were known to contain water. This small size is key in understanding that face jugs likely held water not for utilitarian purposes but for ritualistic or symbolic purposes.

In this way, McDowell sees face jugs as a representation of cultural adaptation and the merging of traditions and beliefs. He refers to this process as the “amalgamation of cultures, beliefs, and religion.” Further, the multitude of customs already present among Edgefield’s enslaved African and African American community and the restrictions of enslaved life in South Carolina brought further importance to the Bakongo-inspired vessels. McDowell cites oral stories involving face jugs placed in graveyards as an example of this amalgamated purpose.

“Since slaves were chattel, they weren’t considered people, and they weren’t allowed to have a grave marker. So sometimes they’d put a face jug on your grave. If it was broken after a period of time, that means you won the battle between the Devil and God, and your soul was set loose to heaven.”

It is important to note that anthropomorphic vessels and jugs have existed in many cultures throughout history. Examples include the English “Toby jug” and the Germanic Bellarmine jug, or “Greybeard.” A handful of face jugs are even known to have been created by Northern-trained white potters in America prior to 1858, with speculation that they were influenced by these European traditions. Many experts agree, though, that the face vessels created by Black potters in Edgefield represent a tradition distinct in form and purpose.

However, by the early twentieth century, the cultural and spiritual significance of the face jug was supplanted by appropriation. White potters began making face jugs of their own in the style of Edgefield jugs as demand for stoneware storage vessels steadily fell.

“When they started making their face jugs, the highways started coming through,” McDowell says. “It was a novelty. They could sell them to tourists. It was a moneymaker.”

Soon, there were mostly white hands forming these dark faces. They began to look increasingly different—“cartoonish,” as McDowell says—and took on new meanings. One popular story perpetuated in white communities claims that face jugs were made to look scary to keep children from trying the moonshine that might be stored inside, a purpose starkly contrasting their sacred origins. The form came to be seen as a folk tradition of the white American South, gaining widespread recognition in the 1970s through the work of artists like Lanier Meaders and Burlon Craig, and persisting to this day.

In the creation of his jugs, though, McDowell says he’s taking the art form back.

“You won’t see anything in my jugs that look like the white potters’. That’s because I’m Black. And being Black does not mean my color; it means my culture, my morals, the way I perceive things, the way I feel things. I do have a history—my lineage is back there.”

Indeed, there’s no mistaking a Jim McDowell jug. In their asymmetrical noses, deep-set eyes often accented with colorful tears, and crooked teeth, McDowell imbues his jugs with a sense of pain that sets them apart.

“My jugs are ugly because slavery was ugly,” McDowell says. “I have their DNA. It’s in my brain, it’s in my body, and it’s in my skin. It’s all over me, so I can’t get away from it… and now I have that pain and anguish.”

In his face jugs, McDowell also honors Dave Drake, an enslaved person from Edgefield who made pottery in the mid-1800s. Though Drake was not known to make face jugs, he was extremely skilled and created stoneware vessels of immense size. He also did something unprecedented for a man in his position: he signed his name to his work and wrote on his pottery, authoring beautiful poems about his own life, the qualities of his stoneware, and about slavery. In a time when literacy was illegal among the enslaved, Drake’s poetry was an act of rebellion.

McDowell sees Drake’s life and the stoneware vessels he created as a testament to the genius and perseverance of enslaved peoples in this country. But in Dave Drake, these qualities have a face, a name, and a written record. It’s a legacy that McDowell hopes to sustain in his own work.

