SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES

How Yellowstone Was Saved by a Teddy Roosevelt Dinner Party and a Fake Photo in a Gun Magazine

An article from Forest and Stream in 1894 included chilling photos of slain buffalo in Yellowstone Park. It helped pass an act outlining punishment for poaching on public lands. But the photos were fakes.

:focal(499x566:500x567)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/reportofunitedst1887unit_0511_crop.jpg)

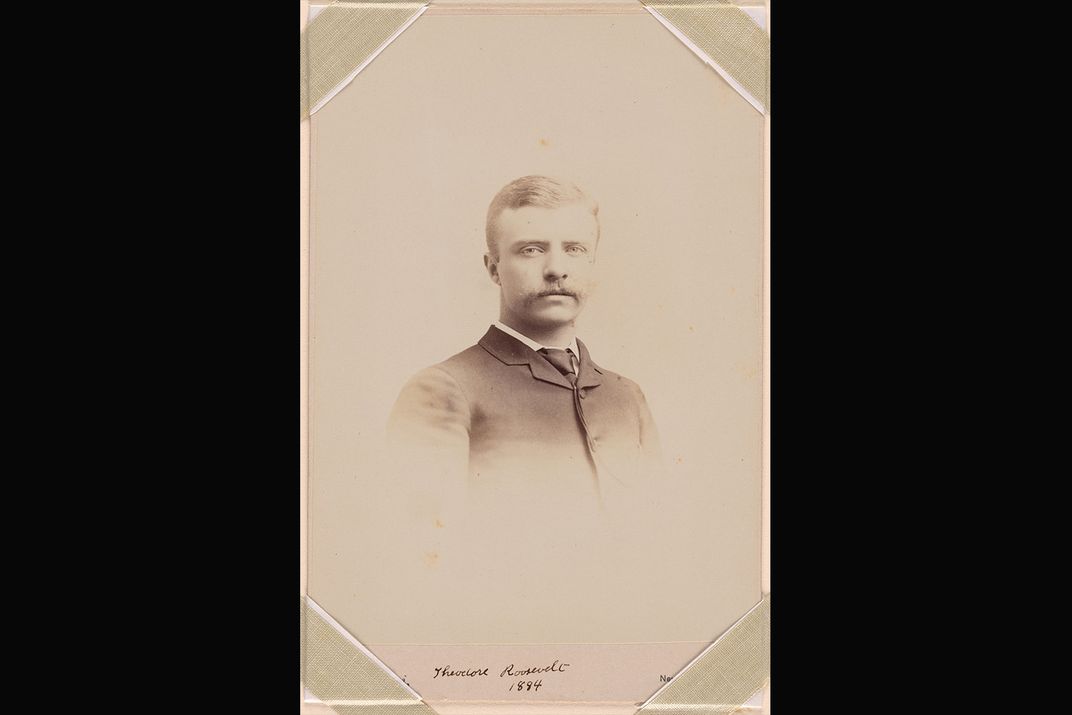

A chill rain drizzled over guests arriving at Bamie Roosevelt’s midtown brownstone near the corner of Madison Avenue and East 62nd Street in December 1887. There weren’t many of them, but all had two things in common: they were New York’s most influential and rich social elite, and they all loved hunting big game. All were hand-picked by the hostess’s brother, Theodore Roosevelt, to facilitate his newfound interest in the conservation of the American West. That small gathering became the first domino in a long line that ended in the protection of Yellowstone, the first environmental advocacy group in the US, and the creation of the American National Parks system.

Teddy was in the nadir of his career. His 3rd place finish in the New York City Mayoral race foretold doom in the realm of politics. His North Dakota ranch was devastated by winter storms (later known as The Big Die-Up) and on the verge of collapse. His latest book on his Western adventures, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, received a middling review in the popular sportsmen’s magazine, Forest and Stream, which praised his prose but harped on “the author’s limited experience” (Forest and Stream v.24, pg. 451). T.R. was evidently so incensed at the aspersions on his Western manliness that he showed up at the Forest and Stream editorial offices in New York to demand to speak to whoever wrote the article. That very visit led to Roosevelt’s midtown dinner party.

