Understanding the Power of Primary Sources through Home, Hand, and Heart

Primary sources provide learners of all ages with opportunities for deep engagement. Staff from across the Smithsonian share memorable moments in their work that have helped audiences activate their senses, make deep connections to people of the past and see their own home in new ways.

:focal(1159x960:1160x961)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Eva_Zeisel_samples_and_prototypes_2.jpg)

Primary sources refer to objects or artifacts that surround you every day. In museum practice, primary sources are documents, such as letters, financial records, recordings, images, prototypes, or objects that provide firsthand evidence of the time when they were created. If the Egyptians had documented their process and purpose for building the pyramids, we wouldn’t still be trying to figure it out centuries later—this shows the importance of primary sources.

At Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum we remind everyone that design is all around them, the same goes for primary sources. Look around your home and community—what objects hold stories or meanings small and large? Is there a family heirloom that helps you pass along an immigration story? Is there a poster or photograph commemorating an event? If you’ve shared your memories and ideas about these objects with family or friends, you are teaching with primary sources.

Primary sources are sensational!

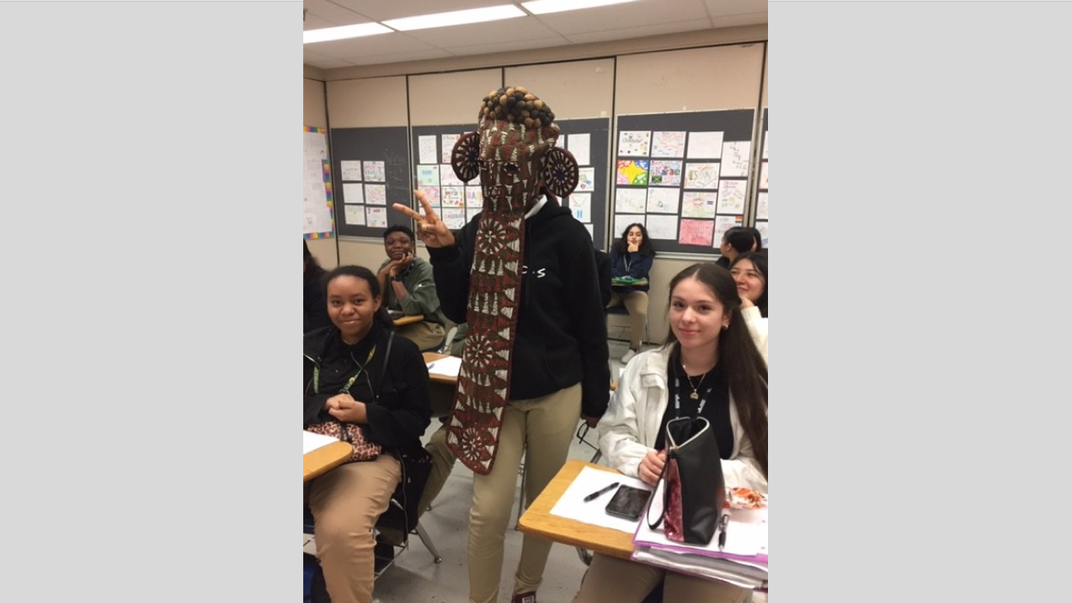

The National Museum of African Art’s (NMAfA) Education Collection, which consists of over 1,200 primary sources, is touched so often that it’s popularly called our “Hands-On Collection.” Sensory experience is key to historical art from Africa. This special collection enables visitors to touch, smell, wear, weigh, balance, play and hear primary sources, heightening their appreciation of works in the museum’s collection that they cannot touch.

We take these primary sources to schools and other sites, and we use them in the museum too. One of my treasured tour moments came about because this collection exists. It was February 20, 2020. Twenty-six students of contemporary art from Southern Virginia University visited, including a man who is visually impaired. One relies on visually rich language on such occasions, but even this only goes so far. The Hands-On Collection came out! As our guest’s hands studied several primary sources, he described the sensation, asked questions, and connected with his classmates in new ways. He marveled over the weight of a cast metal sculpture resembling Benin bronzes; he was delightfully surprised by the softness of raffia fibers cut and sewn into cloth to resemble Kuba textiles; he ran his hand across the thick paint on an Ethiopian icon, lightening his touch ever so much once aware of the work’s material and content. He played a kalimba mbira (thumb piano) and saw with his hands as he gripped a deeply carved wooden mask resembling those made by Dan artists in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Whether on the road or in-house, NMAfA’s Education Collection relies on primary sources to make the arts of Africa personally resonate with the public. It makes those primary sources we cannot touch come to life.

