SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

The Millville Rose: Artifacts of Whimsy and Art in Industry

The “Millville Rose” represents the refined skills of factory glassblowers who toiled in an industry in which they had little say in what they made.

:focal(600x400:601x401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cc/61/cc61c542-d1a6-4ed3-8f3c-d5776b81f88b/millville-rose-pink.jpg)

As we make the turn onto Route 47 in southern New Jersey, my attention turns to the collection of decaying buildings glaring down at us. I recall my family telling me, “Millville hasn’t been the same since the factory closed.” My grandmother, Bernice Wangstrom, drives the car. Back straight, fingers wrapped around the wheel, she has eyes only for the patchwork road. She pays the old Wheaton Industries factory little attention like most people driving by—it’s been shut down for eighteen years. But I can’t stop looking at it.

Patterns of orange rust and graffiti tags sprawl across the building where glass workers once made nail polish bottles, perfume bottles, liquor bottles, and scientific glassware for Avon, Revlon, Jim Beam, Old Spice, and Schiaparelli. Railroad tracks where trains once delivered raw materials and hauled out boxes of decorative bottles still line the ground. For most of my life, the facility sat abandoned, but at my grandparents’ all-American home, where I spent each summer, a legacy of the South Jersey glass industry remains.

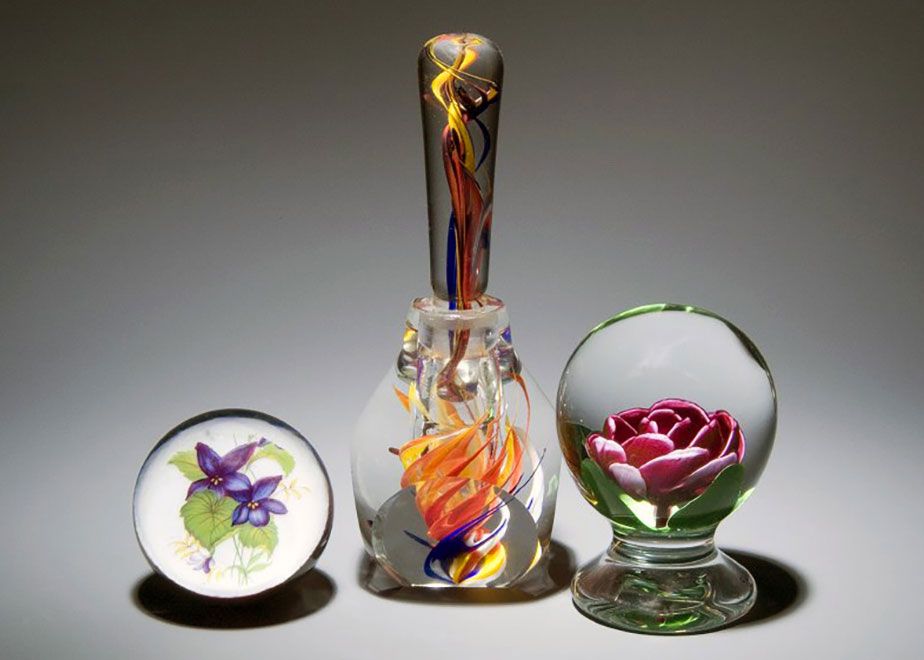

Sitting on my grandparents’ living room shelf among Russian nesting dolls and framed family photos rests a glass paperweight shaped like an orb. Beneath its clear surface are the chalky pink petals of a blossoming, lifelike glass rose. The “Millville Rose” represents the refined skills of factory glassblowers who toiled in an industry in which they had little say in what they made. Through these charming yet unassuming art pieces, made in their spare time, Millville glassblowers explored the boundaries of their craft and created a tradition they felt worthy of passing down.

For most of the twentieth century, a great many Millville residents worked in the glass industry, including my mom’s side of the family. They were machinists, mold makers, packers, and office workers. Although none of them learned glassblowing, my grandfather, Robert Wangstrom, recognized something in the Millville Rose.

“Bobby Grablow, at the time, was into fixing and selling bicycles, and Pop Pop wanted one of those Millville Rose paperweights,” my grandmother says, rummaging through drawers. I can hear her pressing the phone against her good ear as she looks for some of the glass she and my grandfather collected.