The evening may have gone something like this: first, he plied his guests with the rich bounty of his table and cellar with many toasts and courses. Roosevelt’s glass was unlikely to contain much alcohol (there was even a later court case about his abstention from drunkenness), but his hard-drinking younger brother Elliott and others may have partaken in the bon-vivant cocktails popular at the time. Then during the game course traditional to late 19th century gatherings, the conversation is adeptly steered by Teddy to their subject of common interest: hunting. Over yet another toast, Roosevelt proposes the formation of club named for America’s two most legendary hunters and committed to their shared values: fair chase, preservation of game, and “manly sport with the rifle.” Thus was formed the Boone and Crockett Club.

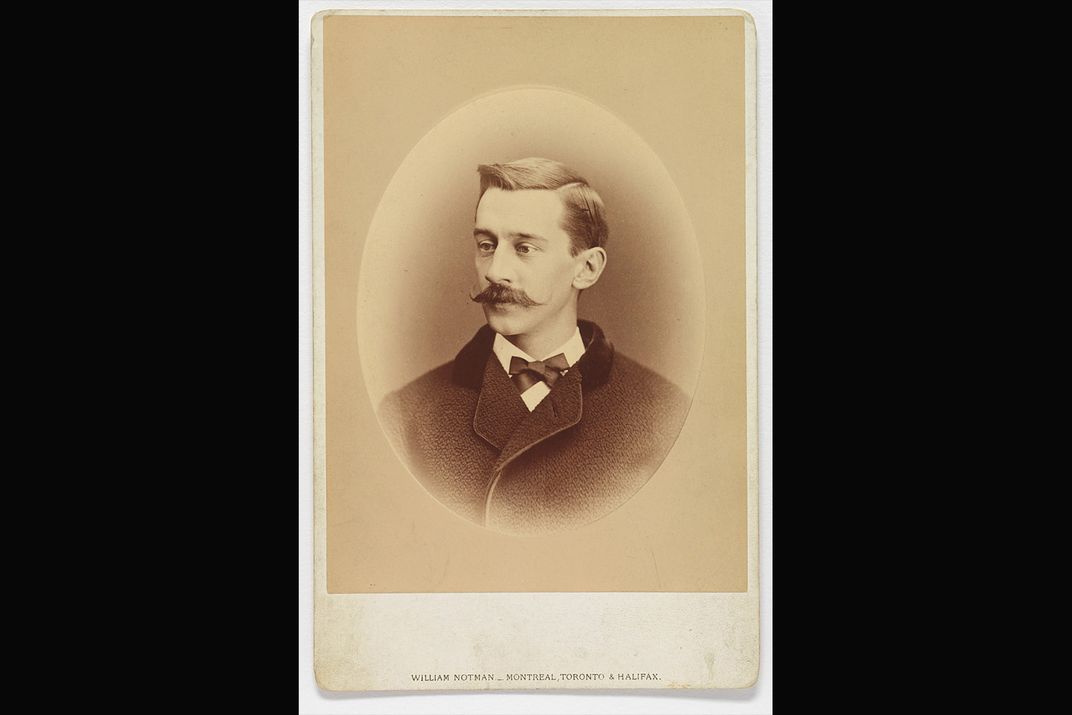

It could have ended there, with a private club whose members were required to have killed a large North American animal according to their own rules of engagement. But this group would grow in fame because of one of its founding members: George Bird Grinnell. At the time of this gathering, Grinnell stood out among the invited guests for his anonymity. He wasn’t a millionaire like Rutherford Stuyvesant or John Jay Pierrepont, or a famous man of the West like Albert Bierstadt or Bronson Rumsey, or an influential socialite like J. Coleman Drayton or Archibald Rogers. George Bird Grinnell was just a scientist, interested in joining expeditions to the West as a naturalist and studying the Native peoples of that region. He did have two qualities that drew Roosevelt to him, though: he loved Yellowstone and he edited a sportsmens’ magazine called Forest and Stream. Yes, Grinnell was the very person who published the backhanded review of Roosevelt’s book. Their confrontation led to a friendship that hatched the plan to gather the powerful crew of socialites and advocates for the West.

