SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

Cicada Folklore, or Why We Don’t Mind Billions of Burrowing Bugs at Once

The earliest documented examples of cicada folklore come from China.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Snodgrass_Magicicada_septendecim-1.jpg)

For at least forty million years, the cicada has epitomized reincarnation. Nesting beneath the earth—some for as long as seventeen years (in the case of certain “periodical” cicadas)—they suddenly stir as if by some inexplicable, insectual instinct. The bugs burrow to the surface, where they shed their exoskeletons, sing (if male), mate, lay eggs (if female), and then die—all within a month of their above-ground appearance. Their offspring hatch from the eggs, fall from the trees, and burrow underground, from which they will emerge the following year (if annual cicadas) or after another thirteen years or seventeen years (if periodical cicadas).

This summer, billions of these bugs will reenact this cycle in fifteen states east of the Mississippi River—from Michigan and New York to Tennessee and Georgia—plus our own Washington, D.C. The Washington Post reports that “some places will have more than a million cicadas per acre, which could equate to more than 25 or 30 per square foot.” This year’s cicadas belong to Brood X—as in Roman numeral ten, not some team of mutant superheroes. We know that the ancestors of today’s cicadas enthralled our own human ancestors, thanks to the fascinating folklore we can find.

The earliest documented examples of cicada folklore come from China, where stone carvings of the bug date to 1500 BCE. Seeing how the cicada would shed its nymphal exuviae—usually leaving the empty shell on a tree—and then begin its adult life in a new winged body, the Chinese regarded cicadas as symbols of rebirth. Accordingly, they carved cicadas out of jade, placed them on a corpse’s tongue before burial, and then imagined that those deceased individuals would similarly emerge out of their decaying bodies and achieve some sort of permanent immortality, much like the piece of jade itself. Other elements of Chinese folklore portray the cicada as pure and lofty, according to Jan Stuart, curator of Chinese art at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art: “pure because they subsist on dew and lofty because of their perch in high treetops.”

High regard for cicadas is also found among the Hopi people of northern Arizona, who may have come originally from Asia, though Hopi mythology indicates that they emerged in the Grand Canyon by way of a “fourth world,” at a time when water covered the earth.

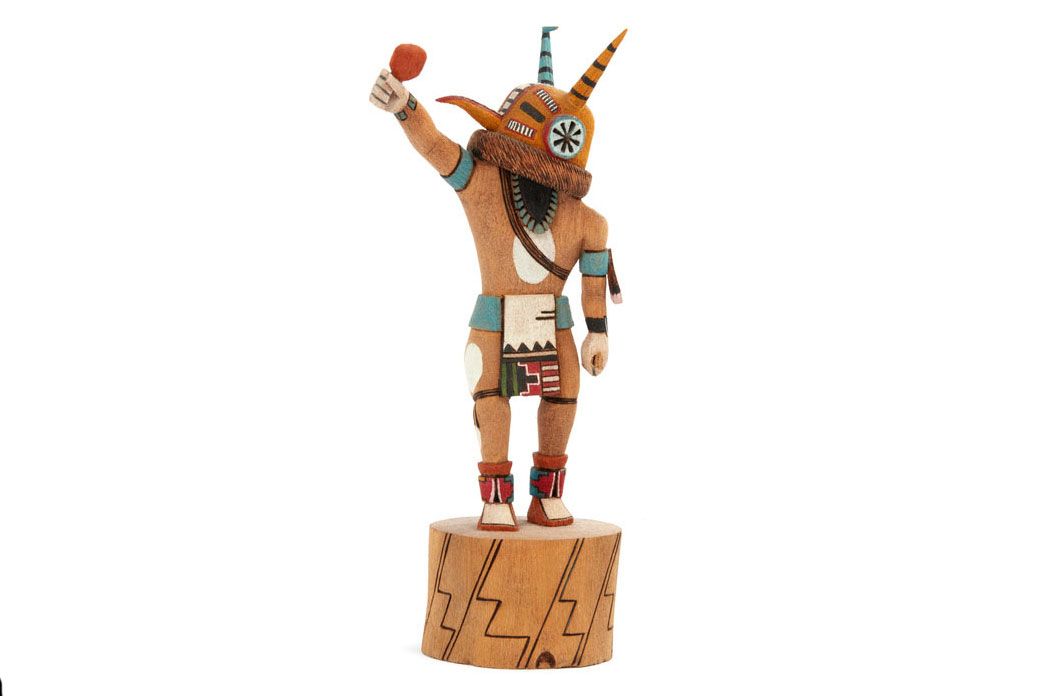

According to some sources, two cicadas (known in the Hopi language as maahu) successfully led theHopi people into the fourth world. Those two maahu played flutes—akin to the buzzing of cicadas—which miraculously healed their bodies when pierced by arrows shot by the eagles that guarded the entrance to the fourth world. Contemporary Hopi artists, such as Gerry Quotskuyva, carve traditional katsinas (or kachinas, spirit beings) of the maahu to reinforce their roles as spiritual messengers for the Hopi people.

