OFFICE OF ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND INTERNSHIPS

Help, a Tapir is Trying to Eat My Leaves! A Month of Plant Ecophysiology in Yasuní

It’s hard being a plant leaf - being eaten is a major risk. In tropical forests, ~10-15% (>70% in some species) of leaf area can be lost via herbivory (Cardenas et al., 2014; Coley & Barone, 1996). Plants may counteract herbivory via resistance, where chemical or mechanical defenses are used to deter herbivores, or resilience, where the effect of unavoidable damage is mitigated (Kursar & Coley, 1996).

It’s hard being a plant leaf - being eaten is a major risk. In tropical forests, ~10-15% (>70% in some species) of leaf area can be lost via herbivory (Cardenas et al., 2014; Coley & Barone, 1996). Plants may counteract herbivory via resistance, where chemical or mechanical defenses are used to deter herbivores, or resilience, where the effect of unavoidable damage is mitigated (Kursar & Coley, 1996). Each strategy predicts that certain leaf traits should be correlated with herbivory, but few consistent empirical relationships have been found (e.g., with leaf thickness, shear resistance, leaf age). Thus broad-scale predictions of herbivory response and impacts on forest productivity are challenging. Venation network traits may predict herbivory response, which vary widely across species. Networks with more looping (reticulate veins) have redundant flow pathways, which could increase damage resistance and/or improve resilience by limiting damage spread. However, linkages of looping with herbivory have not been explored.

Thus, we (Dr. Luiza Aparecido and Dr. Benjamin Blonder, Arizona State University-ASU*) packed our botanical plant presses (five of them!) and our portable photosynthesis machine (LI6800, Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE) and headed to the Ecuadorian Amazon to investigate whether vein looping does indeed mitigate the effects on leaf gas exchange of a damaged vein network, in this case a simulated herbivory attack. Data collection was made possible due to a 2018 CTFS-ForestGEO research award and via collaboration with Yasuní principal investigator and Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (PUCE) professor, Dr. Renato Valencia, and PUCE collaborator Dr. Rafael Cárdenas.

The journey to Estación Científica Yasuní was not an easy feat. International travelling aside, the route from Quito included a 10-h bus ride, 1.5-h truck ride, 10-min canoe trip across the Rio Napo (Figure 1), and 2-h van ride to the station. However, all is worth it after arrival, secluded with tropical nature, other fellow field ecologists, and members of the local Huaorani Indigenous communities.

