Learning About the Past to Take Care of the Future

Maps, historical photographs, and oral history excerpts are interwoven in a new online exhibition from the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum to provide a powerful case study for students to meet the people and places that shaped Barry Farm–Hillsdale in Washington, D.C., investigate what happened to the community, and discover similar stories in other communities across the country.

:focal(640x360:641x361)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3e/24/3e2488a7-7b2b-4b6d-a1b4-8bf219478b87/image1_acm.jpg)

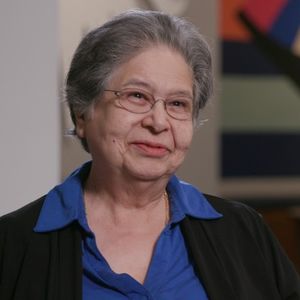

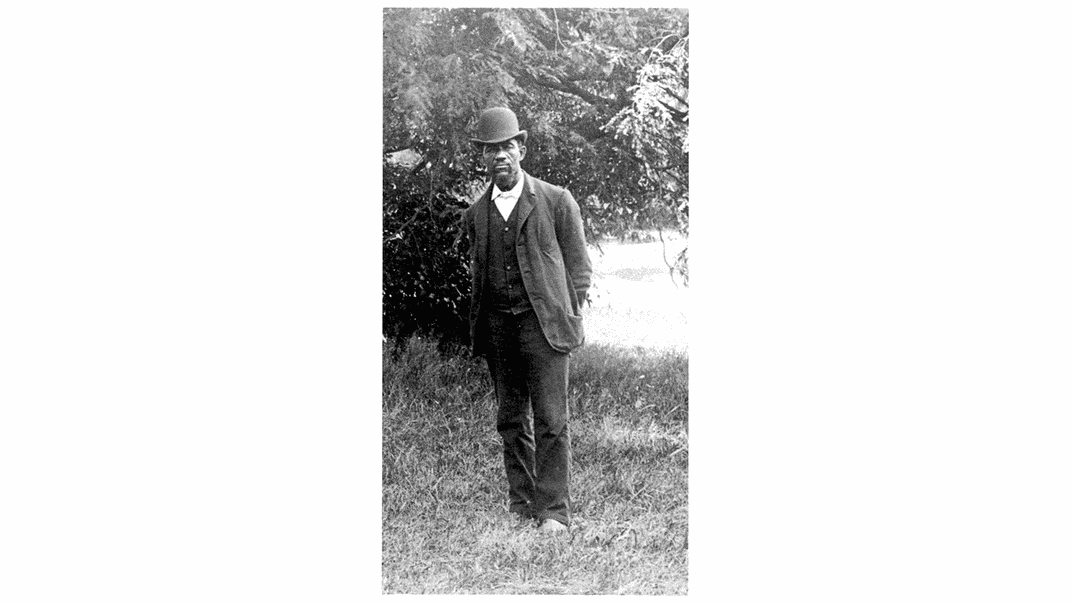

Recently, the Anacostia Community Museum launched an online exhibition, “We Shall Not Be Moved: Stories of Struggle from Barry Farm-Hillsdale,” inspired by a book I authored, Barry Farm-Hillsdale in Anacostia: A Historic African American Community. Through a series of maps, historical photographs, and oral history excerpts, visitors can investigate what happened to this longstanding neighborhood that formed with assistance from the Freedmen’s Bureau right after the Civil War in 1867. This once-thriving African American community in Washington, D.C., had essentially disappeared by the 1970s, just one hundred years later.

This highly interactive exhibit fits the teaching requirements of the National Curriculum Standards for Social Studies, Themes of Social Studies, Time, Continuity, and Change, which states that “Social studies programs should include experiences that provide for the study of the past and its legacy.” Teachers looking for ways to have their students better understand the past and its effect on the present will find this exhibition a helpful online interactive exercise and case study for further discussion.

