OFFICE OF ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND INTERNSHIPS

A Painted Homage to A Political Giant: G.P.A. Healy’s Posthumous Portrait of President Lincoln

U.S. artist George Peter Alexander Healy’s (1813 – 1894) 1887 portrait of President Abraham Lincoln (1809 – 1865) was the culmination of a career devoted to presidential portraiture. The image, conceived years after the sitter passed away, helps us understand the practice of nineteenth-century portraiture as much as the challenge of posthumous portrait painting. The result of Healy’s work is an iconic image of a political giant that still resonates today.

U.S. artist George Peter Alexander Healy’s (1813 – 1894) 1887 portrait of President Abraham Lincoln (1809 – 1865) was the culmination of a career devoted to presidential portraiture. The image, conceived years after the sitter passed away, helps us understand the practice of nineteenth-century portraiture as much as the challenge of posthumous portrait painting. The result of Healy’s work is an iconic image of a political giant that still resonates today.

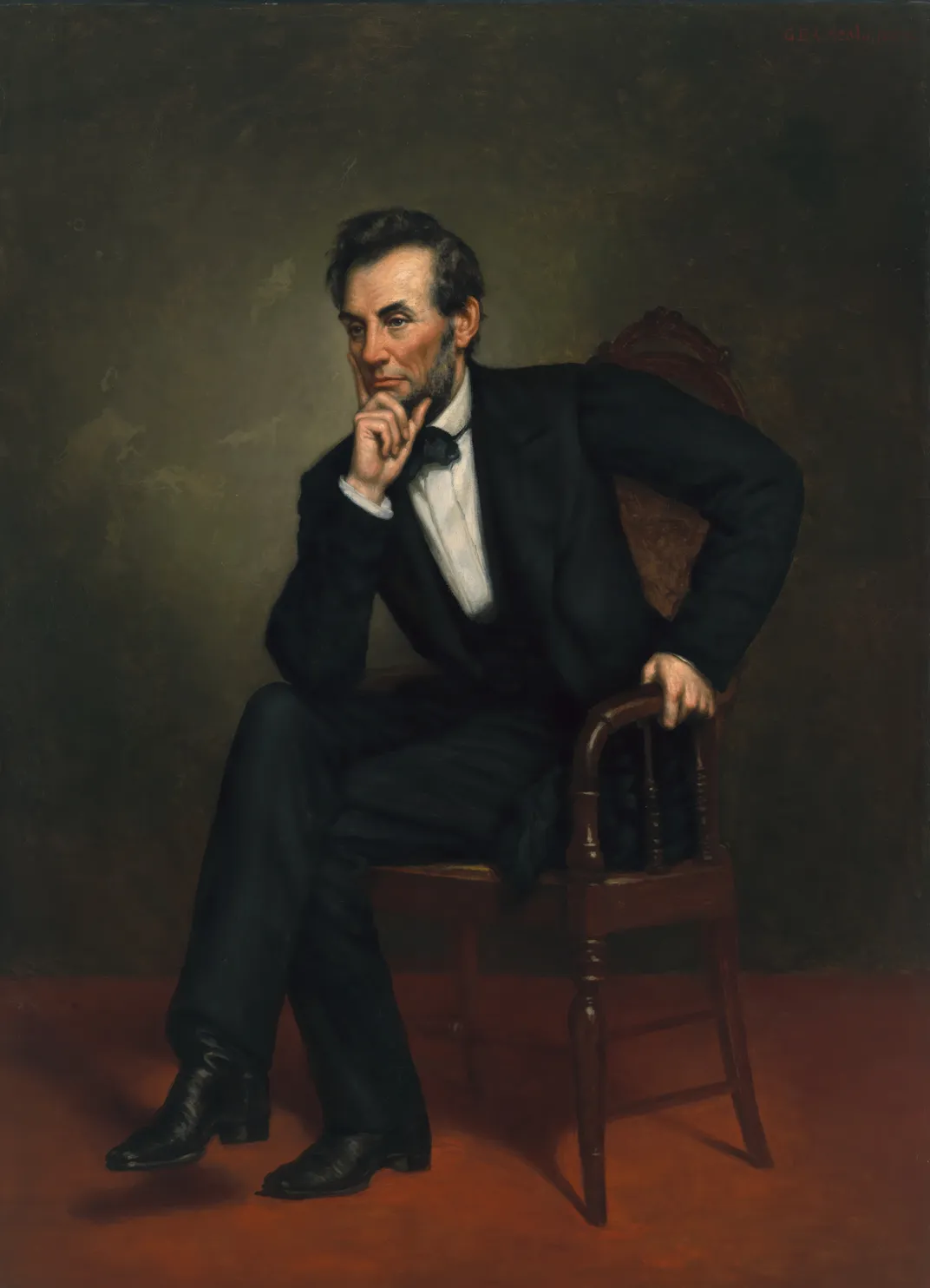

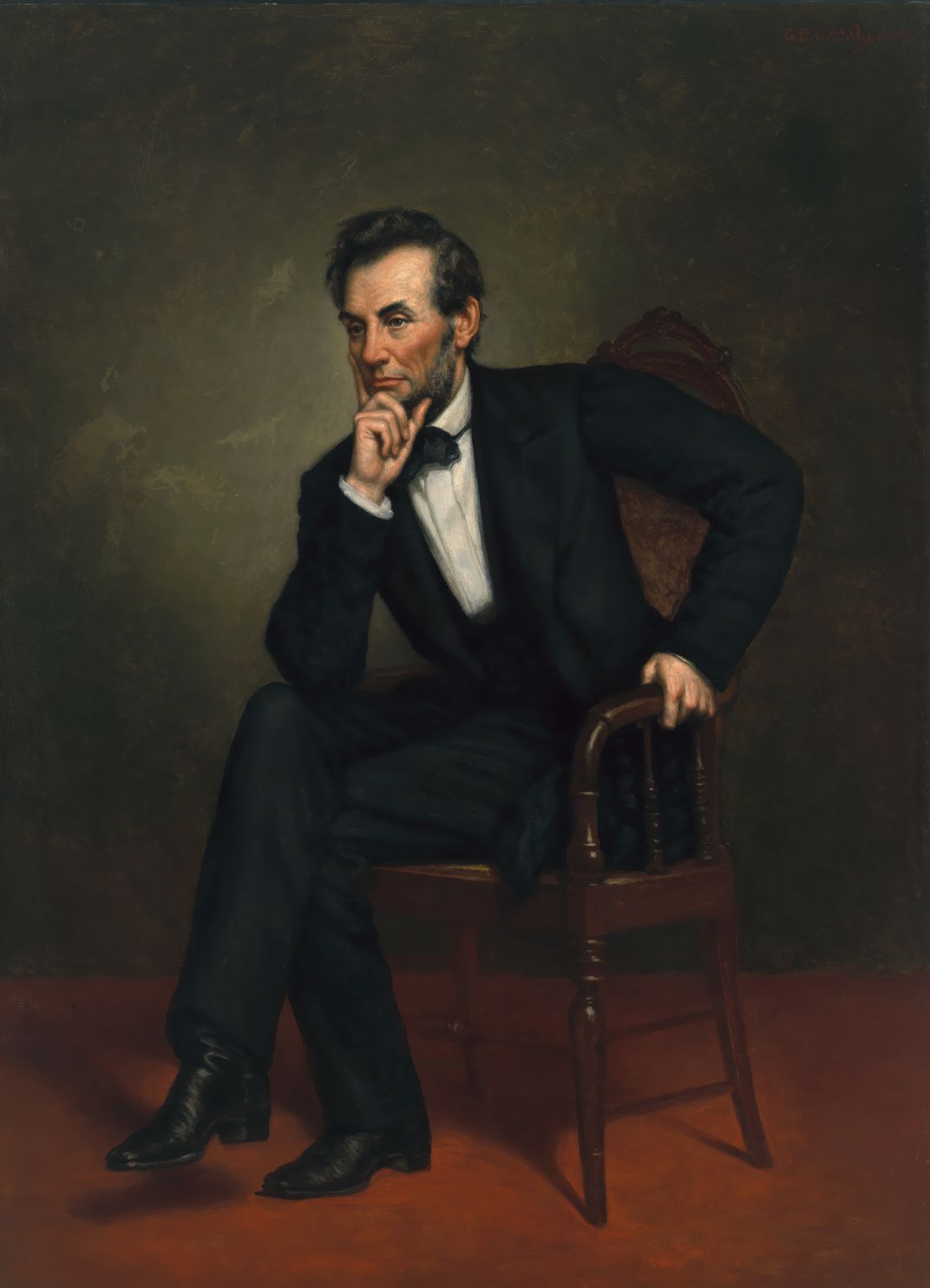

The portrait depicts Lincoln sitting down in a plain chair against an abstract background. Lincoln is wearing his office suit, with his characteristic bow tied in a diamond point. The skirt of his black coat is caught by the arm of the chair. The chair is the type of plain spindle chair used in Abraham Lincoln's Presidential Rail Car, which Lincoln never used in life. Ironically, this was the railroad vehicle that carried his deceased body from Washington D.C. back to his home in Springfield, Illinois. The simplicity of the chair’s design and the trapped skirt suggest an atmosphere of informality and carelessness. Healy depicts the sitter in a pensive gesture, holding his chin with the hand, in a position he allegedly used often to think. The bodily posture presents an uncomfortable combination of leg crossing with a bent arm. This appears an artistic license to bring the sitter’s torso forward towards the viewer; the curved arm echoes the curve of the chair’s crest rail and arm, emphasizing arched lines to provide elegance to the composition.

Healy’s “seated Lincoln” was a posthumous portrait, meaning that the sitter had died when the portrait was painted. When Healy initially composed the figure in 1867 in his Chicago studio, he invited Lincoln’s friend Leonard Swett to pose as Lincoln. Lincoln’s son Robert Todd, who also lived in Chicago, gave the artist advice on how to make the painted image resemble his deceased father. Healy was a fastidious artist who requested a minimum of six sitting sessions of two hours each, ideally in his own studio, in order to create a portrait. This posthumous work likely required several sittings to get the bodily posture and the clothing right.

