SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

The Swedish Witch Trials Teach Us How to Confront Dark Heritage

At first glance, the tradition of Påskkärring, or “Easter Hags,” seems quite innocent, but deeper study reveals a dark history, one of oppression and persecution.

:focal(450x300:451x301)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/23/e3/23e3bd0a-7aad-40d6-bfe9-d4a9b619caac/witch-costume.jpg)

Photo by Victor Tornberg, courtesy of Vänersborgs Museum, Creative Commons

In Sweden, during Easter, you are not surprised to see children dressed up in ragged clothing, with dark makeup and a broom between their legs. These “witches” wander door to door, collecting candy from the neighbors, much as trick-or-treaters do for Halloween, but in exchange for small gifts, like homemade drawings or postcards. At first glance, the tradition of Påskkärring, or “Easter Hags,” seems quite innocent—these are children after all, and it’s suspected the tradition has gone on since the early 1800s. But deeper study reveals a dark history, one of oppression and persecution.

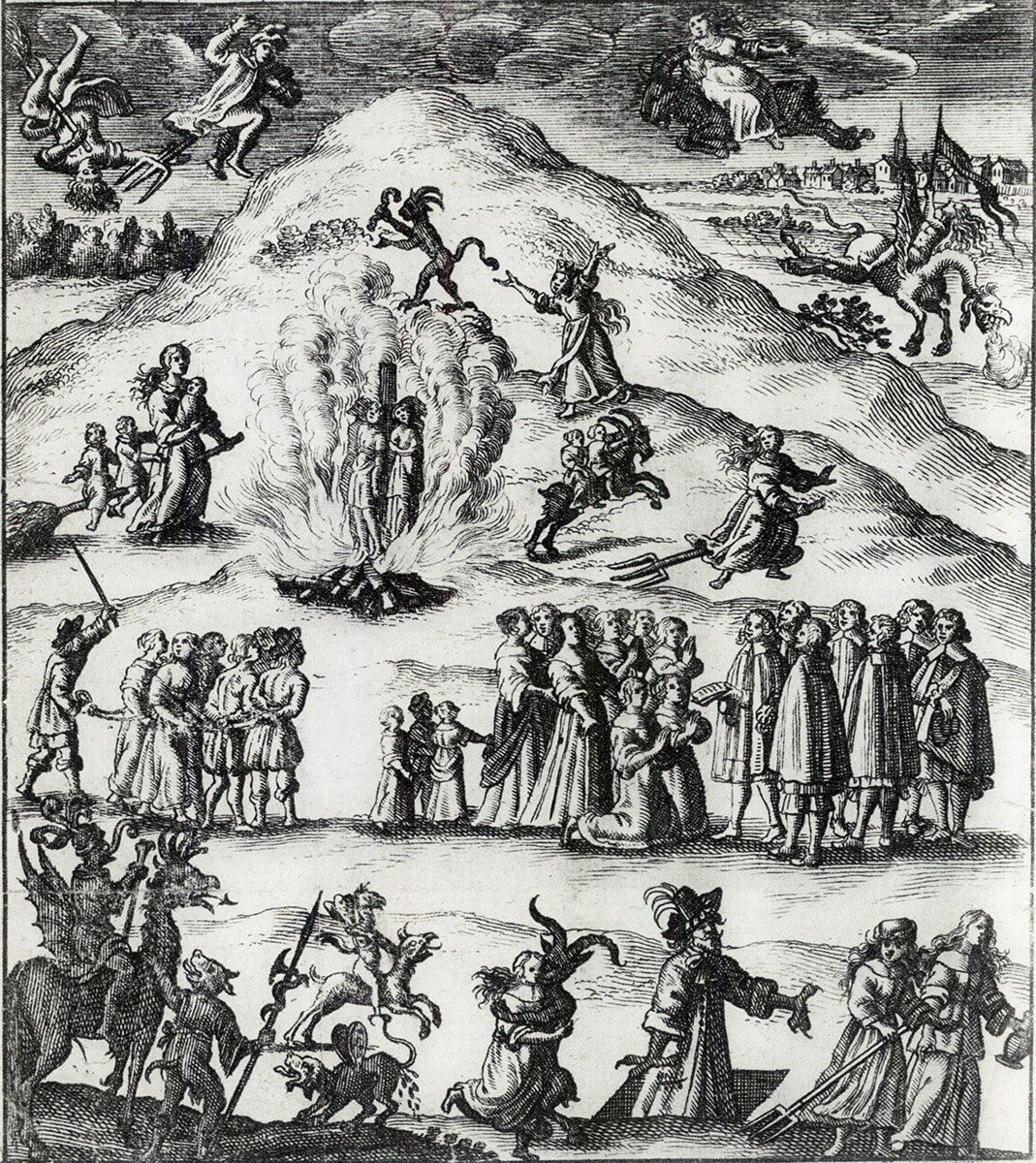

The Easter Hag tradition takes place annually on Maundy Thursday, during Christian Holy Week, which commemorates the washing of feet and, especially, the Last Supper. What better time for witches to stage their most important desecration of the year? As mentioned in texts as far back as the thirteenth century, witches flew to a mysterious place called Blåkulla to perform a sabbath and cavort with the devil. For hundreds of years, Swedes hid their household brooms and, to this day, light bonfires to scare witches away.

The folklore may be harmless now, but it wasn’t always so. In Europe alone, between the years 1450 and 1750, ideas about witches led to the deaths of as many as 100,000, and the victims were overwhelmingly women. A dark history lies behind our innocent tradition and those bonfires.

As an ethnomusicologist interested in the female tradition of Nordic herding music, I research the histories of women who worked the fäbods, or Scandinavian summer farms. Digging into their stories, I saw archival connections between some of these women and the most intense period of the Swedish witch trials, the years between 1668 and 1676 known to Swedes as “The Great Noise” (Det stora oväsendet). In following their lives beyond the fäbod, I found myself drawn into a bottomless void of grief. The following text is based on the preserved trial records concerning Kerstin Larsdotter.

The year is 1673. The place is the small village Hamre, Hälsingland, Sweden. It is a mid-September day in the season of harvest and Kerstin Larsdotter, a mother with her family, are hard at work, preparing for the upcoming winter. A terrible knocking at the door interrupts their labor.