As with the Hopi maahu, the buzzing sound may be the cicada’s most distinguishing characteristic, especially when they intend to mate. But whether we hear their buzzing as a flute-like healing, or more akin to the ninety decibels emitted by “a lawnmower, dirt bike, or tractor”—as noted by the National Institutes of Health’s Noisy Planet Campaign—may be a matter of opinion or of folklore.

To better understand those sounds, the diverse collections of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings and the Smithsonian Folklife Festival are tremendous resources—with more than a dozen cicada tracks, including seven albums (see References below). Some are recordings of actual insects, while others are musical mimicries of cicada sounds. One of the latter, recorded at the 2013 Folklife Festival, comes from the Dimen Dong Folk Chorus from China’s Guizhou Province.

Another example is “Utom kuleng helef” (Call of the cicada), featuring Lendungan Simfal and Ihan Sibanay playing bamboo zither in a village near Lake Sebu in southwestern Mindanao, Philippines, in 1995. These two women—both members of the T’boli people—play utom, which the album’s liner notes describe as “interconnected sounds, ideas, experiences, and sentiments” that suggest “sounds and images emanating from the natural world [that] are interpreted as signs from the nature spirits.” On a literal level, this particular utom “alludes to the unrelenting and shrill calling of the cicada at sunset.” However, the song’s allegorical meaning also evokes a specific myth shared among the T’boli:

The cicada, whose father is the sun and whose mother is the moon, is indolent and dependent upon others. As the sun sets, it cries for fear of losing its father who disappears over the crimson horizon. Left behind with feelings of abandonment, the cicada is anxious about his survival and attempts to end his life with an endless, longing cry.

Folklorists love to find similarities among world myths, legends, and folktales. We debate about whether it’s because those narratives began in one particular place and then spread to other cultural groups (a process we call monogenesis and diffusion) or because the narratives arose independently in several places (a process known as polygenesis, which Carl Jung’s theory of collective unconscious may support).

Whatever the explanation, the T’boli myth shares elements of the ancient Greek myth of Eos, the goddess of the dawn, known to the Romans as Aurora. Because her lover, Tithonus of Troy, was merely human, Eos asked Zeus to grant him immortality. But even goddesses sometimes don’t read the fine print, because Eos forgot to ask for his eternal youth as well. As a result, she doomed Tithonus to remain alive, but to grow so old that he sank into “toothless decrepitude and prayed then that he might die,” as described by J.G. Myers in Insect Singers: A Natural History of the Cicadas (1929). Eos understood that gods never rescind their gifts, but not knowing what else to do with Tithonus, she locked him in a room and “changed him into an ever-complaining Cicada.”

It remains to be seen whether the Brood X cicadas of 2021 will become complainers like Tithonus, or simply go about their business as they have millions of times before. But any of us in their vicinity may wish to take some time to observe their endlessly fascinating rituals. These bugs don’t bite, and if we’re in the mood we may want to take a bite out of them—fried, roasted, toasted, or even dipped in chocolate. We won’t have the same opportunity again until 2038.

References: Cicada Sounds from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

- Bosavi: Rainforest Music from Papua New Guinea (2001). Includes “Ulahi and Eyo:bo Sing with Afternoon Cicadas,” as part of an intimate musical portrait of life from the first generation of Bosavi people in an independent Papua New Guinea.

- Dream Songs and Healing Sounds in the Rainforests of Malaysia (1995). Includes “Cicada in Malaysian Rainforest,” as part of a collection of spiritual dreamsongs among the Temiar people of the central Malaysian rainforest.

- Navajo Songs (1992, from a 1933 recording). Includes the track, “Moccasin Game Song: Cicada or Locust Song,” which explains why cicadas lack nostrils.

- Sounds of a Tropical Rain Forest: Produced for the American Museum of Natural History(1952). Includes two tracks of cicadas recorded during the dry season of a tropical rainforest in eastern Peru.

- Sounds of a South African Homestead (1956). Includes sounds recorded at dawn, titled “Bush Birds: Cicadas, Oriole, Bulbul, Robin, Shrike, Cuckoo, Starling (Herder Whistling).”

- Sounds of Insects (1960). Includes “Cicada Warm-up and Flight,” “Cicada Song,” “Cicada and Plane,” and much more, recorded and annotated by entomologist Albro T. Gaul.

- Utom: Summoning the Spirit (1997). Includes three tracks of “Call of the Cicada,” from the T’boli, a group living in small, scattered villages in the mountains and valleys of southwestern Mindanao, Philippines.