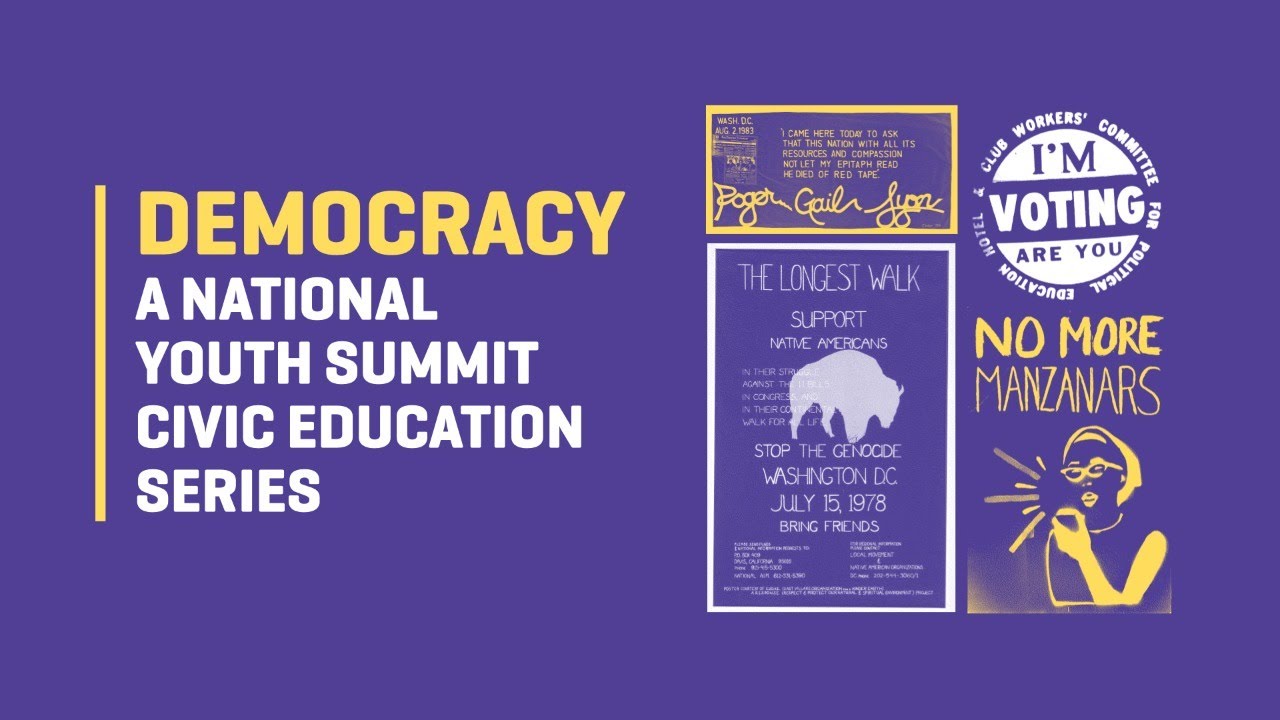

To Reimagine the Future, Start by Expanding the Stories of Our Past

Looking back at beloved children’s stories and historical narratives taught in the classroom, two educators ask us to consider whose perspectives were centered. Through ongoing National Youth Summit programming, historical case studies provide an opportunity for students to expand their thinking about stories of our past.

:focal(640x363:641x364)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6d/bb/6dbb4324-f6e7-4ac2-b832-8183e90f3298/nys.png)

Each year, the National Museum of American History (NMAH) brings together young people for a conversation on a topic of their choosing, a National Youth Summit (NYS). We meet with young people and ask them what they are interested in learning about and discussing together. Recent summits have centered Woman Suffrage, Teen Resistance to Racism, and Gender Equity. This year, we are discussing Democracy. Our driving question is, “How do the stories we tell about the past shape our democracy?” In particular, we are interested in how these stories, the perspectives they hold, and people they center impact how we imagine what democracy is and can be. Diverse and inclusive protagonists, authors, and narratives are vital to cultivating imagination, creativity, and empathy. As educators, we should be creating learning environments that provide our students windows and mirrors: points of entry into experiences different from their own, as well as opportunities to reflect on their lives and histories in relationship with others. The alternative, one narrative and perspective, is myopic, even dangerous. Turning to a current example from popular culture illustrates what happens when a singular point of view is perpetuated.

“Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.”

-Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The "Danger of a Single Story" in Storytelling Today

In 2010, Walt Disney Pictures began shifting how it used its intellectual property. Up to that point, the company’s strategy mostly consisted of creating demand for its classic films by releasing them for limited windows of time, then “putting them back in the vault.” Children everywhere badgered parents to buy film x because if they did not, it would no longer be available to them for many years. This all shifted with the release of a new live-action Alice in Wonderland directed by Tim Burton and starring Burton regulars Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter. The cast was filled out by Anne Hathaway, Michael Sheen, and the late Alan Rickman among others. Alice became the second highest grossing film that year, beaten only by another Disney property, Toy Story 3. New film technology combined with advancing and continuously improving computer generated imagery (CGI) opened new avenues for content repurposing. If Disney could re-make one of its most visually rich stories in Alice, which other narrative from its vault could it reimagine with live actors in CGI landscapes?