“And they traded—a bunch of old bicycles for a Millville Rose.” Grablow was one a handful of men working with my grandfather in the Wheaton Industries mold shop who learned glassblowing and made the rose. He was muscular from wrestling, perfect for carrying the weight of glass. “Bobby didn’t make them to sell, I don’t think.” This exchange took place in the 1990s, but the tradition of the rose goes back much further.

Gathering Glass

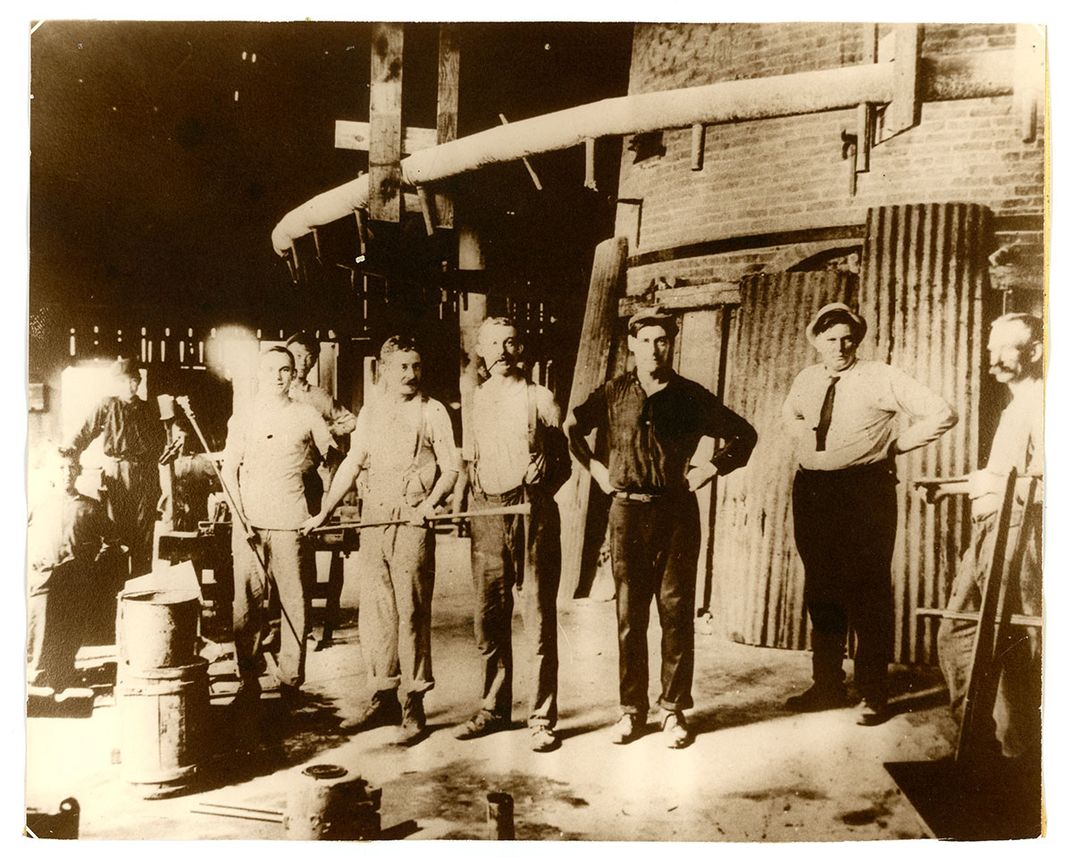

Located along the Maurice River, the Whitall Tatum Company opened in 1806 and became the largest glass company in town, predating Wheaton Industries by eighty years. Many of the glass factories in South Jersey drew from the natural resources along the waterways, including silica sand, to produce glass.

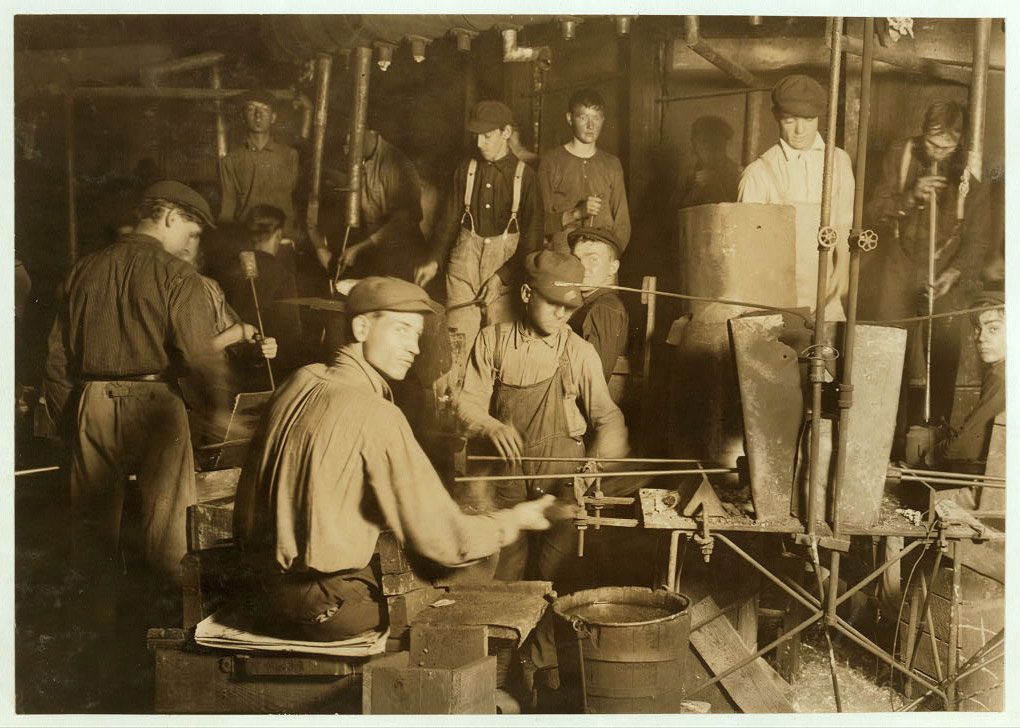

During this time, the United States lacked homegrown talent. Instead, the industry relied on immigrant glassblowers from Germany, England, Sweden, and Italy. Glasswork was viewed as an invaluable trade that took years to learn—something still true today.