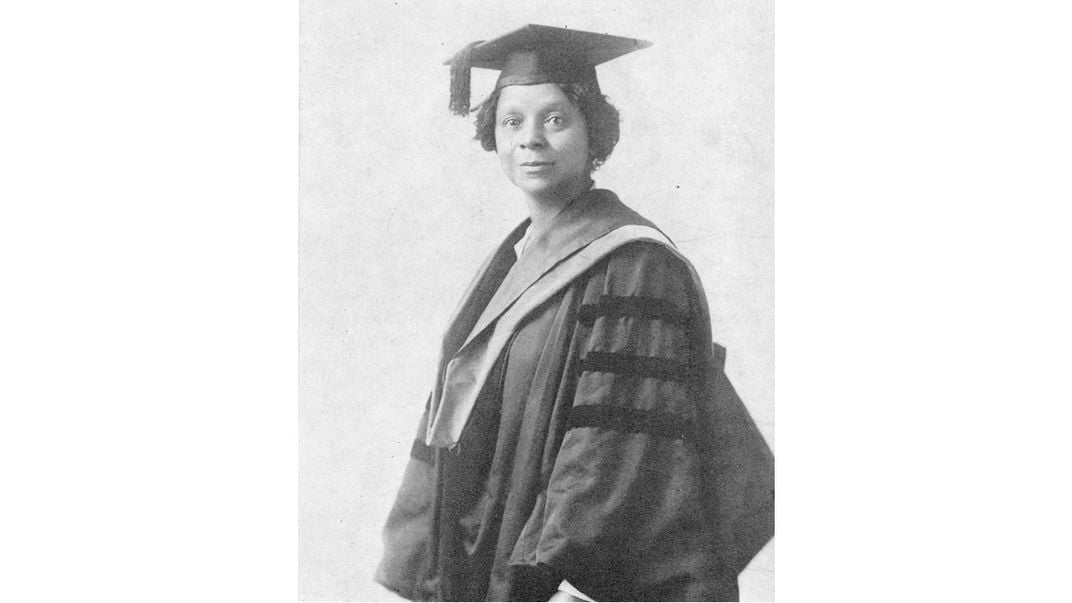

In the exhibition's first section, “Explore the Neighborhood,” visitors will be able to delve into the history of the places and people that created the community: the schools; the teachers; the leaders, both male and female; the businesses; the historical buildings; the entertainment venues, etc. In the next part of the exhibition, “Community Activism,” visitors can learn about the rich history of organizing in which residents valiantly confronted the challenges they faced over the decades.

Visitors to the exhibition will learn that in 1877, male and female residents signed a petition demanding women’s right to vote. This petition was part of a larger one that included 10,000 signatures and was delivered to Congress by Susan B. Anthony's National Woman Suffrage Association later that year.

In the 1940s, the community fought the threat of redevelopment when the National Capital Park and Planning Commission sought to raze the community and rebuild it in conformity with its own plans. The fight to save Barry Farm-Hillsdale, led by the Barry Farm Civic Association, culminated with Congress passing a law in 1949 forbidding the neighborhood's redevelopment.

Visitors to the exhibition will learn about the pivotal role played by the youth of Barry Farm-Hillsdale in the integration of the whites-only Anacostia swimming pool in 1949. Their efforts led to the eventual desegregation of all swimming pools in Washington, D.C. In the 1960s, the community's youth organized under the name Rebels with a Cause to obtain improvements in the community's recreation facilities and opportunities for quality jobs and education. Eventually, the Rebels were the model for a citywide anti-poverty and anti-delinquency program that helped thousands of young people.

Also in the 1960s, the women of Barry Farm Dwellings organized themselves as the Band of Angels. These women were self-described “welfare mothers” who were tired of the insufficient and discriminatory welfare system and of living in terrible physical conditions at the Dwellings. Within months of their founding, the Band of Angels articulated the issues that later became the centerpiece of countrywide welfare activism. Etta Mae Horn, one of the early organizers of the Band of Angels, became a national advocate for the rights of welfare recipients.

In the 1950s, the fight to desegregate the schools in Washington, D.C., was centered in Barry Farm-Hillsdale. It culminated with the 1954 desegregation of schools when the Supreme Court handed down the Bolling v. Sharpe decision, alongside Brown v. Board of Education. Recently, residents of the Barry Farm Dwellings have fought to preserve their public housing community from redevelopment, citing its role in historic Barry Farm-Hillsdale. They were successful in getting five of its original buildings designated for preservation.

In a third section of the exhibition, “Investigate,” students will learn how the community was negatively impacted over the course of its existence by government seizure of land, known as “eminent domain.” Eminent domain is the legal right of the government to take private property for public use, as long as it provides “fair” compensation in doing so. Visitors to the exhibition will understand the how this this legal concept has played out, including in communities today. In the case of Barry Farm-Hillsdale, the government designated large swaths of land to be taken through eminent domain and paid property owners an amount that most deemed unjust.

The impact of the community's uncontrolled growth in the 1940s and the more recent push for redevelopment and gentrification are also explored in the “Investigate” section. The use of “before and after” photographs and maps clearly show the physical impact of the loss of land in Barry Farm-Hillsdale.

Another important aspect of the exhibition is the extensive use of excerpts from oral history interviews with community members who lived through the events being depicted or heard the stories from their elders who had lived them firsthand. These voices from the past vividly describe how historical events impacted individuals' lives.

The last part of the “Investigate” section, titled “Stories of Struggle Across the U.S.,” reveals that what happened to Barry Farm-Hillsdale was far from uncommon. Visitors can explore the stories of eleven African American communities throughout the United States that have been similarly destroyed or are fighting for survival today. Visitors are asked to compare what happened to Barry Farm-Hillsdale with what has been happening in these other communities and to analyze the causes and consequences.

The very last section of the exhibition, “What do you think?,” invites visitors to vote on what they think was the most significant turning point in the history of Barry Farm-Hillsdale. They will also be asked to share their stories and answer two essential questions: “Do you think people should have the right to remain in their neighborhood?” and “Who should have the right to decide?” As key elements of teaching and learning in social studies, these types of culminating questions allow students to use multiple sources to build and defend their interpretations of the past, and to draw on their knowledge of history to make informed decisions.

Throughout, this exhibition emphasizes a valuable message to its visitors: that we need to understand the past and act in the present to protect the future of our communities.