Watching the solemn group of men who enter, it is possible Kerstin Larsdotter knew right away. She could not have missed the news from other villages. She has heard about the ordeals of torture and the flames of the pyre. They are hunting witches. Accused, she falls to her knees. Her husband and children embrace her as she cries out—“Perhaps I will never come home to you ever again.”

Kerstin’s hearing lasted four days. Fifty-four children and other suspects accused her. They declared that Kerstin had taken them to the witches’ sabbath, the Blåkulla—a place thought of as both physical and spiritual where the witches were said to copulate with the devil. One boy informed the court that Kerstin gave him food that was in fact a living snake, and, after eating, he could feel the snake twisting in his stomach. He testified that an angel appeared to him and said the only way to rid himself of the snake was to confess everything to the parish priest and that, after he did this, a snake crawled from his mouth. The boy’s parents and two other adults confirmed his tale.

One girl swore that at the Blåkulla, Satan spoke through Kerstin as serpents writhed about her neck. Other children told the court that black angels forced them to turn their backs to the altar and to curse the Holy Communion with evil words from a black book: “Cursed be the father, the mother, and everything that dwells on earth.”

Kerstin knelt and proclaimed, “I know nothing of this, my suffering does not help that fact!” But the children continue: Kerstin rode on the parish priest to the witches’ sabbath and forced them to take Satan’s hand. She answers these charges: “I do not know anything of this, please Lord in heaven, deliver me!” But the accusations of the children continue, this time in unison. At trial’s end, the judge sentences Kerstin to death by beheading, her body burned at the stake.

When reading the notes from Kerstin’s trial, I felt nauseous. I was sad and angry. But this sparked interesting thoughts: why were the witch hunts just a footnote in our Swedish schoolbooks? Why were these legal catastrophes and mass hysterias relegated to pop culture? Were we afraid to shine a light on past oppression and prosecution? That people might discover that these things haven’t left us? In continuously silencing an embarrassing past, were our government and authorities failing us?

I became sure that the silence should be filled, not just by academic research but through education and cultural preservation plans, because helping us understand why these things happen would help us see why similar things happen today. Prosecutions of whole ethnic groups continue. Islamophobia, LGBTQI+ phobia, racism, and misogyny still lead to violence and murder. The psychological mechanisms remain in place. My time in the archive made me surer than ever. The Great Noise was not just history, but heritage. A dark heritage that continues to make paths in our present.

The Spark That Ignited the Flames of the Pyre

The Great Noise occurred within a Christian context, so this is where I began my search.