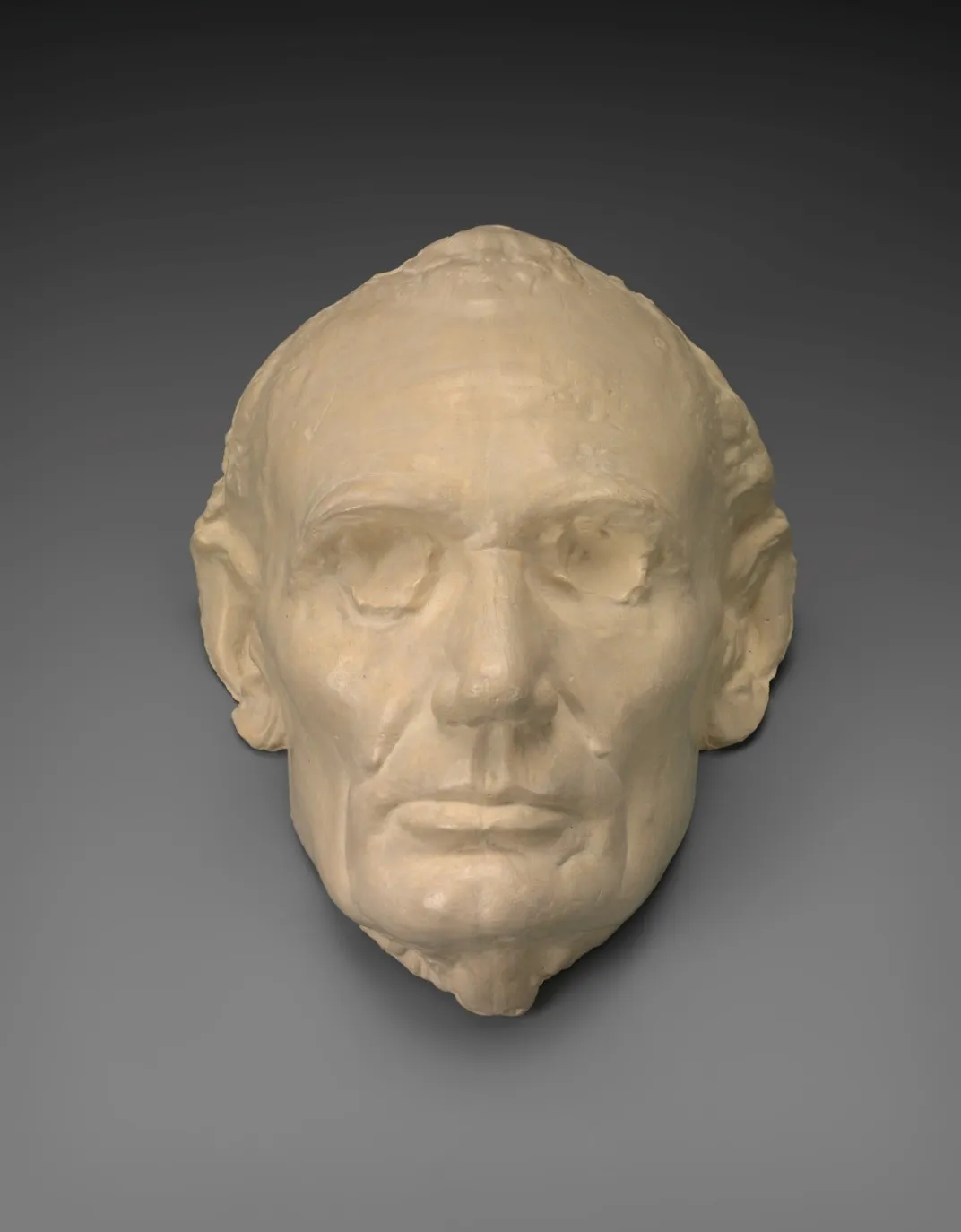

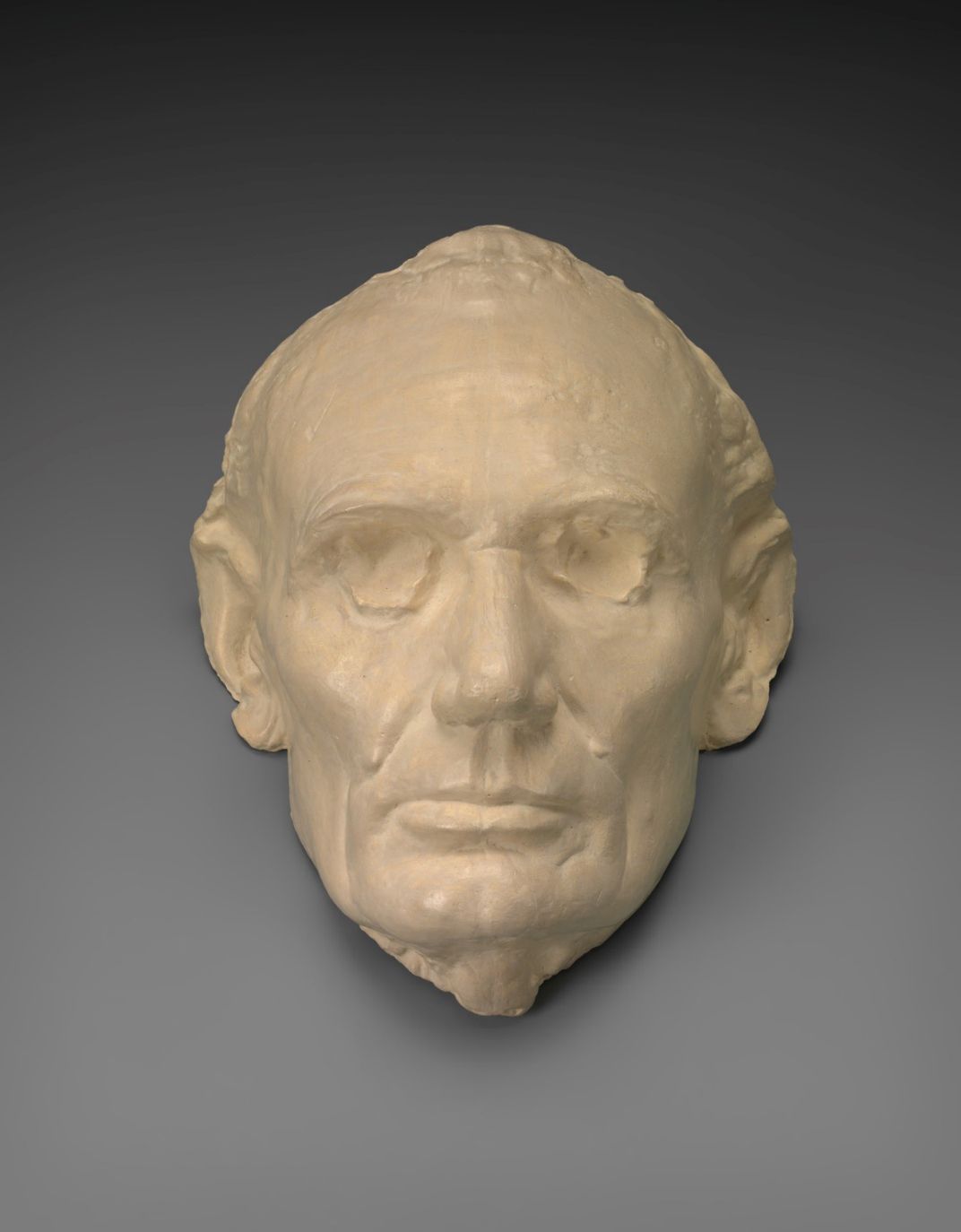

But because the sitter was no longer alive, Healy had to use several sources to paint the face. One of them was the life mask of the President that artist Leonard Volk had made in 1860. Life masks have been used for centuries to capture the features of the face. The plaster is applied wet to the face and let to dry so that it keeps the face contour. The goal of life masks is to guide the artist when rendering the face in the person’s absence. Volk did precisely this when he used the life mask as an aid in sculpting Lincoln’s face. Another source was the portrait of Lincoln that Healy had painted in 1860, days after the sitter’s Presidential victory. This is one of the very few images of Lincoln with a beardless look.

The 1887 painting was a commission from U.S. politician and diplomat Elihu Benjamin Washburne (1816 – 1887), who had been the U.S. ambassador to France between 1869 and 1877. Washburne wished to have a gallery of portraits of his favorite leaders at home, with most of whom he had negotiated diplomatically during the Franco-Prussian War (1870 –1871). Healy painted all the portraits, and the sitters were Otto von Bismarck, Léon Gambetta, Lord Lyons, and Adolphe Thiers. Healy resided in Paris at the time. He first received a commission to paint the portrait of Washburne and his wife in 1871, and in 1873 started working on the portrait gallery. While Healy was painting portraits for him, Washburne provided several letters of introduction to Healy; the letters were intended for U.S. ambassadors to foreign countries–like Russia— which the artist was visiting either for work or pleasure. The friendship between the diplomat and the artist proved very advantageous for both.

Washburne was a political ally of Abraham Lincoln and wanted to have a likeness of the iconic leader in his private residence. The 1887 portrait was Healy’s last replica of his “seated Lincoln,” composed initially as a study for a history painting called The Peacemakers. The artist executed the replica between January 12 and March 17, 1887, in his Parisian studio at number 64 of the rue de la Rochefoucauld. Very appropriately, the U.S. ambassador to France at the time, Robert Milligan McLane (1815 – 1898), visited Healy in his studio when the portrait was finished and praised the artist for the successful result.

