SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

A Rural Pastime Grows Community at the World Pig Championship

No one knows who created Pig, a local traditional card game, or who gave it its unusual name.

:focal(600x429:601x430)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/22/73/2273444a-06f8-43da-af2c-ee1bf0ecea23/world-pig-championship-crowd.jpg)

“If you’re here for any other reason than to have a good time, you’re here for the wrong reason,” Jim Buck bellowed to an eager crowd of competitors. Wearing one of his signature bucket hats—this one a floral print—Buck stood in the middle of the wood-paneled back room of the York Country Store in Pall Mall, Tennessee, and thanked the crowd for coming to play in the 2023 World Pig Championship.

No one knows who created Pig, a local traditional card game, or who gave it its unusual name. In this area of Tennessee, a two-and-a-half-hour drive northeast from Nashville near the Kentucky line, the game has been passed down through generations. Here, backroads wind through tranquil countryside cradling a cluster of small rural towns. Pig lives in three of these communities: Pall Mall in Fentress County, nearby Byrdstown in Pickett County, and across the border in Albany, Kentucky.

Without many other options for entertainment, Pig became part of daily life, a cheap pastime requiring only a standard deck of cards. Jeff York, owner of the York Country Store, sat behind the counter and reminisced about years past when all the local stores hosted games of Pig. He remembered that older men played all day while the younger men joined after leaving their work in the fields. One night he was playing with other residents at a store, and a man came in and left his truck running in the parking lot. But after he joined the Pig game, he must have forgotten about his truck because he played all night. When he came out the next morning, he discovered it had run out of gas.

Now locals play Pig at the York Country Store on weekend mornings, but Buck, who used to spend days off from school sitting on a soft-drink crate in a local gas station playing Pig, knows younger players are needed to ensure the tradition’s future. In today’s society where options for entertainment abound, he lamented that the old way of life has changed.

“People do not need other people for entertainment,” Buck recognized.

York agreed: “There’s not much anymore other than ball games or something like that that people go to that’s a community thing, and that’s what we need more of.”

This was York’s first year hosting the World Pig Championship. Every other tournament was held at the nearby Forbus General Store, a local institution serving milkshakes and burgers and still heated by a huge wooden stove, but it is under new management. The tournament was canceled in 2021 and 2022 because of the pandemic and Buck’s recovery from a car crash. This year, on February 25, 2023, York was happy to donate the use of his back room. “It’s really good for the community... and it’s just good to have everybody here.”

As an archive of community history, York Country Store is a fitting place to hold the main tournament of such a local tradition. The store and restaurant sit next to Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park, honoring the area’s most famous resident, a World War I hero credited with capturing over a hundred German soldiers. York, the sergeant’s grandson, honors his memory. Part museum and part business, the store walls are festooned with newspaper clippings and family photos, and a case of letters and memorabilia sits among the snacks and knick-knacks for sale.

Buck, a former teacher and now an elementary sports coach whose favorite Christmas hobby is playing Santa at area events, has become a Pig ambassador, struggling to promote and preserve the game and his community. He was inspired to organize a World Pig Championship after witnessing a Monopoly board game tournament in Las Vegas. The rules had never been recorded, so he wrote them down and copyrighted them. At the first championship in 2001, 32 people showed up to play. Over the years, this free tournament, always held at noon on the last Saturday in February, has attracted people from all backgrounds; some years have seen over 100 competitors.

It’s apt that Buck was inspired to start the championship in Las Vegas. Pig would be at home among the city’s games of chance and skill. Part of the game is “luck and gut,” he explained. “And it’s offensive.” Similar to Rook, the goal of Pig is to be the first pair of partners to reach 52 points. If a team loses 52 points, the other pair automatically wins. According to the official rules, players use all 52 cards and one joker, but in practice this varies depending on location; players in Byrdstown don’t use any jokers while players in Albany use two.

Strategy is essential in Pig. A player must consider what cards have been played, what cards their opponents are likely to have, and what cards their partner is likely to have as they vie to place the highest-ranking trump card on the table and “catch,” or earn, all of the points of those cards for their team. They want to play a Pig, the number five card of the trump suit worth the most points, only when they think their partner, and not their opponents, will catch it.

“Who needs a card? Who needs a card? Card? Card? Card?” blared Buck like an alarm, sounding the start of the twenty-first World Pig Championship. Trying to make himself heard over the din of excited chatter, Buck handed a playing card to each of the forty-five competitors. Ingenious in its simplicity, this is Buck’s way to corral the players to tables and match them with their partners. Each table has one playing card on it. Players look for the table with the same number or face card as the one Buck gave them. Of the four players assigned to one table, the two holding red cards are partners, and the two holding black cards are partners.