In early Christian doctrine, general acts of a magical kind and destructive sorcery, or maleficium, were wholly separate things. It was not the use of magic that was criminalized, even if you had invoked the devil, but the destructiveness of its outcome. It wasn’t until the eleventh century that people accepted that the devil enabled all magic and that anyone who worked magic must have struck a pact with him. The clergy viewed these bargains as so severe that they threatened God’s omnipotent position and therefore the power of the church.

A systematic way to uncover both Satan’s work on earth and his conspirators emerged in the fifteenth century. In Europe, several writings on demonology and witches appeared, and due to the recent invention of moveable type, these were quickly shared. Published in 1487, The Hammer of Witches, or Malleus Maleficarum, by Dominican monks Heinrich Kramer (Institoris) and Jacob Sprenger, is but one example of these books, or rather manuals, that systematically argue for the existence of witches, then detail how to track down, try, torture, and execute them. It also explains why women are more likely to be witches than men: their flesh is lecherous and their minds feeble.

The 1500s brought a threat to the medieval church: the Protestant Reformation. This shows in ecclesiastical writings on the devil, demons, and witchcraft. Catholics accuse Lutherans and Calvinists of heresy, and reformative writers proclaim that Catholics are heretics who worship idols. A religious war erupted in Europe, which affected the church, worldly leaders, and, of course, the people. In this European context, the witch trials intensify in Sweden.

The Noise before The Great Noise: Demonology, Demonization, and Natural Disasters

In his 1555 opus vitae History of the Northern Peoples, Swedish Catholic Archbishop Olaus Magnus Gothus includes a few passages on witchcraft in Scandinavia. Following the rhetoric of his religious brethren, he demonizes pagan beliefs, as well as the Lutheran beliefs conquering Sweden. Olaus Magnus also points out the exact location of Blåkulla, where the Nordic witches were said to assemble.

The writings of Olaus Magnus were not directly related to the witch crisis in Sweden, but other works such as Laurentius Paulinus Gothus’s Ethicae Christianae (1617) and Ericus Johannis Prytz’s Magia Incantrix (1632) were. The latter stated clearly that maleficium, idolatry, and devil worship should be punished by death. Prytz echoes Magnus as to why women are more likely to become witches.

It is important to emphasize that the image of the witch as we usually portray her is not as old as beliefs in magic, nor is the belief in the broom as transportation. The seventeenth-century witch, developed while witch trials raged in Europe and colonial Massachusetts, is a blend of older traditions and ecclesiastical thoughts of malevolent female conjurers.

In the northern hemisphere, older beliefs survive in both early Roman Christianity and the Reformation. Tales were told of dark mares, bearing a resemblance to the Jewish myth of Lilith, that come at night to ride you in your sleep or eat your children, as well as treacherous and lecherous female entities who dwell in the forest.

During the witch hysteria of the seventeenth century, these beliefs were thrust upon those who practiced herbalism. Ideas of cunning women and men who magically cured the sick through herbs and ointments were reinterpreted and given threatening meanings as a strategy for demonizing folk beliefs. Only the church and health professionals could cure illness. For anyone else to try was to challenge church authority and power and, as the Lutheran church was so tied to the Crown, the king’s as well. The force that bound all subjects together should be the God of Christians alone.

But despite these processes of religious control, older ideas remained. Folk beliefs often work as a glue that holds a community together, and this is not something that can be dissolved so easily. The “witch crisis” arrived as a hot pot of clashes between older folklore and the new Lutheran religion. What these beliefs had in common was an ontological starting point: that outside our visible world existed a spiritual and celestial one that was equally real.

Another way the Lutheran church strengthened its power was by setting rules for the organization of the household. These were meant to resemble the hierarchy under which society was organized under God and, of course, the king, and placed the women of a household far beneath their husbands or fathers; a wife should worship her husband as she worshipped the Lord. Not doing so could get a woman in trouble.

It would be easy to wholly blame “the church” for the witch crisis, but things are never so simple. At the time of the great witch crisis, Sweden had gone through a period of climate change. Colder weather affected the amount and quality of the harvests, the fertilization rates among the cattle, as well as the quality of their milk. Outbreaks of plague afflicted the people, and poverty too, as Sweden’s rulers raised the population’s taxes in support of a series of wars. Poverty and desperation laid a good foundation for the witchcraft trials to come. An examination of court records reveal that some women accused during The Great Noise may have been singled out for far simpler reasons than witchcraft. Many of them came from families who were in legal conflict with their accusers over money.