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives holds an extensive run of Forest and Stream, beginning with the first volume in 1873. While our physical copies are located in the Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex location, readers can find digitized versions of Volumes 1- 95 online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ work during the pandemic has been improving metadata in the Biodiversity Heritage Library, helping titles like Forest and Stream become more accessible to the world. Grinnell became editor-in-chief of the publication in 1881, using it as a tool to raise awareness of conservation issues, especially of his beloved Yellowstone, which he visited in 1875 as part of the Ludlow Expedition.

But in 1888, Yellowstone was in big trouble. Even though the area had achieved National Park status (the first in the US) in 1872, the designation was toothless. Poachers ran rampant, railroad companies eyed its majestic passages as thruways for their locomotives, and the Army had set up a fort to make war on the Native people of Yellowstone and deny them rightful access to their land. So Grinnell and the Boone and Crockett Club began a petition to Congress, published in the pages of Forest and Stream among its coverage of hunting trips, fishing tips, and shooting competitions. First a column of names, then page after page of supporters, many cajoled into participation by the Boone and Crockett Club’s socially influential measures, like Roosevelt and his chums, as evidenced by the frequent appearance of high-level New York socialites on these lists, many of whom included acquaintances of the likes of Stuyvesant and Drayton.

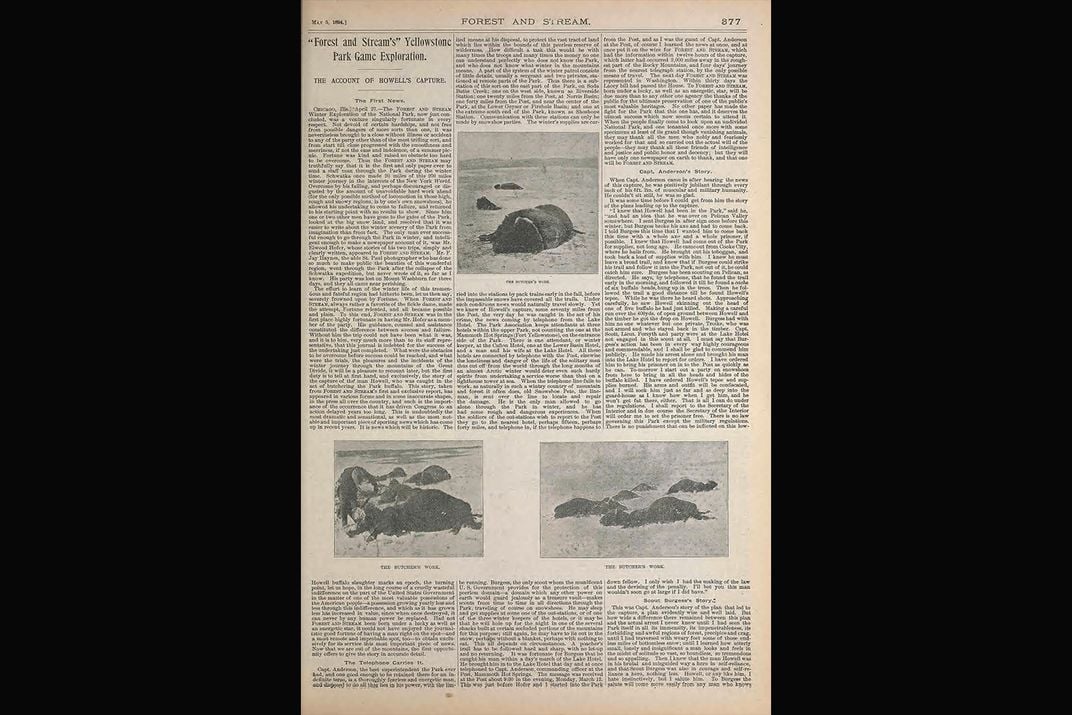

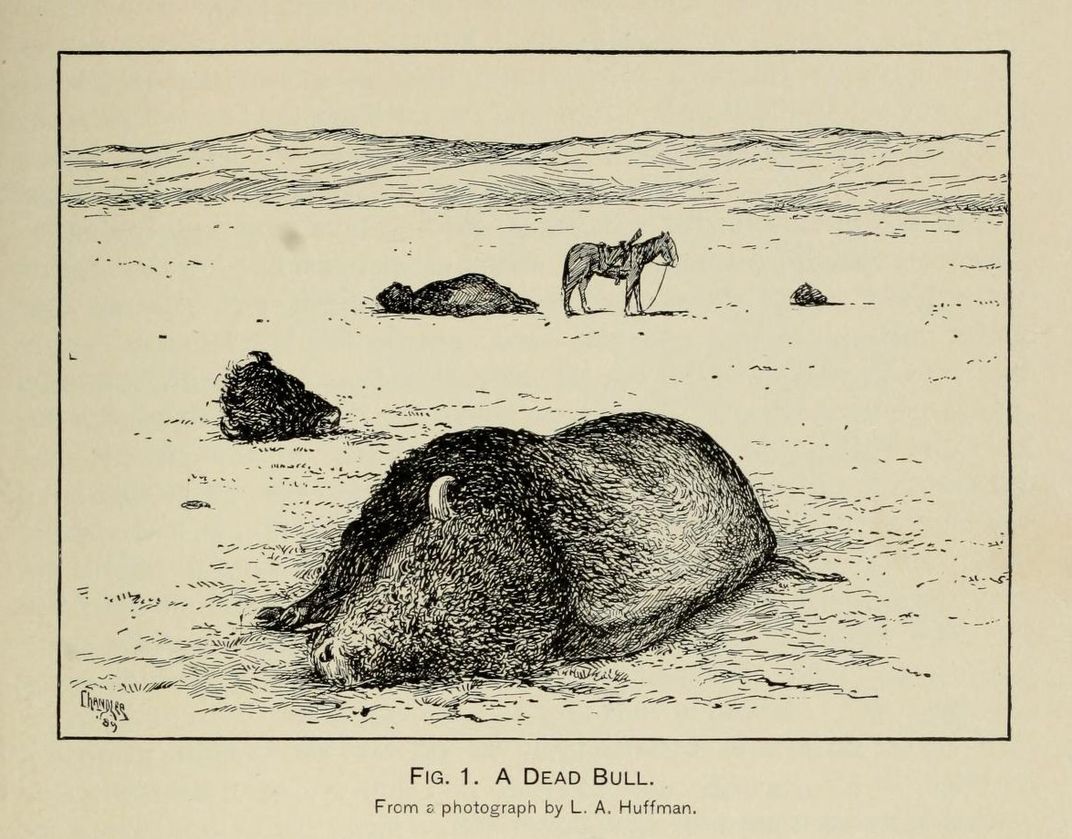