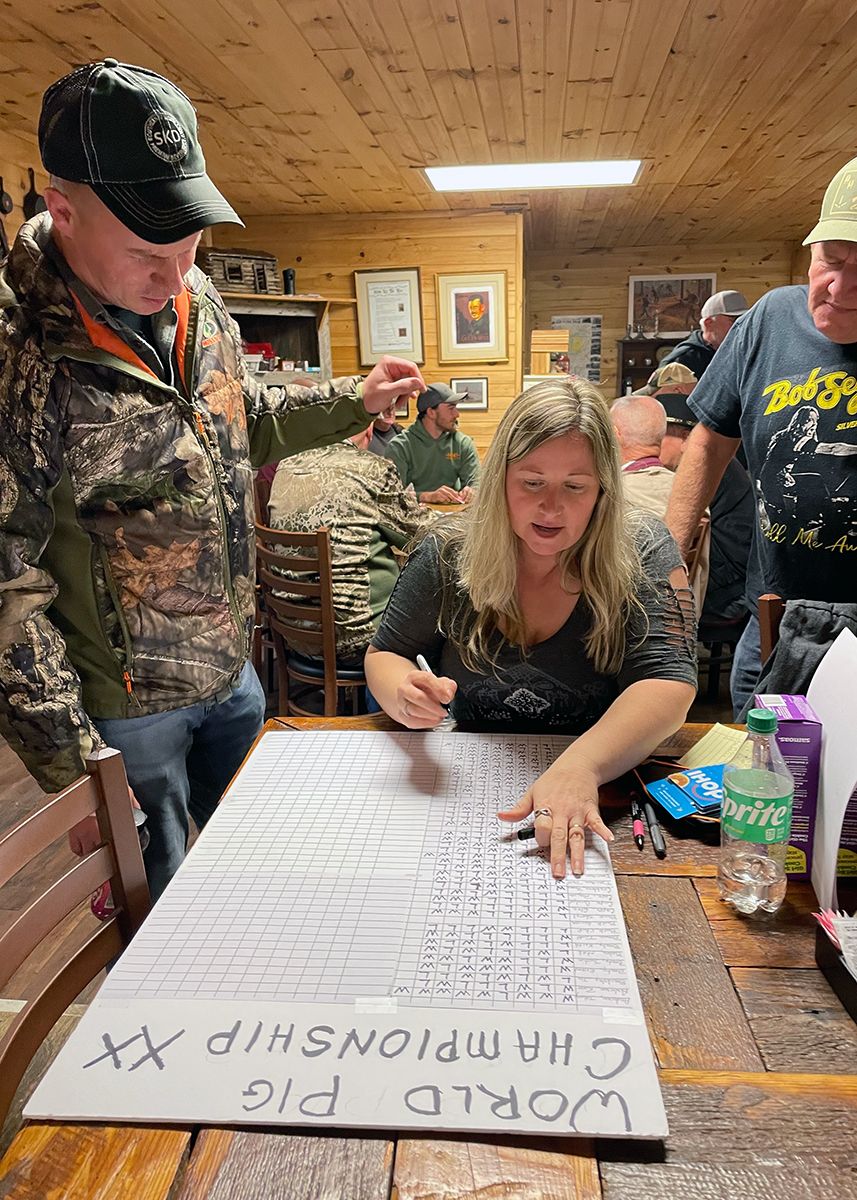

After completing a game, the player who kept score must report to Becky Wilkins in the middle of the room. Wilkins has volunteered her time as scorekeeper for almost a decade. “I enjoy seeing everybody, especially when it was an every-year thing,” she said. Wilkins, a Pig player herself, notes the loss or win for each person on a poster board. At the end of the day—Buck doesn’t start a new game after 5 p.m. —the player with the most wins is the champion.

While everyone is playing to win, the real draw of the tournament is the camaraderie; fellowship is built into the tournament. Since every player must draw a different card before each game, it’s almost guaranteed that no one will play with the same group twice, which encourages players to meet everyone. Because all games must finish before anyone can start a new one, this leaves plenty of time to socialize. Even those who don’t want to play come to chat and spend an afternoon among friends.

Scanning the room, Buck mused, “If one person had a flat tire here, everybody here would be breaking their neck to help change it… They’re neighbors—the way it used to be, and it’s still here in some places. But we actually take it for granted. We really do.”