Disney had quite a few hits, some misses, some lukewarm receptions. Maleficent (2014) whose plot recast the villain in Sleeping Beauty as protagonist was generally well regarded. It was released in a cultural moment when several popular narratives cast antiheroes as protagonists, think Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and Wolverine. For the most part, Dumbo (2019) was panned. It did not perform at the box office, nor did critics enjoy it. Beauty and the Beast (2017) fell somewhere in the middle. It did well at the box office; critics and audiences generally enjoyed it. For many, this was due to the fact that casting decisions for the live human version of a fictive, and in large part, inanimate universe, matched the animated version. In other words, expectations of who audiences imagined as Belle were met by the casting of Emma Watson, fresh off Harry Potter fame. Last month, the expectations and imaginative capacities of several moviegoers were pushed past their limits.

Just a few weeks ago, the release of the trailer for the live action The Little Mermaid produced immediate opinions and reactions. For many young Black girls, the sight and sound of Halle Bailey singing the well-known refrain “wish I could be part of that world” brought joy - “She’s brown like me!” The diverse cast includes several people of color, people born outside the U.S., and white actors including Daveed Diggs, Akwafina, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Javier Bardem, Noma Dumezweni, and Melissa McCarthy. Unfortunately, other parts of the internet responded to Bailey’s casting with thinly or overtly racist reactions that culminated with the trending hashtag #NotMyAriel and an internet user photoshopping the trailer with a white CGI Ariel. The lack of people of color in mainstream fantasy, science fiction, and speculative fiction is well-documented and led to Alicia Wormsley coining the phrase that became a movement, “There are Black people in the future.” At issue here is not whether Ariel, a hobbit, or the seat of House Velaryon are people of color in worlds that do not exist. The issue is the difficulty some folks have in imagining that these could be people of color. This fallout provides an important reminder of what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls “the danger of a single story.”

The manufactured controversy created by a Black actress being cast in a fantasy story is simply the most recent example of, at best, the imaginative limits of some moviegoers. At worst, their racist biases. In her TED Talk, Ngozi shares the power stories had in her early days as writer in Nigeria:

All my characters were white and blue-eyed, they played in the snow, they ate apples, and they talked a lot about the weather, how lovely it was that the sun had come out. Now, this despite the fact that I lived in Nigeria. I had never been outside Nigeria. We didn't have snow, we ate mangoes, and we never talked about the weather.

Exposed to only one point of reference, Ngozi had difficulty imagining a non-white cast of characters – that is the danger of the single story, a single perspective – our imaginations become stunted. The inverse is true as well. In the aftermath of The Little Mermaid trailer, television host Amber Ruffin dedicated one of her “How Did We Get Here?” segments to explaining how and why some white moviegoers react so negatively to people of color being cast in roles. The empathy gap, the difficulty people have relating to someone who does not look like them, makes it difficult for white audiences to relate to and subsequently want to see stories that center Black people. As Ruffin explains, the preponderance of stories that center white characters and voices is the result of decision makers who are white and want to see themselves in the stories presented on a screen. Unfortunately, this creates a reinforcing and closed feedback loop. A solution then is to both have more diverse stories and storytellers. Diversity and inclusion benefit everyone by helping us see ourselves, see each other, and broaden our imaginative capacities. As much as closing the empathy gap matters in our popular culture, it matters in our classrooms even more. It is after all where our young people live 30-40 hours a week listening, reading, viewing, and analyzing stories.

Exploring Multiple Perspectives with Students in Storytelling about the Past

I will tell you something about stories

[he said]

They aren’t just entertainment.

Don’t be fooled.

They are all we have, you see,

all we have to fight off

illness and death.

You don’t have anything

if you don’t have the stories.

….So they try to destroy the stories

let the stories be confused or forgotten.

They would like that

They would be happy

Because we would be defenseless then.

He rubbed his belly.

I keep them here

[he said]

Here, put your hand on it

See, it is moving.

There is life here

for the people.

-Leslie Marmon Silko, Ceremony

Leading organizations for social studies classroom curricula require diverse and inclusive perspectives and stories because of the emphasis they have on relationships between peoples. The National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS), the NCSS College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework, UCLA Public History Initiative standards, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), National Council on History Education (NCHE), and Educating for American Democracy (EAD) all center encounter, meeting, coming together, changing perspectives, and/or diversity throughout their materials. In other words, social studies instruction requires diverse and inclusive stories and storytellers for the sake of accuracy and scholarship. However, it is also helpful in helping each student both see themselves and learn about each other. It is by doing this that we can open up imaginative possibilities for what the U.S. could be and become. We read and write ourselves out of the danger single story by doing what Laguna writer Leslie Marmon Silko whispers in the opening to Ceremony: keep the myriad stories we have safe to keep ourselves alive, creative, and open to multiple futures. On November 15th, NMAH shared the story of “The Longest Walk,” an important moment in Native American history that served as a reminder of promises broken and pointed the way forward for a more just future.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1e/1a/1e1a3076-9a9a-4b1e-9214-9ef54575366e/nmai_drum_amplifier_and_accessories.jpg)

We invite you to join us to learn with us, discuss with us, and imagine with us. In January, we will continue our series by focusing on the AIDS quilt made during the 1980s and asking the question, “How do understandings of democracy change when more perspectives are added?” In March, we will center the “No More Manzanars” movement and ask, “What tools are available to shift, expand, and reimagine the story of democracy in the U.S.?” We will conclude our series with a teach-in event in April. Please visit NYS Democracy for updates.