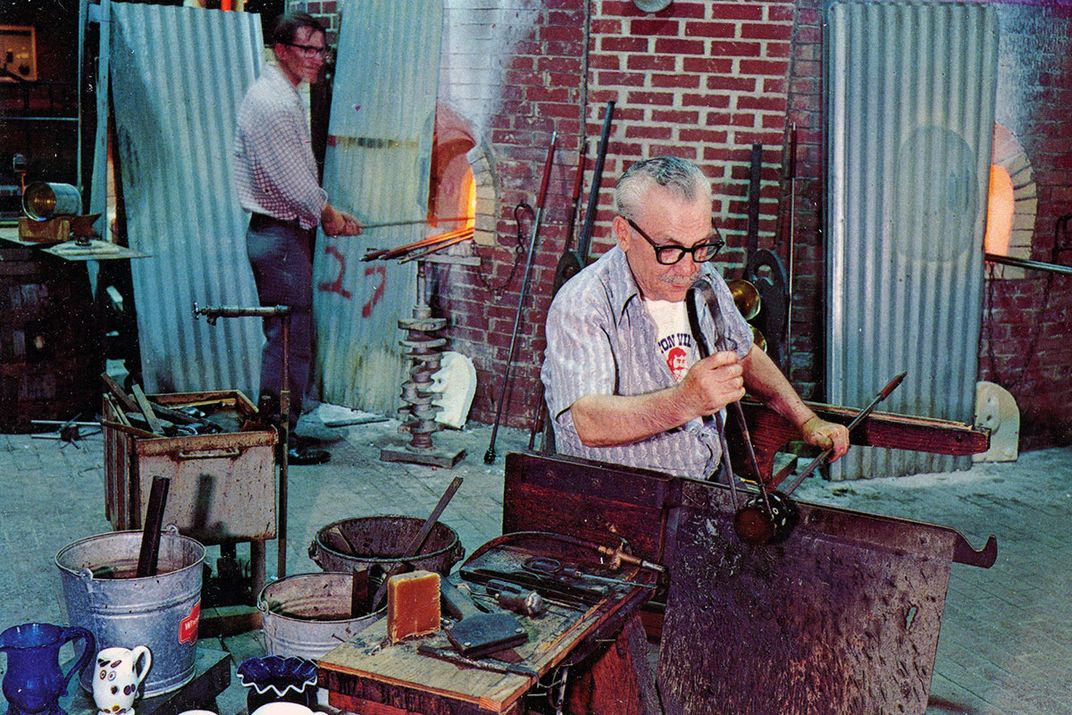

Glassblowers face heat radiating from furnaces reaching 2,000ºF. The glassblower sticks their blowpipe into the furnace to gather the molten glass using a practiced turning motion. As the pipe is so long, a couple pounds can feel like a couple dozen. Maintaining the spinning holds the shape of the glass. Either the glassblower, while holding the blowpipe, or an assistant can shape the glass with an array of tools, pressing against or inside the molten glob. Despite the intense environment, the glassblower needs to fill their lungs with enough air to blow down the length of the pipe, giving shape to the glass. All this must be done quickly, before the glass begins to harden.

It is a little miracle that even with their muscles straining, their backs bent, sweat rolling into their eyes, glassblowers can produce things delicate and beautiful. The process takes a toll on the body, and glassblowers tend to develop favoritism to one side. When I spoke with glass artists from Wheaton Arts, a nonprofit offshoot from Wheaton Industries, some revealed physical challenges they face.

“I’m severely left-eye dominant and the action is [affecting] the right side of my body,” said Alexander Rosenberg, the current glass studio director and a former competitor on the Netflix glassblowing show Blown Away. “I tend to hunch over in an exaggerated way to see clearly what’s going on.”

Don Friel, a seventy-two-year-old glassblower, is one of a handful of people who can make the Millville Rose. Friel developed a knee problem, so he prefers tight workspaces. Keeping to these contained areas means he doesn’t have to walk long distances between a furnace and tools, further straining his knee throughout long sessions.

There is extreme heat, noise, and brightness, but the artists who work with glass work with it for the same reasons other artists work in their own mediums: it’s the best way they can express themselves.

It is a process that cannot always be done alone though, and the early American glassblowers were familiar with working in teams to meet production quotas. In their downtime, they would experiment with the glass, altering techniques to improve their skills.

“The whole seeing, learning, trying, failing, and then getting better at it has been part of the glass field, I’d say, forever,” Friel surmised in his crisp manner of speaking.

This trial and error likely led to the boom of “whimsies,” objects that glassblowers made in their free time to exercise creative freedom and claim bragging rights. These whimsies often took the form of pitchers, vases, canes, and animals they could share or sell on the side. Wherever glass companies cropped up, whimsies followed.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Whitall Tatum introduced new glass colors to its bottles, jars, and vials. That’s when workers began creating new styles and developing techniques for paperweights, culminating in a style associated with the area.

“Nowhere else in the world [were] they even trying to make these things on their lunch hour,” Gay LeCleire Taylor tells me, passion punctuating every word. She started studying paperweights in the 1980s through Wheaton Village (the predecessor to WheatonArts), where she later became the curator and director of the Museum of American Glass.

As one story goes, the Millville Rose paperweight was first created by Ralph Barber. In fact, it is sometimes referred to as the Barber Rose. After immigrating from Manchester, England, he eventually started working for Whitall Tatum.

Perhaps, while going through the monotonous motions of blowing glass bottles, he began to long for his flower garden at home. Or it could have been a way to claim bragging rights as he watched workers around him develop new styles and techniques. Whatever the reason, he went through trial and error to perfect his technique.