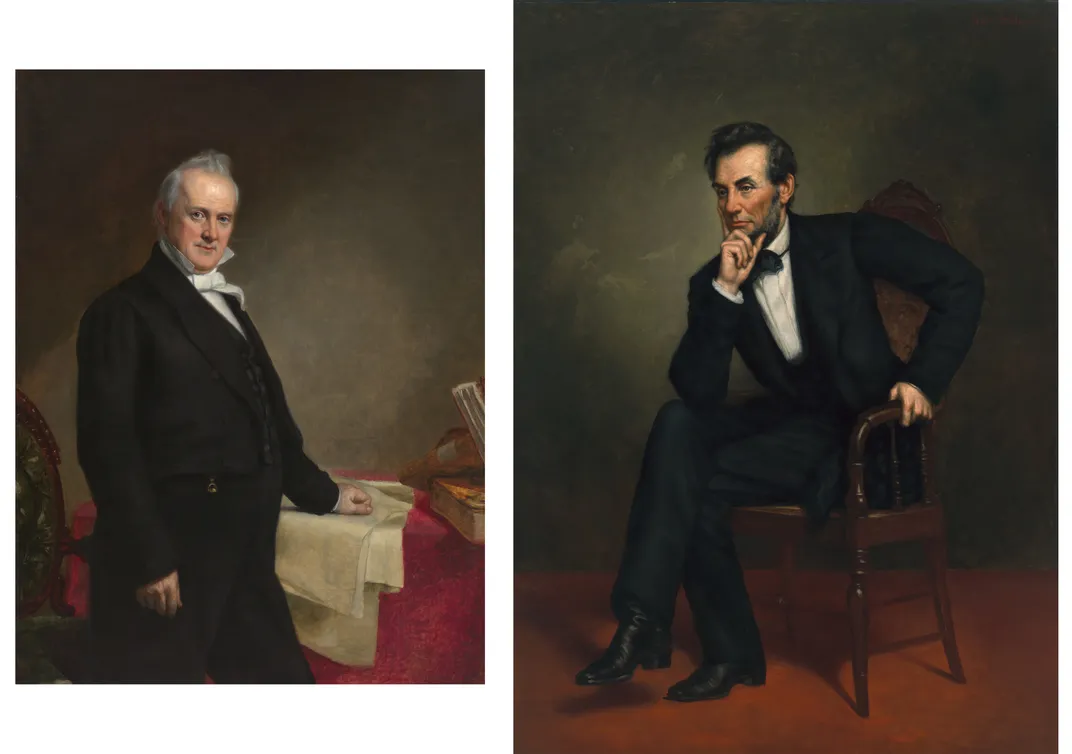

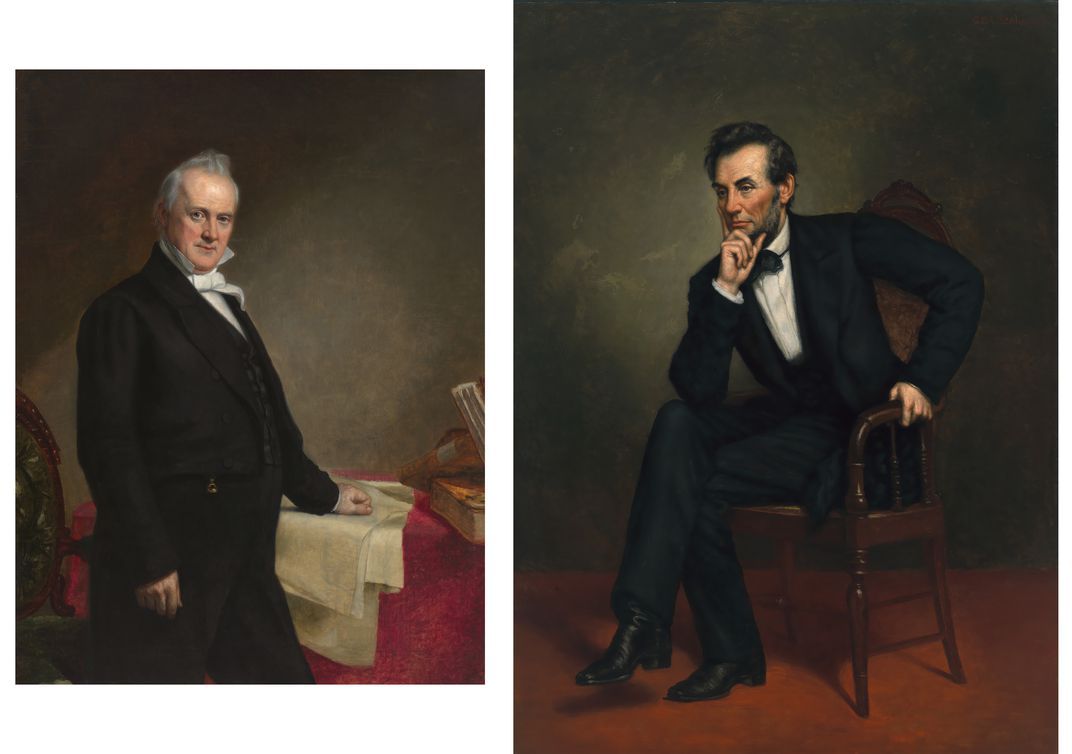

When Healy painted the 1887 version of the “seated Lincoln,” he had captured in life sittings the faces of eleven U.S. Presidents and had painted about sixty Presidential portraits between originals and copies. This was Healy’s last Presidential portrait. Relevant to this Lincoln portrait is the Presidential series that Healy painted in the late 1850s. It was a commission from Congress to furnish the White House with seven Presidential portraits depicting living Presidents. Six out of the seven paintings belong to the White House: John Quincy Adams, Martin van Buren, John Tyler, James Polk, Millard Fillmore, and Franklin Pierce. Congress never paid for the portrait of James Buchanan, due to the fact that he was sitting President at the time and was not popular among members of Congress; the painting ended up hanging in the same room as Lincoln’s likeness in the National Portrait Gallery.

The portrait of Buchanan presents a standard format for a Presidential likeness, and when comparing Healy’s Presidential portraits of Abraham Lincoln and James Buchanan, several differences can be noticed. Buchanan is standing and looks out straight to the viewer, while Lincoln is sitting down and looks away in a pensive fashion. Buchanan has a table next to him covered with documents, and he rests his hand on them to highlight the executive work he was doing; Lincoln appears in a bare space. Last but not least, Lincoln’s portrait is larger than Buchanan’s. This aspect highlights the tall facture of the sitter and adds a majestic quality to his portrait. The emptiness of Lincoln’s setting and his reflective attitude, in combination with the fact that Healy painted the portrait after the President Lincoln’s murder, confer an homage quality to the image. Lincoln the man becomes the Presidential martyr. The visual reminiscence that the portrait of former President Barack Obama by Kehinde Wiley holds with Lincoln’s portrait speaks volumes about the iconic power of Healy’s work. Ultimately, the placement of the portrait in the National Portrait Gallery’s Presidential Gallery, where it hangs in a central space with only the portrait of Founding President George Washington eclipsing it, confirms the status of Healy’s painting, not only as a masterpiece of portraiture but also as a monumental treatment of this political giant.

Un Homenaje Artístico para un Gigante Político: El Retrato Póstumo del Presidente Lincoln por G.P.A. Healy

El retrato del presidente Abraham Lincoln (1809 – 1865) que el artista estadounidense George Peter Alexander Healy (1813 – 1894) pintó en 1887 culminó una carrera dedicada a la creación de retratos presidenciales. La imagen, concebida años después de que el líder muriera, nos ayuda a entender tanto la práctica retratística del siglo diecinueve como el reto de pintar un retrato póstumo. El resultado es una imagen icónica de un gigante político que aún resuena hoy.

El retrato muestra a Lincoln sentado en una silla sencilla frente a un fondo abstracto. Lincoln viste un traje de oficina, con su característica pajarita atada en punta de diamante. Las faldas de la chaqueta asoman atrapadas por el reposabrazos. La silla de husillo proviene del mobiliario del tren presidencial de Abraham Lincoln, el cual Lincoln nunca usó en vida. Irónicamente, éste fue el vehículo ferroviario que transportó sus restos mortales desde Washington D.C. de regreso a su hogar en Springfield, Illinois. La simplicidad del diseño de la silla y el detalle de la falda atrapada sugieren una atmósfera de informalidad y descuido. Healy ha captado al retratado en un gesto pensativo, en una postura que presuntamente éste acostumbraba a adoptar para pensar. La postura corporal presenta una combinación incómoda de piernas cruzadas y brazo doblado sujetando el reposabrazos. Este gesto es una licencia artística para proyectar el busto del retratado hacia el espectador; la curva del brazo izquierdo repite las líneas arqueadas del respaldo y reposabrazos de la silla, destacando las ondulaciones para añadir elegancia a la composición.

El “Lincoln sentado” de Healy es un retrato póstumo, lo que significa que el retratado había fallecido antes de que el retrato fuera pintado. Para componer la figura inicialmente en 1867, Healy invitó a su estudio de Chicago a Leonard Swett -amigo de Lincoln- a posar como el líder. El hijo de Lincoln, Robert Todd, quien también residía en Chicago, proporcionó consejo al artista sobre cómo lograr que el retrato se pareciera a su padre. Healy era un artista metódico y minucioso que requería un mínimo de seis sesiones de posado de dos horas cada una en su estudio para pintar un retrato. Esta obra póstuma necesitó también varias sesiones para captar la postura corporal y el ropaje de forma adecuada.

Como el retratado ya no vivía, Healy tuvo que recurrir a fuentes diversas para pintar su rostro. Una de ellas fue la máscara facial de yeso del presidente que el artista Leonard Volk realizó en 1860. Este tipo de máscaras se han utilizado durante siglos para capturar los rasgos faciales. El yeso se aplica húmedo sobre el rostro y se deja secar para que selle el contorno facial. El objetivo de este tipo de máscaras es guiar al artista en la ejecución del rostro cuando el retratado se halla ausente. Volk hizo precisamente ésto cuando usó la máscara como ayuda para esculpir el busto de Lincoln. Otra fuente fue el retrato que Healy había pintado en 1860, días después de la victoria presidencial de Lincoln. Ésta es una imagen entre unas pocas que muestran a un Lincoln sin barba.