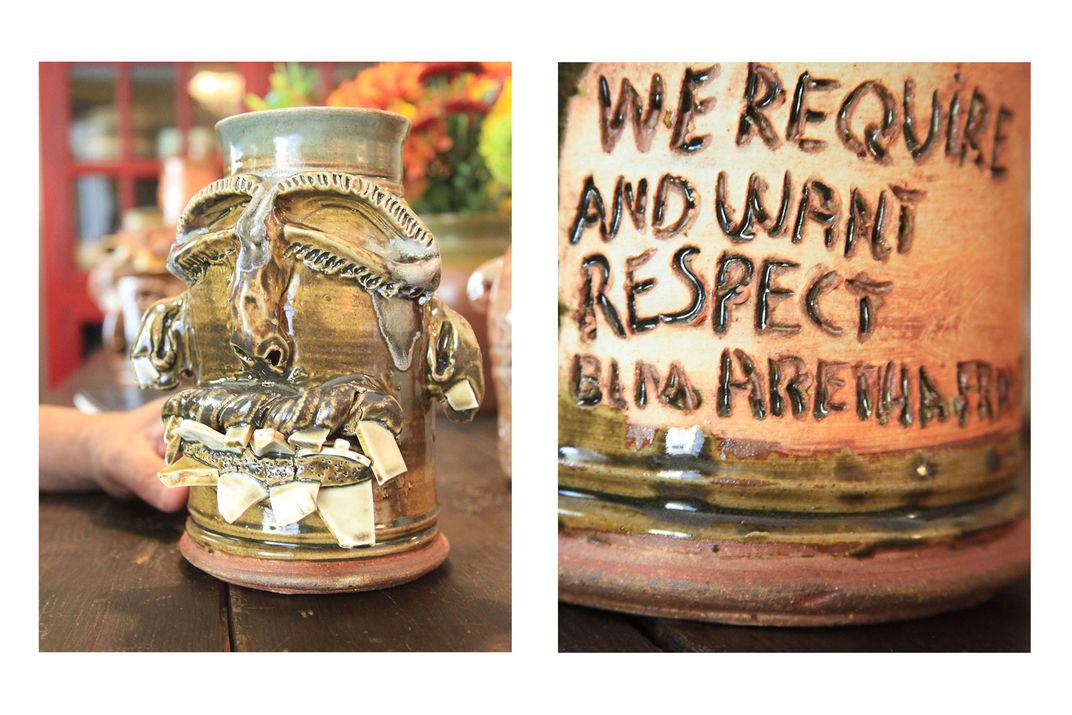

“Dave’s my inspiration. In the midst of not being able to have anything but your hands, your creativity, and your mind, Dave survived. You see the double lines on my jugs?” McDowell asks, referring to two parallel lines circling the mouths of his jugs. “That’s for Dave. That’s what he did on his pottery, and I want to honor him and remember him. I also write on my jugs like him. When I first started, the left side would be something about slavery and the right side would be something going on today.”

In his work, McDowell makes clear that his inspiration is rooted not only in the words of Drake and the Edgefield face jugs, but in how the initial work of enslaved potters would have transformed had the practice continued among Black potters.

“I’m the bridge. The tradition was interrupted, but I picked it up on this side, went with what I had, and built on it from there.”

McDowell’s work brings the face jug into the twenty-first century, filling in the gaps of more than a century’s worth of history, downplayed achievement, and injustice. He adds and augments in recognition of the things that have changed over the past few centuries—and of those that haven’t. You can see this evolution in the materials McDowell uses.

“To do this, you’ve got to learn to use everything that most people would call waste,” McDowell says. This sort of ingenuity, he tells me, allowed enslaved potters to make their original face jugs, so he continues working in this mindset, even with modern materials. For his clay, he still collects the scraps of past projects, called “slop,” to stretch his supply farther. He buys broken china at thrift stores to repurpose for the teeth of his jugs, replacing the white kaolin clay. Kaolin is also missing from the eyes of McDowell’s face jugs—a choice, he says, that stems from a modern association with these stark white features: “I don’t do that. I’ve moved on and I don’t want my jugs to have that. That’s like blackface to me.”

Instead, McDowell shapes his eyes from coils of clay, placing broken glass in the eye sockets that liquefies into tears under the heat of the kiln. Occasionally, he adds features to his jugs like wings to honor those who have passed, or a pipe to indicate status as an elder or person of honor.

Beyond updating the composition of face jugs, bridging the tradition requires a new interpretation of their purpose in modern America. In his face jugs, McDowell sees not only an opportunity to preserve history and celebrate the work of those before him, but a chance to start conversations about racism. He sees an art form that can access visceral feelings and promote social justice.

McDowell traces this aspect of his work to a jug he created nearly fifteen years ago: “The Slave.”

“‘The Slave’ was a transition point for me. I was sitting in the shop, and I had this thought in my head: what possessed the white person to beat someone for no reason? So I made a jug and took a clothes hanger, and I beat the jug. Just beat it. When I beat my own jug, I was hitting me. I became the oppressor for no reason. And it tore me apart. And after, I put a cloth over it, covered it up for a long time. I was trying to do what so many Black folks do with pain: stuff it down. It wasn’t until my wife Jan came along and told me that people needed to see it that I brought it out.”