The power of primary sources

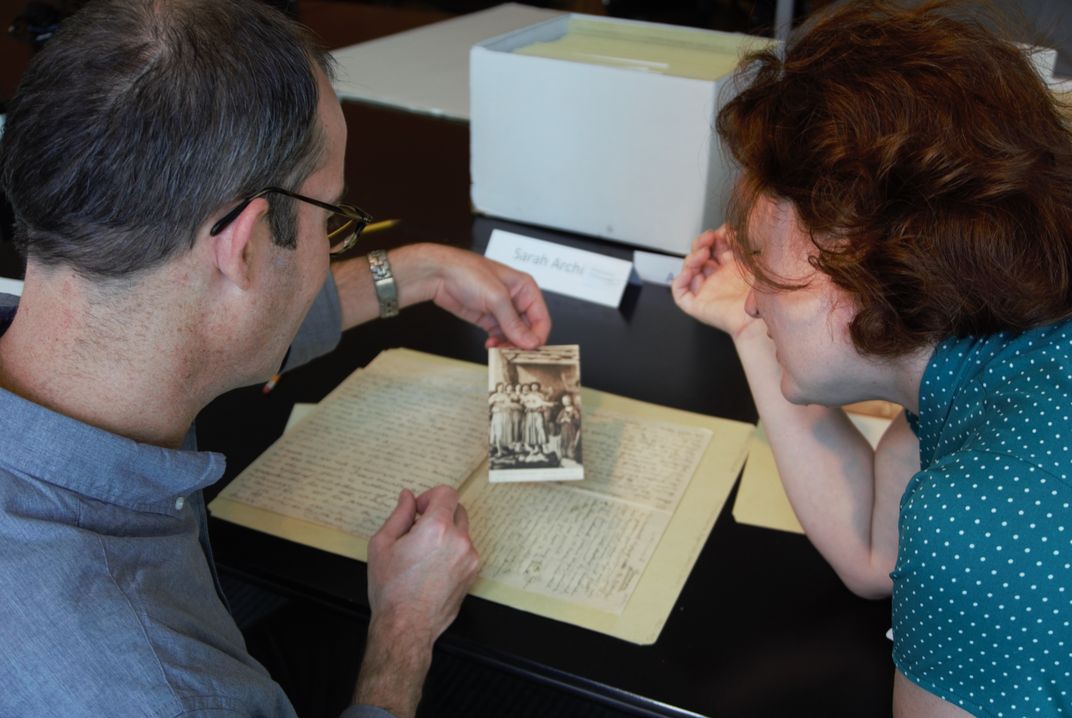

At the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, we believe in the power of primary sources to engage lifelong learners and empower students to seek their own answers, through the critical and creative reading of firsthand accounts.

Here’s one story. When our traveling exhibition, Pen to Paper: Artists' Handwritten Letters, opened at the Norton Museum of Art in Florida, the museum gathered a group of students to give gallery talks. Each picked one letter and while they all connected with “their artist” through the weight and rhythm of pen to paper, one student stood out. She chose a letter from fiber artist Lenore Tawney.

Having studied Lenore’s handwriting—as delicate as a fiber thread, and her words and images, visually and verbally poetic, the student told me that she knew Lenore, that she chose the flowered dress she was wearing because that’s what Lenore would have worn. She told the audience that Lenore saw beauty in everything and that we need to be more like Lenore and look for beauty all around us.

Through one letter, she connected with Lenore across time and space and Lenore became relevant and real to her in the present.

Things to try

Ask the ‘participant’ to first observe the object. Ask them what they think the object is or means. Allow them to create a story of their own based on clues such as the age of the materials, text or markings, the intended purpose of the object. Ensure that all senses are used—the weight of the object, texture, smell, even sound can help someone connect with a primary resource in a more meaningful way. You will find that most people can piece together some correct assumptions just from initial observations.

Next, consider offering context, such as city of origin, decade, or a person’s name. With the new information in hand allow the participant to re-visit their assumptions and build new connections. Encourage the conversation by asking the participants questions such as, ‘Do you think this letter was written for a friend or stranger and why?’ ‘Does the date make you reconsider the intent of the object's design?’ These back-and-forth questions and observations allow participants the opportunity to bring their own knowledge and experience—this is where the learning, discovery, and delight happen.

It’s your turn

Primary sources are silent until they come out from the attic, the shoebox, or a museum’s archive to find life again through shared discovery. Like color, which does not exist with the absence of light, primary sources need to have the ‘light switch’ on in order to come alive. Explore objects and artifacts in your home, your school, and your community to not only find value in the ‘stuff’ that surrounds you, but to encourage telling stories for each handwritten letter, work of art, or household object.

We would love to learn how you have explored or shared primary sources. Share your work with us on social media using the hashtag #SmithsonianEdu.