Talking to Children After a Traumatic Event

As details about traumatic events unfold in the news, it is important for families to navigate these conversations with young children with care.

:focal(475x875:476x876)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/GettyImages-1237929985.jpg)

This is part one of a series on talking with children about traumatic events and their root causes. Part two addresses the importance of making this an ongoing conversation with children.

As Smithsonian educators working on the National Mall, just steps away from the U.S. Capitol Building, the January 6th attacks are very close to home. As educators who work with young children, we empathize with parents and caregivers trying to process these violent and traumatic events. How can adults find the “right” words? How do you talk to children about traumatic events?

Unfortunately, there is no manual or simple answer, but we can offer guidance and resources based on our training, expertise, and experiences talking to children about moments in history as museum educators and parents.

Pause and reflect.

Before reacting, pause and reflect. How are you feeling? You are likely processing and feeling many emotions, and will continue to. Acknowledge these feelings and take time to practice self-care and reflect on your own. It’s important for children to know that adults have emotions too, and it’s okay to show them.

Take time to consider whether this conversation is new for you and your child. How often do you talk about current issues? Know where you’re starting and acknowledge that your child may have little context (or a lot of context) for processing what’s happening.

Begin with questions.

With a few simple questions, you’ll find out how your child is feeling and what your child knows – or thinks they know. Whether or not you intend for your child to see or hear the news, they’ve likely picked up that something important is going on in the world. Children observe our facial expressions and body language as we look at our screens. They overhear conversations and TV chatter and notice the tone or emotions in voices. And they’re seeing the small images we swipe past on our phones or the big ones showing over and over again on TV.

Within a short period of time, their young brains have tried to make sense of the little bits and pieces of words, images and emotions they’ve absorbed and observed. When we ask questions, we gain a better understanding of where we need to begin the conversation.

Invite your child to ask questions. Children also need time to process their thoughts and feelings, so be open to questions that may arise later. Children often work out and verbalize difficult ideas while at play, so take time to observe and listen during their playtime.

Give honest, but simple answers.

With an understanding of what your child is feeling and thinking, you can begin to give information that clarifies what happened and calms your child. Adults tend to either over-respond or avoid responding. An over-response risks providing too much information and inserting adult emotion about current events. On the other hand, silence is harmful as children may imagine worse scenarios and learn to keep their feelings and fears to themselves.

Children need concrete information, and also deserve the respect of an honest and age-appropriate conversation. Use concrete language to describe what happened clearly, but simply enough for a child to grasp.

Let your child know they're safe and loved.

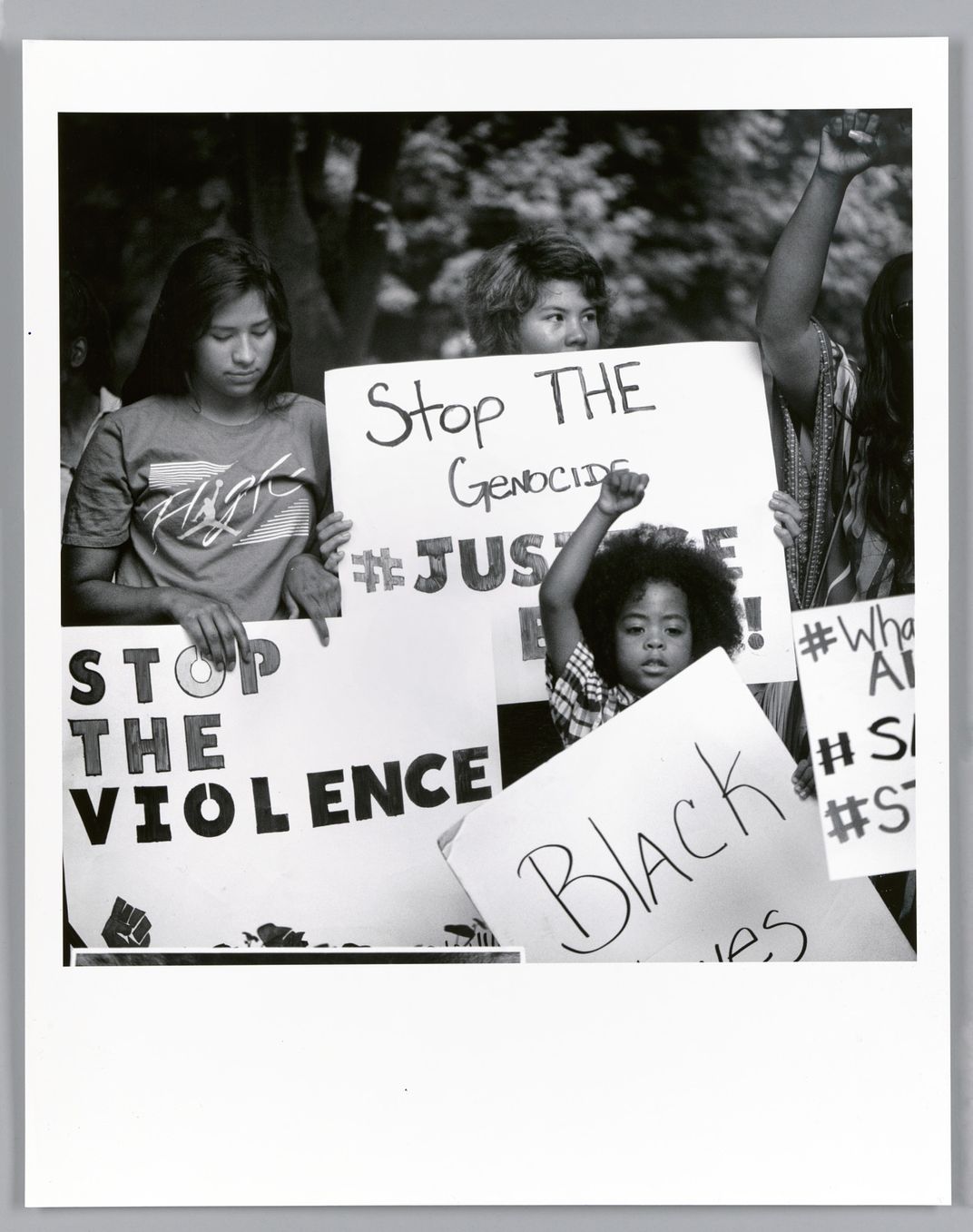

While some families have the privilege of confidently telling their child that they’re safe in times like these, this is not a reality for all children. Black children, Jewish children, and children of color may be aware of how events like the attack on the U.S. Capitol impacted their families in a different way because of how their caregivers responded to words they read, flags they saw or things they heard and watched. There are adults who feel hurt, afraid and hated right now - and it’s likely that their children know and feel some of that too.

Use this time to celebrate who your child is! Read stories about their beautiful skin. Sing songs about their heritage and culture. Remind them that they are wonderful just the way they are and they are so loved.

White adults should avoid statements that seek to make your child feel safe while ignoring that many children don't have that privilege. Statements to stay away from include, “You’re safe and don’t need to worry about this.” or “These problems won’t affect us. This is not our problem.” Instead, use words that make it clear you will keep your child safe, and that all children deserve to feel safe and loved with statements like, “It is my job to keep you safe.” or “I am here for you.”

No matter their social identities, all children need to know that their adult is going to do whatever they can to make sure they are safe and that in their home, they are important and valued. Later, age-appropriate conversations can happen that explain why or how some people are safer while others sometimes aren’t.

Look for and tell stories about the helpers.

Fred Rogers, better known as Mister Rogers, often shared his mother’s advice to, “look for the helpers,” in times of crisis. Even at the hardest moments in history, there are people making good choices and trying to help. Right now, a lot of what has been going on in the world has made both children and adults feel helpless. It can feel comforting and encouraging to know that there are people helping.

Honor children by telling them the truth and avoid making generalizations. Instead, point out individual helpers or specific ways someone made a good choice. For example, it is not true that all policemen at the Capitol that day were helpful. Some people attacking the building were officers in other towns. Instead, try this:

-

Talk about how Officer Eugene Goodman helped keep some of our leaders safe.

-

Show images of the workers who helped clean and repair the building.

-

Share stories of leaders who returned to the building to finish their important job.

Be a helper, too.

Find a safe way to be helpers as a family. Make a donation to relief efforts. Draw or write thank you notes to those who you have identified as helpers. Participate in local activism efforts. Finding ways to make a positive difference can alleviate the feeling of helplessness that accompanies difficult events and empower young people to feel their actions and responses matter and are important.

Keep the conversation going.

Start by reading part two of this series, Starting Conversations that Support Children Before Traumatic Events Happen.

-

Learn to talk about race, identity and community building with your child as a caregiver or an educator on the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Talking About Race website.

-

Discover and explore topics like bravery, emotions, fairness and justice with activity booklets and recommended resources in NMAAHC Kids: Joyful ABCs Activity Books.

-

Watch videos and read children's books about racism and activism with this MLK-inspired activities and resources guide.

-

Find books to start conversations with book lists from Social Justice Books.

-

Learn more about everyday ways to talk about important topics and events with workshops and articles from EmbraceRace.

-

Conversations with young children, who are often just developing language skills, can be challenging. Taking time to play and make art together can help children heal and process. Practice self-care with your child, while also processing current events in a concrete and age-appropriate way, with hands-on art projects from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden: Collage Flag, Story Layers, and Make a Wish.