When people did see it, McDowell finally recognized the weight of his work and its capacity to convey so much of the pain and anger he had kept hidden away.

Upon being shown at a gallery in New York with a few of his other jugs, ‘The Slave,’ with its badly beaten surface, sold almost immediately, and for more money than any jug of his ever had. Reflecting on that moment, McDowell says, “I think they felt the anguish. They felt the pain. I’d always had this thought, how can an idea become concrete? As an artist, I saw I could do that.”

*****

I follow McDowell through the halls of his home and into an open, light-filled room. At a table covered in books and bits of paper, a sea of faces waits for us. McDowell takes a seat, gesturing for me to do the same. He picks up a jug with a bright, boyish face, lips slightly parted as if frozen in a moment in time.

“This is Emmett.” He says it not as a description, but as an introduction to the boy himself: Emmett Till. Till was a fourteen-year-old African American boy murdered in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of whistling and grabbing at a white woman. His two murderers were acquitted by an all-white jury, and, six decades after the fact, his accuser recanted her allegations.

In his jug “Emmett Till,” McDowell preserves the memory of Till while reflecting on his own experience as a ten-year-old boy internalizing the murder. “It scared the hell out of me. I remember seeing his picture in Jet magazine, when he was in the casket. His mother said, ‘I want you to see my baby. I want you to see what they’ve done to him.’”

As McDowell slowly turns the jug around, Emmett’s face disappears, replaced by a combination of cuts, indentations, purples, greens, and reds—the surface beaten and tortured beyond recognition. In these two sides of “Emmett Till,” McDowell depicts the gruesome reality of a boy hated only for the color of his skin. He sets into the clay the fear and anger that’s existed in him since he saw that photo in Jet: the fear that anyone who looked like him could be next, and the anger that such injustices continue more than sixty years after Till’s body was found in the Tallahatchie River.

Today, McDowell continues to shape the harshest realities of Black life into his work. For Trayvon Martin, an African American teenager murdered in Florida by a neighborhood watch captain, he cut the front of a jug into a hoodie, using the back, inside wall of the jug to affix Martin’s face. The resulting work finds a diminutive, kind face dominated by the hood framing it—a parallel of the profiling and racism that led to his murder.

This past summer, McDowell created a jug to honor George Floyd, the African American man suffocated by a police officer kneeling on his neck. For more than eight minutes Floyd begged for his life and pleaded for his mother. McDowell’s jug, “Miss Cissy,” serves as a response to Floyd’s calls that could never be answered. On the back of a jug adorned with angel’s wings, he writes a message from Cissy: “I’m coming for you son!”

Over the past year, McDowell has begun marking every jug with “BLM,” a nod to the Black Lives Matter movement. “I write BLM on my jugs because for so long we’ve been told we’re not worthy and not capable, but the world needs to know the contribution Black people have made to this country and are still making to this country. We need to be included.”

This idea that the history, contributions, and experiences of Black Americans have been covered up or made to be invisible is crucial in McDowell’s work. Looking at a Jim McDowell jug, you’re confronted by stories that are constantly ignored and voices that need to be amplified. In the detail meticulously shaped into each face and the words etched into its reverse side, you see a person and a lived experience—not just the Black culture and labor this country has exploited for so long.

One of his most recent jugs, sitting among a group readying to enter the kiln when I saw it, gets directly at this point. The face is only half glazed, creating the effect that it’s disappearing into the clay itself.

“I made that jug to look like half the face is gone, because today some Black people are invisible. You don’t see us. You don’t know us,” McDowell says. “So, on the back of the jug I wanted to ask that question: If I disappear today, will you look for me?”

Tommy Gartman is an intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a graduate of Tufts University. He wishes to thank Jim McDowell and Jan Fisher for their hospitality and generosity throughout the course of this story.

Further Reading

Claudia Arzeno Mooney, April L. Hynes, and Mark Newell, “African-American Face Vessels: History and Ritual in 19th Century Edgefield,” Ceramics in America (2013)

John Michael Vlach, “The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts” (1990)

Mark M. Newell with Peter Lenzo, “Making Faces: Archaeological Evidence of African-American Face Jug Production,” Ceramics in America (2006)

Robert Farris Thompson, “African Influence on the Art of the United States,” African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 7, (2010)