Witch Trials in Sweden

Sweden’s witch trials did not begin with The Great Noise in 1668. Previously, regional medieval laws had already established the crime of witchcraft as one punishable by death. God’s law in Exodus 22:18 states: Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live. The first known witch trial in Sweden occurred in 1471. The first recorded execution occurred in 1550. So, trials were held before The Great Noise,but never with such vehemence.

In 1668, a young boy accused a shepherd girl named Gertrud Svensdotter. The boy stated he had seen her walk on water while herding goats at the fäbod, the summer farm. The parish priest, a deep believer of Satan’s works through witches, conducted a trial against her. She was sentenced to death on September 13 of that year. She was twelve years old. Later, the court altered her punishment and that of several other children to flogging. At the trial, Gertrud accused nineteen village women of attending the witches sabbath. They in turn pointed out even more witches. The accusations spread like wildfire, and hysteria ensued. This threatened to split both the local society and the central power. The Swedish government, understanding that a divided and socially infected society is more likely to not follow laws and pay taxes, quickly established a commission of priests and lawyers to assist local courts with the trials.

The commission traveled to the most witch-infested areas to “free the nation from the fury of Satan,”but the witch fever only increased, spreading to other parts of the realm. The trials on maleficium became a national catastrophe. To protect the children from the claws of evil and save the nation from God’s eternal condemnation, many village councils and courts pushed past accepted statutory procedure. Previously, torture was forbidden, but to execute a person, the Court of Appeal (Hovrätten) must confirm the sentence. Indisputable evidence was required, which meant a confession. Hence, the authorities deemed torture necessary. Also, the courts allowed children, once deemed untrustworthy, as key witnesses. Priests even paid some to testify, and the stories of children became the basis for many death sentences.

The culmination of The Great Noise occurred in Torsåker, in the region of Ångermanland, where, on October 15, 1674, seventy-one people were beheaded and burned at the stake. Women numbered sixty-five of them, every fifth woman in the parish. In 1676, the fever reached Stockholm, the capital. There had always been doubters in the church and among worldly men in power, but now several voices were raised against the witch accusations. Suddenly, a majority began to question the truthfulness of child witnesses, several of whom later confessed that they had lied. For that, they were executed. This would spell the end of The Great Noise. A few trials took place in the 1700s. In 1858, a priest in Dalarna accused a group of witchcraft, but they never came to trial. The Swedish state silenced these accusations as they brought embarrassment to the government.

In total, about 300 people, mostly women, lost their lives in Sweden during The Great Noise. From 1550 to 1668, the period directly before, the authorities executed 100. These numbers are based on records still preserved. There were more, but their names and deaths are lost to us.

Witch Trials as Heritage?

Now, what do we do with this dark and difficult part of our history that caused so much suffering? How do we manage the memories of such ordeals?

In Sweden, we meet the suffering by basically playing around with the Easter Hag. Since the 1800s, she is the tradition. She has become our heritage, not the events which lie hidden in her background. Do Swedes do this to cope with a difficult recollection? Or to reminisce over the times before the witch trials when spells were not an evil act and the cunning women of the forest an important part of our healthcare system? Or do we dress our children as witches because we prefer to make quaint a wildness we still secretly fear?

I believe that the Easter Hag is a combination of these things. She is both innocent and cunning, a malevolent woman who may scare away evil beings, as well as the memory of the healing herbalist who made no pact with the devil for her abilities. But what do we do to get closer to the darkest part of her heritage?