But all that effort didn’t move Congress to act, despite year after year of attempts. That all changed on May 5, 1894, when Forest and Stream published an account of the capture of an infamous poacher, Edgar Howell. He had previously eluded apprehension because the U.S. Cavalry, who was tasked with patrolling the park, had to catch a perpetrator in the act of poaching in order to pursue and arrest them. Unbelievably, the Army only had a single patrolman for the entirety of Yellowstone. This patrolman happened to be near Howell during a shooting and got the drop on the poacher and was able to call for help on the new-fangled telephone. The story was covered in full by the lone correspondent to as yet overwinter in Yellowstone: Emerson Howe. But it wasn’t Howe’s breathless reporting of the killing of dozens of buffalo that spurred national outrage; it was the images of Howell’s animal victims left lying in piles on the plain, titled by Grinnell as “The Butcher’s Work.”

Except they weren’t pictures of the bison that Howell had killed. These pictures were used in an Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution from seven years earlier. Grinnell was apparently sent the original photographs by William T. Hornaday, whose collection of living animals formed the basis of the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park. No record has yet been found illuminating how or why the decision to fake the photographs was made. Of important note, Grinnell’s trickery wasn’t necessary to convict Howell, who confessed and never amended his ways.

The ruse was effective though: only days later Congress passed the Act to Protect the Birds and Animals in Yellowstone National Park, and to Punish Crimes in Said Park. Known as the Lacey Act of 1894, the law finally outlined a punishment for poaching on public lands. The first person convicted under the Act was none other than Edgar Howell.

Roosevelt went on to strengthen the protections of public lands, campaigning on conservation for the Vice Presidency in 1900 and later as President, establishing the National Parks system that currently protects not just Yellowstone, but 85 million total acres of American lands. T.R. continued to have a close relationship with Forest and Stream, contributing articles heralding conservation reforms and hosting organizational meetings at his home in Oyster Bay.

Further Reading: