SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES

Who was Graceanna Lewis, Naturalist and Abolitionist?

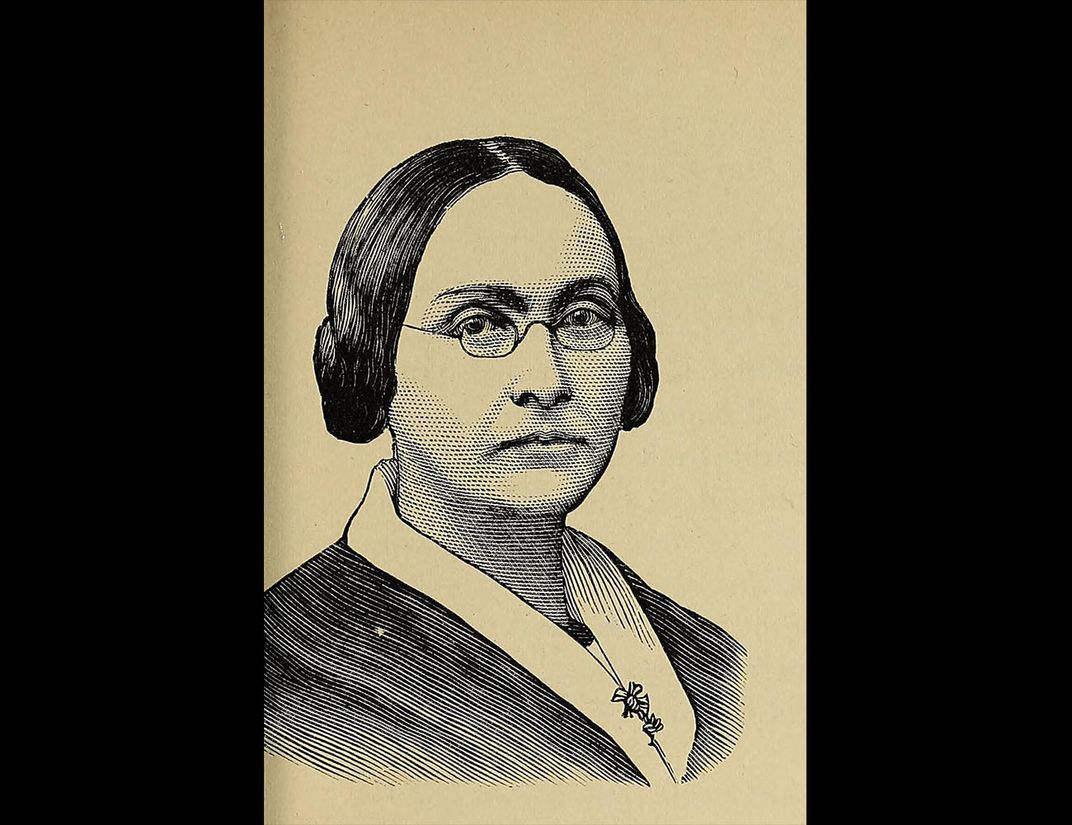

One of the first three woman to be accepted into the Academy of Natural Sciences, Graceanna Lewis broke barriers in science, but she was also remembered for playing a key role in the Underground Railroad.

:focal(591x745:592x746)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/undergroundra00stil_0801.jpeg)

“To her mind the truths of science seem revealed.”

That’s how Phebe A. Hanaford, author of Daughters of America (c. 1882), described naturalist Graceanna Lewis, one of the first three woman to be accepted into the Academy of Natural Sciences. But Lewis was not only one of the first professionally acknowledged women naturalists; she was also an abolitionist and social reformer who worked for the advancement of science as well as human rights. Researchers can find many publications by and about this intriguing woman in the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Digital Library and the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Born in 1821, Lewis benefitted from an egalitarian Quaker upbringing, one that encouraged education in daughters as well as sons. Lewis told Hanaford that she learned to love natural history from her mother, Esther Lewis. Esther had been a teacher before marriage and continued to educate her own young children, sending her daughters to nearby Kimberton Boarding School as they grew. There, Graceanna was influenced by Abigail Kimber, a woman botanist who had discovered and identified several species. In 1842, Lewis’ uncle, Dr. Bartholomew Fussell, started a new boarding school for girls, and Lewis came on board as a teacher. She taught astronomy and botany, among other subjects.

From her family, Graceanna Lewis inherited not only an interest in science and education but also a deep concern for social issues. Uncle Bartholomew was an active abolitionist, and the family formed a local auxiliary of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The Lewis sisters, Graceanna, Mariann and Elizabeth, were profiled in William Still’s The Underground Rail Road (1872), which described them as “among the most faithful, devoted, and quietly efficient workers in the Anti-slavery cause”.

One of Graceanna’s earliest publications, written in the 1840s, was “An Appeal to Those Members of the Society of Friends Who Knowing the Principles of the Abolitionists Stand Aloof from the Anti-Slavery Enterprise”. It implored fellow Quakers to join the Anti-Slavery movement. The Lewis farm in Pennsylvania became a frequent and successful point on the Underground Railroad, described in detail by Still. The family helped transport those seeking freedom and provided clothes and supplies.

Eventually, Lewis moved away from the family farm to Philadelphia. She had studied birds and other natural sciences on her own, but this move allowed her to take advantage of the specimen and library collections at the nearby Academy of Natural Sciences, and it propelled her into a network of naturalists. In 1862, she met John Cassin, ornithologist and curator of birds at the Academy. Cassin had written, with George N. Lawrence and the Smithsonian’s own Spencer Baird, The Birds of North America (1860), a work Lewis found particularly inspiring.

Cassin would be an invaluable friend and mentor to Lewis, even naming a bird for her, Icterus graceannae, the White-edged oriole. Lewis also corresponded frequently with Baird for years, seeking advice and asking for copies of Smithsonian publications. In 1870, the year after Cassin’s death, Lewis became one of the first three women admitted as members to the Academy.

Lewis had channeled her interested in ornithology into her first scientific publication, Natural History of Birds : lectures on ornithology, in ten parts (1868). It was intended as an inexpensive overview of American birds for a general audience. In it, she also proposed a new classification scheme based on embryology, the characteristics of eggs. Unfortunately, only the first part was published, as funding for the remaining nine was never secured. She continued to research and publish on birds, alongside the leading naturalists of her time. Her articles in The American Naturalist, “The Lyre Bird” (August 1870) and “Symmetrical Figures in Birds’ Feathers” (November 1871) are available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

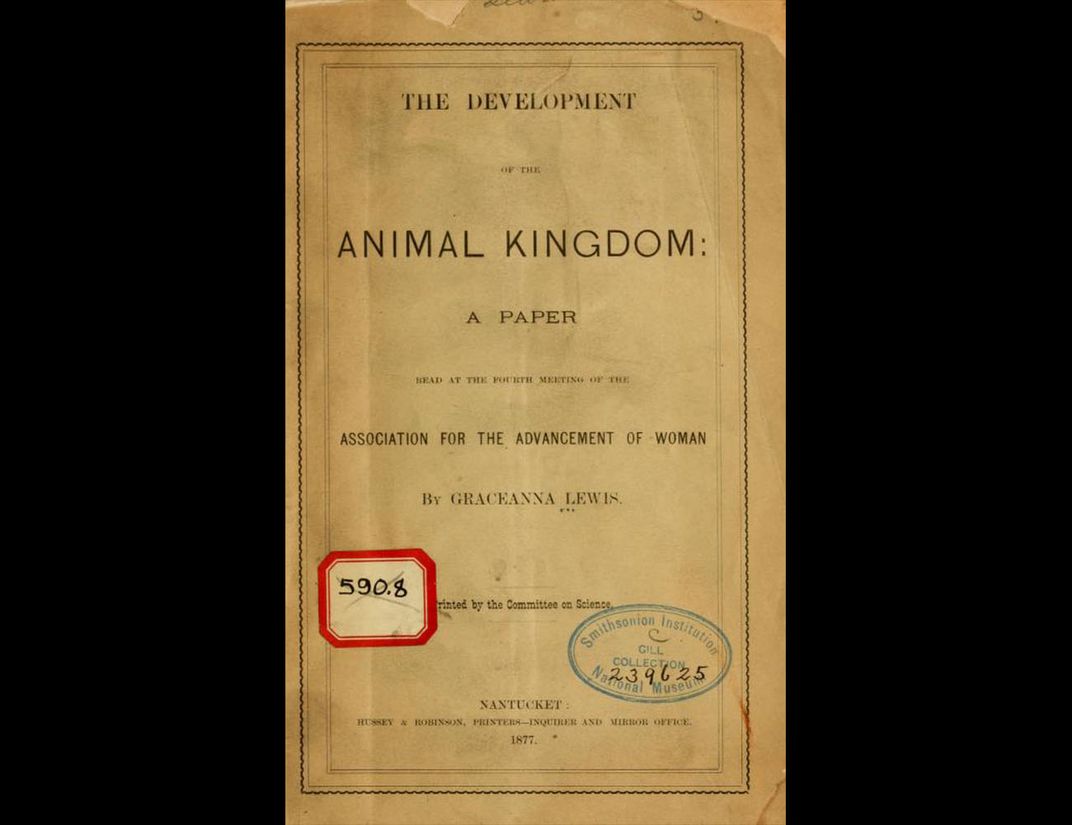

Lewis’ interests and publications grew beyond ornithology, into the classification of natural history and a “tree of life”, which she exhibited at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876. The Development of the Animal Kingdom (1877), available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library, is a twenty-page overview of her theories. It was prepared for the fourth meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Women. The group was formed in 1868 with the goal of presenting practical methods for improving women’s role in society, including education on a variety of subjects. Unsurprisingly, Lewis was active on the group’s Committee on Science.

Lewis told Phebe A. Hanaford in 1882, “I feel that my life’s work is before me, in lecturing on zoology to girls just blooming into womanhood”. For the next twenty years, Lewis continued to teach and write about various natural history topics. Her article “On the Genus Hyliota”, discussing the distinction of two rare African birds, was published in The Annals and magazine of natural history in 1883. Her social reform interests turned to temperance and suffrage, serving stints as secretary for her local chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and suffrage association.

Graceanna Lewis died in 1912 in Media, Pennsylvania at the age of 90. Her contributions to both science and social progress leave a remarkable and inspiring legacy.

Further Reading from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives:

Baird, Spencer Fullerton, John Cassin and George N. Lawrence. The Birds of North America (1860).

Baird, Spencer Fullerton. Spencer Fullerton Baird Papers. Record Unit 7002. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Hanaford, Phebe A. Daughters of America (1883).

Lewis, Graceanna. The Development of the Animal Kingdom (1877).

Lewis, Graceanna. “On the genus Hyliota”. The Annals and magazine of natural history, Series 5, Volume 12, No. 67, pp. 210-212.

Still, William. The Underground rail road (1872).

Warner, Deborah Jean. Graceanna Lewis, scientist and humanitarian (1979).

Other resources:

Bonta, Marcia. “Graceanna Lewis, Portrait of a Quaker Naturalist”. Quaker History, Volume 74, Number 1, Spring 1985, pp. 27-40.

Lewis-Fussell Family Papers, SFHL-RG5-087, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College

Lewis, Graceanna. “An appeal to those members of the Society of Friends who knowing the principles of the abolitionists stand aloof from the anti-slavery enterprise”. [between 1840 and 1849?].

Lewis, Graceanna. “The Lyre Bird” The American Naturalist (August 1870), pp 321.

Lewis, Graceanna. “Symmetrical Figures in Birds’ Feathers” . The American Naturalist (November 1871), pp. 675-678.

Truitt, James. “Digitizing the Papers of Graceanna Lewis, Ornithologist and Activist”. Cassinia. No. 77 (2017-2018), pp. 40-41.