SMITHSONIAN ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH CENTER

New Study Reveals Large Holes In America’s Ocean Protection. Here’s How We Can Fix Them.

Many governments are leaning on marine protected areas to fight biodiversity loss. But in America, ocean protections are uneven and often weak, leading scientists to call for new strategies.

:focal(512x341:513x342)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/96/35/96353f41-6c3c-4c85-ad2a-01bd0f1192be/coral_reef_at_palmyra_atoll_credit_usfws.jpg)

Thousands of marine species, and many vital habitats, have little to no coverage in America’s marine protected areas, according to a new study co-led by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. With biodiversity loss accelerating, many governments have been leaning on protected areas to preserve important species and ecosystems. But surprisingly, much of this effort is missing a key ingredient–information on the species they are aiming to protect. This means a large fraction of those protected areas may be falling short of their mission, if not designed with biodiversity specifically in mind.

Officially, 26% of U.S. waters fall under the shelter of a marine protected area, or MPA. That’s a respectable figure, and very close to the “30% by 2030” conservation targets for land and water embraced by the global community and the Biden administration.

However, the figure masks some troubling inequities. The vast majority of MPAs—a full 96%—are in the central Pacific. Other regions, especially Alaska and the Caribbean, have been left behind. Furthermore, most MPAs in the U.S. are only partially protected. A mere 3% are considered “fully protected areas,” where fishing and other destructive activities are completely prohibited.

“Few regions meet criteria to protect biodiversity in a way that would ensure health and resilience in marine ecosystems as a whole,” said Emmett Duffy, a co-author and senior scientist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC).

The Missing Pieces

The study, published in the journal One Earth, represented the first nationwide attempt to quantify biodiversity inside and outside all the country’s marine protected areas. The authors sought to answer one crucial question: Are the United States’ protected areas capturing the full diversity of species and habitats that call these waters home?

“It is especially important that we understand what biodiversity we are actually conserving in U.S. waters,” said Sarah Gignoux-Wolfsohn, lead author and a former SERC postdoc now at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. “This paper can serve as a baseline assessment of current protections and provides a framework for the future.”

Of the nearly 30,000 species known to live in U.S. ocean waters, the study estimates only three-fourths appear in any marine protected area at all. The authors reached this figure by looking at all the records for species inside and outside protected areas and correcting for different survey methods.

However, the scientists suspect this overestimates the real number of species protected. Since marine protected areas are popular study sites, far more data exists for species inside them than outside. This makes it easy for species found only outside protected waters to escape notice. The study also counted a species as “present” in a protected area even if only one specimen appeared—which hardly makes for a viable population.

Quality Over Quantity

The species numbers tell only part of the story. The authors also took a holistic look at how each region of the U.S. is protecting the species and habitats in its waters.

“Protection of marine life requires a network of protected areas that are more than the sum of their parts,” said Shannon Colbert of the National Marine Sanctuaries Foundation, which helped fund the study.

The U.S has 24 marine “ecoregions” that cover its diverse coasts and islands. Most ecoregions contain multiple individual protected areas. To have the best shot at conserving vital species and habitats, each region’s network of protected areas needs to pass five tests, defined by the Convention on Biological Diversity:

- Important areas—Does the network include critical spots that species rely on for feeding, spawning or other major life activities?

- Representativity—Does it include the full range of a region’s biodiversity?

- Connectivity—Can species readily move between protected areas in the network?

- Replication—Does it have critical redundancy? If one protected area in a region fails, can similar ones fill in the gaps?

- Viability and Adequacy—Are protected areas large and strong enough that the network can sustain its ecosystem into the future?

None of the nation’s 24 ecoregions passed all five tests, though most passed some. Large marine mammals, like whales and dolphins, were of special concern. Less than 10% of the important areas they rely on received official protection. More than one-fourth of the United States’ ecoregions do not even formally designate important areas for marine mammals. Seabirds fared better, with nearly 60% of their important areas protected.