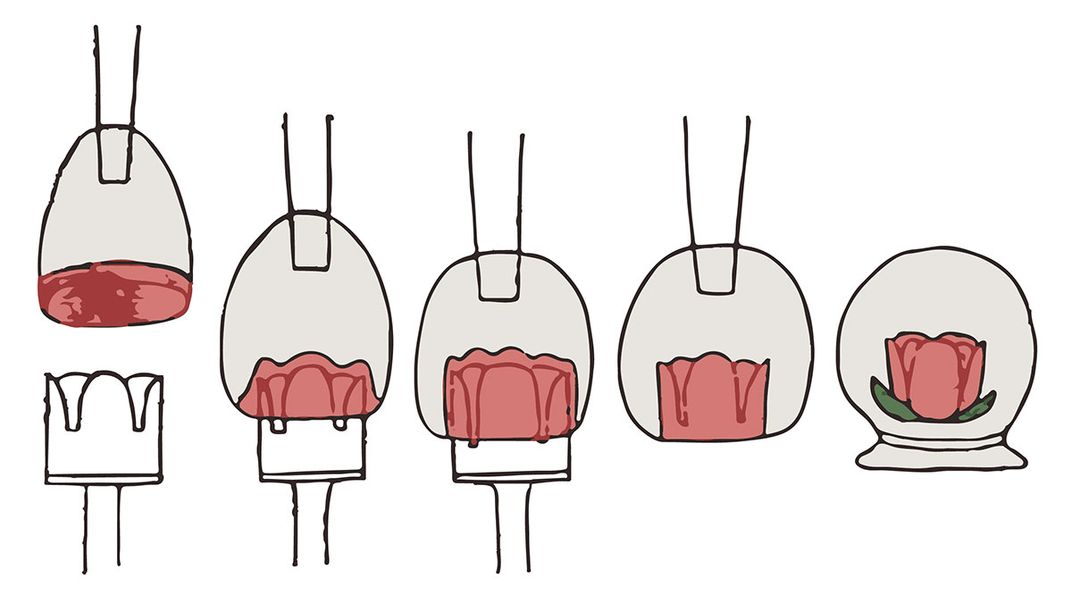

He developed a metal “crimp,” a tool used to press a design into glass. Adding color to the bottom or side of a clear glass orb, Barber pushed a crimp with a many-petaled rose design through the color and into the molten glass. With the design pressed into the orb, the flower could be manipulated into blooming.

Don Friel tells a slightly different story. He puts Barber in conversation with a Swedish immigrant imagining the creation of the Millville Rose as a collaborative effort. “Men who saw them went home and made their own crimps and started exploring,” he says. “Then, other men in the factory saw that. So, over the years the rose knowledge was passed down from generation to generation of glassblowers.”

Gay LeCleire Taylor agrees with Friel’s collaboration model but credits all the Whitall Tatum glassblowers. These explorations into new techniques were encouraged by glass companies as it helped workers hone their skills.

Still, the men who developed and perfected the crimping method preferred to keep it to themselves. The problem with keeping a practice secret is that it has the potential to die.

By the early twentieth century, the livelihoods of the workers were threatened. In 1903, in Toledo, Ohio, a glassblower engineered a machine that could produce sixteen bottles per minute. It could produce more bottles in an hour than a team of glassblowers could produce in a day. Whitall Tatum followed suit and created a department to develop similar technology.

The workers tried to sabotage it. “At night, they would pour water on it and do all kinds of things because they knew this machine was going to end it all,” Taylor says. By 1920, machinery replaced the need for industrial glassblowers and their teams. From then until the 1970s, Millville glassblowers continued making the rose in their backyard shops, some to keep, give, or sell.

Eventually, some of the Millville glassblowers turned to another glass company to house their secret.

The Passing on of the Millville Rose

In the 1960s, Frank H. Wheaton Jr. became the third in his family to head Wheaton Industries, taking over from his father. On a trip to the Corning Museum of Glass in New York, he came across glass bottles, whimsies, and more originally produced in Millville. Soon after, he established Wheaton Village to celebrate glass as an art form and began sourcing collections and artists from the area.

Wheaton Village provided local glassblowers a place to continue the tradition of the Millville Rose and its closemouthed technique. The community culture they created provided a way for glassblowers to share in their lived experiences and how they best expressed themselves. The Wheaton Village glass shop opened in 1972, with experienced glassblowers William Valla and Eugene Crabtree on staff to hold demonstrations and discuss the trade.