El cuadro de 1887 fue un pedido del político y diplomático estadounidense Elihu Benjamin Washburne (1816 – 1887), quien había ejercido como embajador estadounidense en Francia entre 1869 y 1877. Washburne deseaba tener una galería de retratos de sus líderes favoritos en casa que incluyera aquellos con los que Washburne había negociado diplomáticamente durante la guerra Franco-Prusiana (1870 –1871). Healy pintó todos los retratos, tres de ellos en París en donde él mismo residía, y uno en Alemania: Léon Gambetta, Lord Lyons, Adolphe Thiers y Otto von Bismarck. El artista primero recibió el pedido de pintar los retratos de Washburne y su esposa en 1871, y en 1873 comenzó a trabajar en la galería de retratos. Mientras Healy pintaba retratos, Washburne le proporcionó varias cartas de introducción; las cartas iban dirigidas a embajadores estadounidenses en el extranjero en países que el artista visitaba por trabajo o placer. La relación de amistad que el artista y el diplomático entablaron tenía claras ventajas para ambos.

Washburne era un aliado político de Abraham Lincoln en vida, y por esta razón deseaba tener su efigie. El retrato de 1887 fue la última réplica que Healy realizó de su “Lincoln sentado,” compuesto inicialmente como un estudio para su cuadro de historia titulado Los Pacificadores. El artista creo la réplica entre el 12 de enero y el 17 de marzo de 1887 en su estudio parisino del número 64 de la calle de la Rochefoucauld. Una vez terminada la réplica del retrato, Healy invitó al embajador estadounidense en Francia de entonces, Robert Milligan McLane (1815 – 1898), quien felicitó al artista por el resultado exitoso de su labor.

Cuando Healy pintó la versión del “Lincoln sentado” de 1887, éste ya había plasmado los rostros de once presidentes estadounidenses y había pintado unos sesenta retratos presidenciales entre originales y copias. Éste fue el último retrato presidencial que Healy pintó. En este contexto, es importante mencionar la serie de retratos presidenciales que Healy realizó a finales de 1850. Éste fue un pedido del Congreso estadounidense para decorar la Casa Blanca con siete retratos presidenciales. Seis de los siete retratos se encuentran actualmente en la residencia presidencial: John Quincy Adams, Martin van Buren, John Tyler, James Polk, Millard Fillmore, y Franklin Pierce. El Congreso nunca pagó por el retrato de James Buchanan puesto que éste era presidente cuando Healy pintó los retratos y su liderazgo no era popular entre los miembros del Congreso. Su retrato terminó expuesto en la misma sala de la Galería Nacional del Retrato en la que también cuelga el retrato de “Lincoln sentado.”

El retrato de Buchanan presenta un formato estándar de tipo presidencial, y cuando se lo compara con el retrato de Lincoln, se pueden discernir ciertas diferencias. Buchanan se encuentra de pie y mira directamente al espectador, mientras que Lincoln está sentado y mira hacia un lado de modo pensativo. Buchanan posa junto a una mesa cubierta con documentos y reposa su mano sobre ellos para recalcar la labor ejecutiva que estaba realizando; Lincoln aparece en un espacio vacío. Por último, el retrato de Lincoln es de mayor tamaño que el de Buchanan. Este aspecto enfatiza la gran altura de Lincoln y añade grandeza al retrato. El vacío del retrato Lincolniano y su actitud reflexiva, en combinación con el hecho de que Healy ejecutó el retrato después de que el presidente Lincoln fuera asesinado, confieren al retrato una calidad homenajística. Lincoln el hombre se convierte en el mártir presidencial. La reminiscencia visual que el reciente retrato del presidente Barack Obama por Kehinde Wiley exhibe demuestra el poder icónico de la obra de Healy. El emplazamiento del retrato Lincolniano en el centro de la Galería Presidencial de la Galería Nacional del Retrato, en donde sólo el retrato del presidente fundador George Washington lo eclipsa, confirma el estatus de la obra de Healy, no sólo como obra maestra sino como tratamiento monumental de este gigante político.