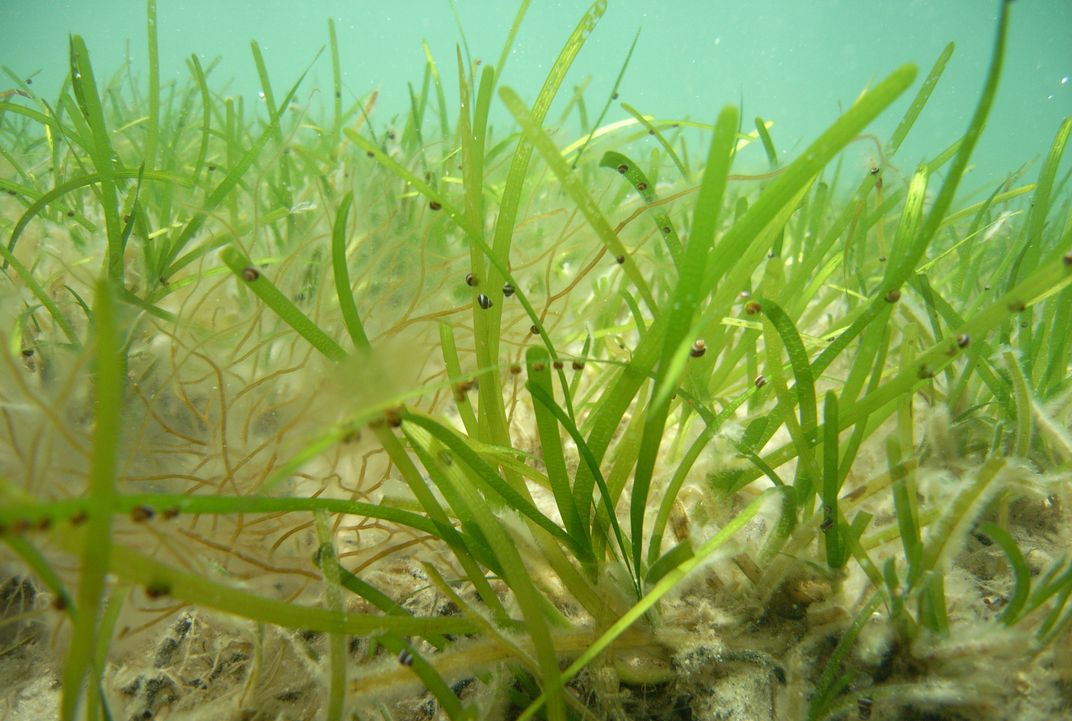

On average, coral reefs—Earth’s most famous biodiversity hotspots—are better protected than other habitats. However, this conclusion is misleading: It reflects the enormous protected areas in the Pacific Islands. Corals in the Caribbean are severely underrepresented, and deep, cold-water corals have almost no protection at all. But other vital habitats, like mangroves and seagrasses, received comparatively good coverage.

A New Blueprint: What Counts As Protection?

The study offers a wave of suggestions for improving marine protection. “Stepping-stone MPAs” could create vital connections to help species move between protected zones. The study also calls for protecting more critical areas for marine mammals and birds, and for prioritizing coverage of deep-water corals, which are key habitats for many fishes.

Perhaps one of the most powerful opportunities involves embracing some less traditional forms of protection.

Community-led and tribal-led efforts can offer real conservation benefits, even if their goals are ostensibly different than traditional MPAs. These fall under the category of OECMs, or “Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures.” Examples include sacred sites, shipwrecks, locally managed fishing zones closed seasonally or zones open only for small-scale or indigenous fishers.

While the protections of OECMS may not be as strong as formal MPAs, they can be longer lasting and better enforced thanks to community buy-in. Having them in place can also improve connectivity between official MPAs.

Right now, the U.S. does not have a formal designation for OECMS. However, according to the authors, such recognition could improve the country’s ocean conservation efforts.

Finally, the authors emphasized that protection is a continuing process, requiring regular, long-term monitoring of key species and habitats. This can ensure marine protected areas are still doing what we need them to in a rapidly changing world. The framework the team developed in this study offers a starting point.

“Our work provides the basis for consistent, systematic characterization of biodiversity at a national scale,” said co-author Daniel Dunn of the University of Queensland, “enabling us to understand how species and habitats are both changing over time and responding to management interventions.”

This study was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation and the Lenfest Ocean Program. The article, “New framework reveals gaps in US ocean biodiversity protection,” is available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.12.014. A detailed, plain-language fact sheet about the new biodiversity framework is available on the Lenfest Ocean Program website here.