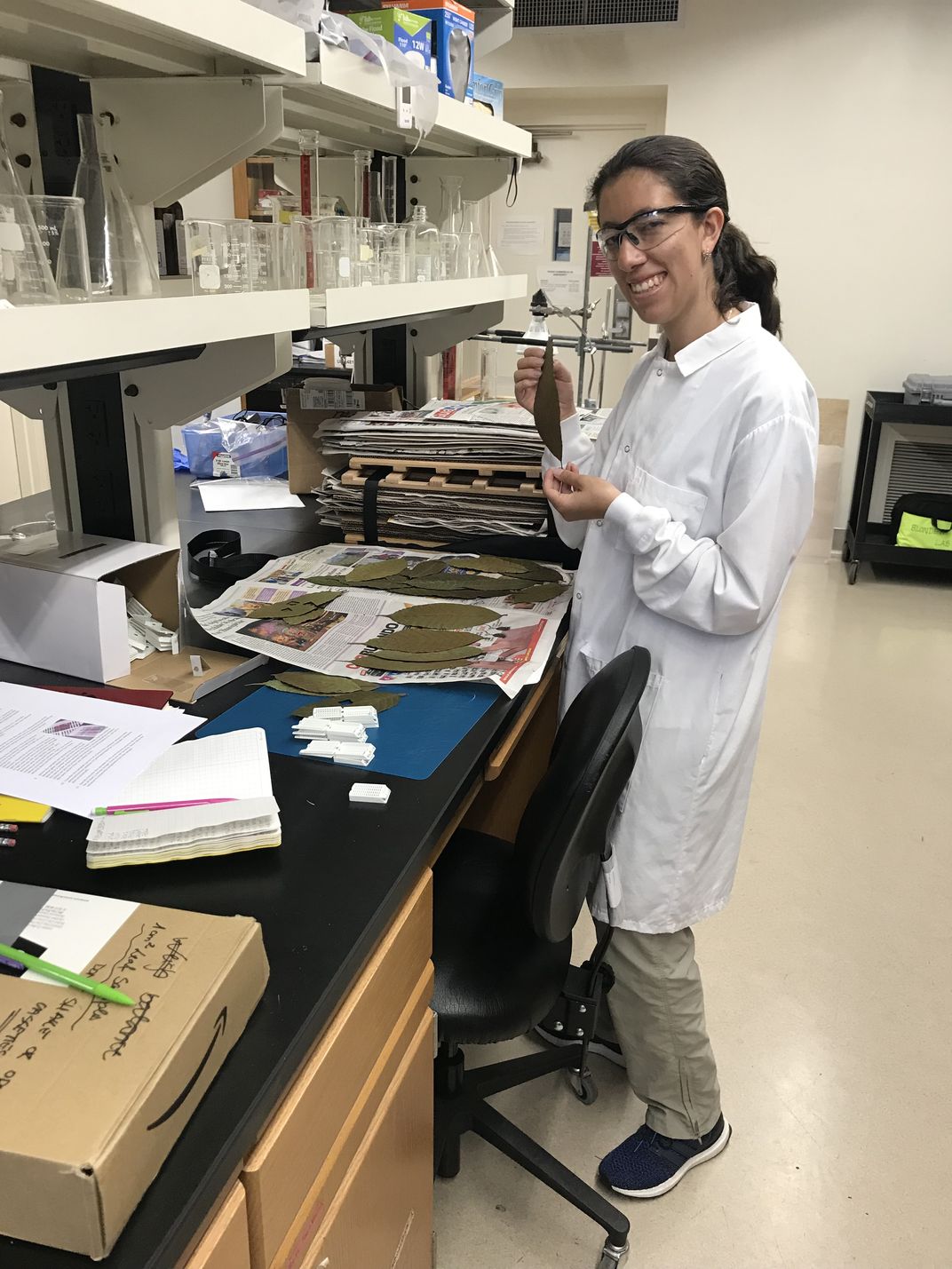

Our goal was to collect branch samples of a wide range of tree species (32 total) within the Smithsonian/ForestGEO 50-ha plot within Yasuní National Park (Ecuador). Samples were retrieved during the daytime for gas exchange measurements. Branches were placed in buckets filled with water (to maintain sample viability), and also treated to simulate an herbivory attack, by cutting major and minor veins (Figure 2). After gas exchange measurements were taken from treated and untreated leaves (Figure 3), they were scanned and dried out in an oven to be subsequently stored for future lab analyses at Arizona State University. Sample collection and leaf pressing were meticulously done by undergraduate senior Emily Guevara Heredia (PUCE), and field botanist Pablo Alviar (Yasuni) (Figure 4).

Even though we were able to collect samples for all 32 species, not all samples were viable for gas exchange. The first limitation was time. Taking measurements of various branches from various species replicates was highly intensive. Some species did not acclimate or stabilize its metabolism while in a bucket of water, so there were numerous branch samples and time lost. In the end, we were able to collect high quality gas exchange data from 20 species. Other challenges encountered in the field included: species that were hard to find (once again, time running out); dodging storms and floods; branches that were too old or too herbivorized for measurements; insects affecting the machine mechanics; branches with such hard wood that the pruner did not work; thousands of leaves to scan and keep track; and many other tropical creature encounters.

But nothing tops our interactions with a local tapir (named Omaca) who often visited the station, and for more than a few days tried to eat our samples (Figure 5). We had not planned for any ‘real’ herbivory in the study - only simulated damage! Fortunately she was friendly enough, and placated with other branches and fruits from the station grounds. But, overall, measuring gas exchange in such exuberant forest alongside interesting people made the whole trip a wonderful experience.

After 20 days of gas exchange measurements and data collection, we headed back to Quito and later Phoenix, Arizona (USA) to proceed with our leaf venation analyses. This process involves chemically clearing leaves, in which non-lignified tissue is dissolved, leaving only the vein structures of the leaf. Our PUCE bachelors’ thesis student Emily was an essential part of this process, in which she not only brought all the dried leaf samples from Ecuador but also was able to stay with our team in the United States for several months, leading efforts to complete at least one whole-leaf and one microscope slide of the vein architecture sample from each species (Figure 6). Believe me, this was no easy task!

Currently, we are working hard on retrieving the leaf venation parameters from these samples (Figure 7), in which looping and vein density are our main parameters to be correlated to gas exchange dynamics after vein damage. Preliminary results from gas exchange measurements indicate a large variability of responses among species. Some species decreased gas exchange rates when both major and minor veins were damaged; while other species decreased one over the other, or increased (interestingly!), or no effect at all from damage. We are hoping that vein parameters and other leaf traits (such as leaf mass per area) will help us explain these highly variable responses. This study will not only excel in the field of leaf ecophysiology, but will most certainly strengthen our understanding on how various defense mechanisms and resource allocation strategies can balance the effect of stressors within highly biodiverse ecosystems.

*Benjamin Blonder’s lab has now moved to the University of California, Berkeley.

REFERENCES

Cárdenas RE, Valencia R, Kraft NJB, Argoti A, & Dangles O (2014) Plant traits predict inter- and intraspecific variation in susceptibility to herbivory in a hyperdiverse Neotropical rain forest tree community. Journal of Ecology 102(4):939-952.

Coley PD & Barone J (1996) Herbivory and plant defenses in tropical forests. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 27(1):305-335.

Kursar TA & Coley PD (2003) Convergence in defense syndromes of young leaves in tropical rainforests. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 31(8):929- 949.