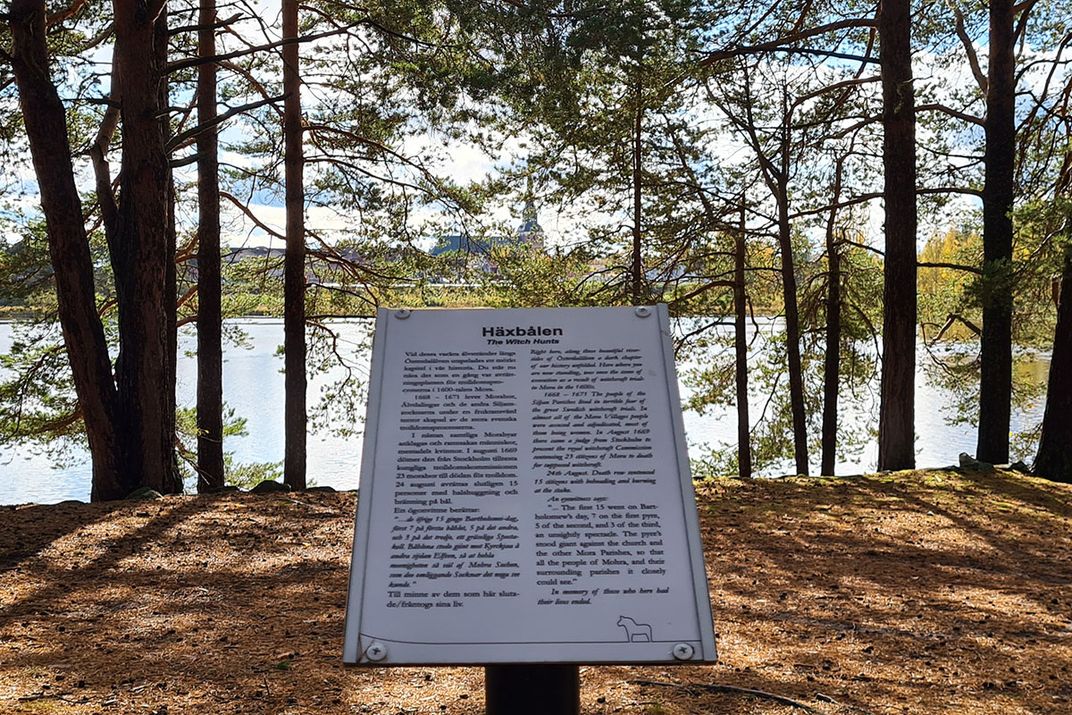

There are groups that make an effort to remember those who were forgotten. Local communities and culture workers arrange events and theatrical performances that tell the stories of the executed. This summer, in order to educate visitors, at the suggestion of its citizens, the town of Mora inaugurated a memory stone to those executed there. On the stone, you can see the names of those who were beheaded and burned at the stake, as well as the names of those who were sentenced to death but escaped this fate. The last words on the stone spells out: “peace over their memory.”

Remembering the witch trials can be a feminist action. Factions of New Age pagans celebrate magical beliefs as heritage, sometimes as an act to shine a light on the witch prosecutions as femicide. The Swedish National Heritage Board has marked on maps the places where pyres burned and you can visit.

But this is not enough. We should fill the silence more broadly. Enough would be a public discussion of even our darkest cultural stories. Here, we need to step away from the misogyny that landed these women at the stake in the first place—misogyny that takes place everywhere, even in authorized heritage discourse.

Until recently, most modern constructions of heritage were based solely upon positive narratives chosen by authoritative scholars and institutions. This authorized discourse set the agenda, stipulating what traditions we should value and hold worthy of the name heritage. Those who control the conversation ask, how can we present to the world as heritage anything that has brought us shame? Heritage should be about pride, they say.

As a result, stories are routinely silenced or completely distorted to fit approved paradigms. Difficult and problematic things, like prosecution, slavery, oppression, colonialism, and genocide are not considered heritage, just parts of our history that we place in brackets because they are sources of shame. There are heritage sites that exist because of tyranny and cruelty, that reflect, for instance, the enactments of authoritative forces upon multicultural folk traditions or the “other.” In contextualizing these places, those in power are fully capable of transforming the tombs and burial grounds of cultural extermination into treasures and trophies.

In heritage discourse, the histories of marginalized peoples are as oppressed as the people themselves, because heritage is so often forged to preserve power and maintain precedence. The story of the women in the Swedish witch trials serves as an example. We present The Great Noise as history, not heritage. It is just not something to be proud of. We make of the Easter Hag an innocent, positive tradition, despite the dark events she signals.

Our government and society have a responsibility here, as does the education system. Let us expand the plaques in the woods, return to the victims their names, make women’s history, with both its narratives of success and oppression, a mandatory element in the curriculum. Let us also expand women’s history so that it goes beyond the privileged. Let us read about women who exist only in archives, accessible only to those who hold a researcher’s identification card. Let us educate ourselves in the history of the prosecuted and oppressed, read about why this was so. Paying attention can teach us why these things still happen. Let our dark stories become heritage.

As Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel stated: “The executioner always kills twice, the second time with silence.”

Jennie Tiderman-Österberg is an ethnomusicologist at Dalarnas museum in Sweden, a PhD student in musicology at Örebro University, and a singer.

The author would like to thank Anna-Karin Jobs Arnberg and Sebastian Selvén at Dalarnas museum for discussing the themes of this article, as well as for proofreading. Thank you Anneli Larsson at Mora Kommun for helping out with pictures, as well as being responsible for the memory stone in Mora.