Friel was first introduced to Wheaton Village through a program at his college. When he met Valla and Crabtree they were in their sixties and seventies, respectively, and accustomed to keeping what they knew to themselves.

“That was common back in the old days because you were only as valuable as your knowledge, and a lot of these guys would move from factory to factory. The better their skill set, the more money they would make,” Friel says, recounting his first impressions of the men.

In the 1990s, a new generation of Millville factory workers learned to make the Millville Rose. Wheaton Industries offered to give their employees time to play with the glass in exchange for narrating demonstrations. Working in the Wheaton mold shop together, mold designer Jack Choko encouraged Robert “Bobby” Grablow—who would later trade with my grandfather—to take up glassblowing and make Millville Roses. My grandfather recalls Choko by laughing, painting him as a man with a perpetual positive attitude. He was not someone who would give up easily.

So when Choko was dying from a long-term illness, he gave Grablow his biggest crimp. Like the glassblowers before him, Grablow came to the glass studio during his lunch hour to work on his roses and narrate demonstrations. As Friel remembers it, Grablow produced antique-style rose paperweights that “he got pretty good at.”

Over the years, Friel accumulated many crimps from people who had inherited them. Made from plaster and tomato paste cans, each is unique with small design details by their makers. Learning to use the crimps wasn’t easy though, as Friel observed. It wasn’t information freely doled out. “You earn their respect, then all of a sudden they would open up the floodgates and give you all the information you wanted,” he says.

Some glassblowers didn’t want others participating in the tradition of the Millville Rose until their time was done. In the 1980s, Friel started making the rose, having been handed a crimp by older glassblowers, Anthony “Tony” DePalma was upset. DePalma had been an assistant to the Swedish immigrant associated with the creation of the rose technique and later became one of the names most associated with the paperweight. He had wanted Friel to wait so he could teach him toward the end of his career. But Friel, then in his thirties, told him, “Tony, I can’t afford to wait until you’re retired. You might live to eighty.”

By the 1990s, Frank H. Wheaton Jr. was forced out of the company by a faction of the fourth generation in the family, who many blame for the downfall of the factory.

“Mr. Wheaton could make a lot of mistakes, but he kept jobs in Millville,” says LeCleire Taylor, sadness threading through her words.

The factory shutdown irreparably changed the town, forcing some to retire and leaving thousands unemployed. After nearly two decades, the factory complex is in the process of being demolished, meeting the same fate as many other South Jersey glass factories.

The timing isn’t clear, but by the end of the twentieth century, much of the secrecy surrounding the Millville Rose technique diminished. There aren’t many glassblowers in Millville anymore, but the artists and curators at WheatonArts, formerly Wheaton Village, keep the tradition of the Millville Rose alive.

Return the Blowpipe to the Furnace

Now, Friel makes Millville Roses about once a week, working to produce new collectibles and pushing the limits of what can be done with the paperweight. In doing this, he reimagines how the rose might look and carries the memory of the no longer secretive technique.

He says the longer he goes without making the roses, the harder it is to remember. He’s trying to teach someone who is a frequent collaborator. “I figure when I stop, I’ll probably leave my crimps, and then if he wants to pursue it, it’s up to him.”

The tradition continues since Ralph Barber’s time: generations of glassblowers in Millville taking an interest in the paperweight, creating community, and claiming something for themselves. Along with WheatonArts, the Millville Rose is the remaining symbol of the industry that once defined the town for generations, a colorful objet d’art that rose amid the dirt and sweat of the factories. Now, it’s just a matter of waiting to see if someone will pick up a crimp after Friel and his generation. Even with the collapse of the glass factories in the area, there might be a rose crimp on a shelf fueling a child’s imagination.

I would like to dedicate this article to my grandfather, Robert “Bob” Wangstrom, who recently passed away and whom without, I may never have known such a beautiful art. What precedes this was written before his death, capturing a moment of his life remembering what he bore witness to from the sidelines. Most of this process included sarcasm and bitter laughs, but I wanted to highlight to him one of the many significant parts of his life.

Alexandra Sikorski is a writing intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a graduate student in the Master of Arts in Public Anthropology program at American University. When she isn’t researching contemporary witchcraft, she enjoys dissecting material culture and design.