It helps that no money is at stake; Buck prefers to give away prizes by random drawing. This year, York donated free meals from his store and a stack of Girl Scout Cookie boxes he bought, trying to help the local troop sell out. Instead, the game winner gets bragging rights, and Buck adds the champion’s name to a plaque.

Rick Vitatoe appreciates this aspect of the tournament. For him, the best part is the hospitality. “No one gets upset about it,” he said. “You’re not betting money—it’s just fun.” Vitatoe, originally from Pickett County, has lived in Bluffton, Indiana, for over thirty-five years. He’s attended most of the tournaments and won in 2019. He even rescheduled work meetings so he could attend this year’s tournament.

Hal Boles, also originally from Pickett County, agreed. “The people here are what makes it so fantastic.” He has lived in Washington, D.C., for over fifty years and has attended most of the tournaments. The week before this tournament, he was cleaning out old business files and was surprised to find a copy of Buck’s Pig rules tucked among the papers. Taking this as an omen, he made the nine-hour drive to attend. “I literally wouldn’t miss it for anything—as long as I can get behind the wheel and drive down here.”

Even if someone can’t make it to a Pig game, Buck will bring Pig to them. He believes, “Anybody, anywhere… if people could just see it, everybody’d want to know how to play.” At this tournament, he arranged to teach the Girl Scout troop selling cookies in front of the store, and when two couples from Georgia wandered in, he offered to travel to their hometowns to teach them. He regularly teaches Pig at home for free as well. Because Pig is a game of statistics, he once taught a local high school math class and has given lessons at the local senior citizens center.

In this way, Buck uses Pig as a tool to strengthen local ties and bring newcomers into the fold. Tim Zabawa and Bob Hofmeyer are recent Pig converts. Zabawa, originally from Nebraska, and Hofmeyer, from Michigan, met after they and their wives retired to the area a few years ago. After reading about Pig in the local newspaper, they attended lessons taught by Buck and played in the last tournament. They returned for the championship’s comeback this year.

“Jim Buck is the driving force behind this tournament and the game itself, I think,” Zabawa noted.

At this year’s championship, Buck reserved a table for anyone wanting to learn the game. While others competed for the title, he offered lessons. Austin Andrews, a DJ for the local radio station and originally from Los Angeles, wanted to learn so he could teach his family. Lorelei and Bob R., who moved to the area two years ago from Hawai‘i, observed. About their chosen community, Lorelei shared, “I love it. The people here are very, very good people.” After they heard about Pig from a neighbor, they wanted to see the game. “We’re in Rome, so we’re being Romans—or we’re in Pall Mall, so we’re being Pall Mallians,” she joked. Before they left, Buck instructed them to call so he could teach them. Bob remarked, “Hopefully, next year I’ll be down here playing in it.”

Chris and Kim Marsh from Chattanooga, Tennessee, also learned to play from Buck during the tournament. They hadn’t originally planned on attending; they were visiting the area and wanted to hike but decided to stop in and wait out the rain. When asked how they met Buck, Chris quipped, “How can you not? If you ask how to play, he hears you— Yeah, you’re going to meet Mr. Buck.” After they left, Buck announced, “I guarantee you those two will be here next year.”

“One game for all the marbles! Everybody gather round and watch!” Buck directed.

After five hours and nine rounds , two players were tied, having won each of their games but one. They would have to compete in a playoff to determine the champion. In a back corner of the room, everyone huddled around the players at their table, and Vitatoe and Wilkins’s husband joined to make the required four. Never completely silent, the noise from the spectators fluctuated, tired lulls swallowed by jokes, questions, and score reports from Buck and onlookers.

At last, someone shouted, “We have a winner!” launching Pall Mall local Johnny Anderson’s reign as the 2023 champion. The crowd marched outside into the dusk and gathered in the parking lot to watch York and Anderson pose for photos holding the plaque that will soon bear Anderson’s name.

After hearing from attendees that they would like more opportunities to play, York told Buck he could host a Pig night each month. “We’re open to anything at the store to help people come together and visit,” York said. “We try to make it a community thing or a gathering place.”

Buck believes all communities need more activities like Pig. When asked what would happen to the community if it stopped playing the game, he made a vow.

“I’ll never know because I won’t let that happen.”

Maggie Gigandet is a Nashville freelance writer focusing on the outdoors and people with unique passions. She loves exploring her home state and learned about Pig after seeing the champions’ plaque at Forbus General Store.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5a/3b/5a3b496e-dd9d-405d-9532-246c0fc311fe/world-pig-champions-plaque.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/5b/035b96c3-4882-461e-bc66-c4897ba98bf0/world-pig-championship-2023-winner-1.jpg)