SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES

Tracing Anthropologist Zelia Nuttall Through Smithsonian Collections

A remarkable Mexican American scholar, Zelia Nuttall she helped change the conversation around pre-Columbian cultures. Researchers can trace her work through publications held in the collections of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and repositories around the Institution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/0a/8f0ad176-2332-4064-8a6f-c4a57c7d4a96/img_9096.jpg)

Anthropologist Zelia Maria Magdalena Nuttall was an expert in Mesoamerican people and artifacts. A remarkable Mexican American scholar, she helped change the conversation around pre-Columbian cultures. Many of her publications are held in the collections of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and traces of her work can be found in repositories around the Institution.

Nuttall was born in San Francisco in 1857 to a family with both wealth and deep Mexican ties. Her father, Robert Nuttall, was an Irish physician. Her mother, Maria Magdalena Parrott, was born in Mexico, the daughter of a diplomat banker. It is said that Zelia first became intrigued with Mesoamerican civilizations when her mother gifted her a copy of The Antiquities of Mexico, a beautiful facsimile of ancient codices compiled by Lord Gainsborough. Though her family eventually left California for Europe, Nuttall’s natural curiosity was complemented by a solid education by private tutors, and she was fluent in both Spanish and German.

Nuttall took her second trip to Mexico in 1884, accompanied by family. She collected small terra cotta heads near Teotihuacan, which would become the subjects of her first article, published in The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts in 1886. Contemporary anthropologists had not given them much attention, considering them puzzling novelties. But Nuttall marveled at the diversity of them, praised their craftsmanship, and attempted to classify and explain them.

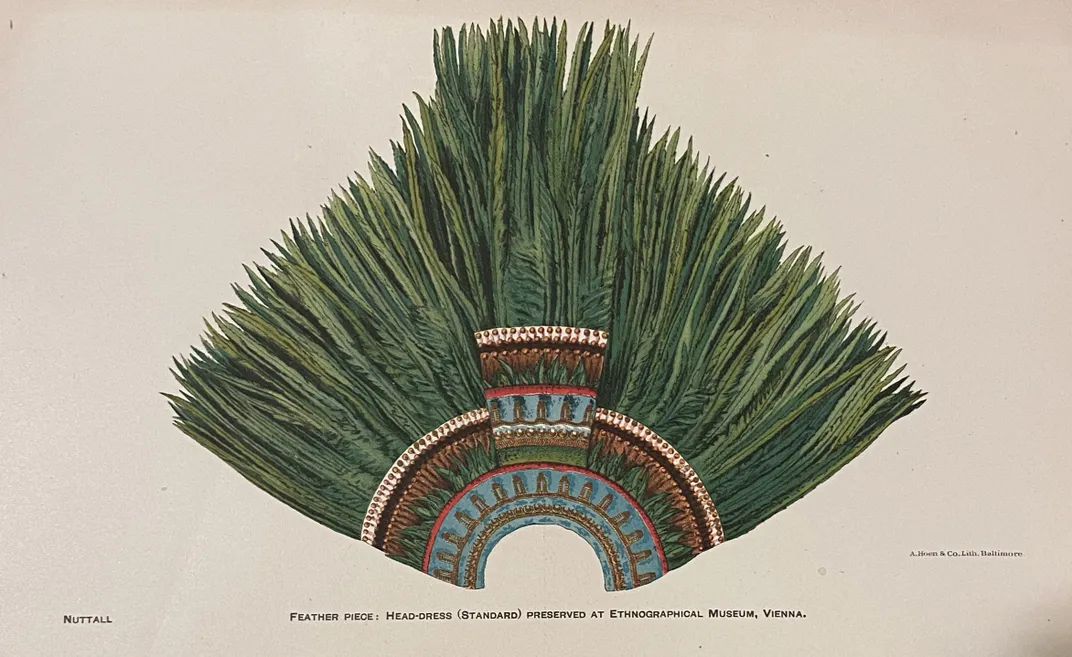

Shortly after, she became acquainted with Frederick Ward Putnam of the Peabody Museum of Harvard and was offered the role of Special Assistant in Mexican Archeology. She published several articles and books towards the end of the 19th century, including Ancient Mexican feather work at the Columbian historical exposition at Madrid (1895) (available online via the Library of Congress). In 1901, she published a lengthy comparison of cultures and religions in The fundamental principles of Old and New World Civilizations (available online via Brigham Young University). The book, supported by Putnam, suggested that since many cultures around the world shared similarities, perhaps ancient European and Asian civilizations interacted with ancient Americans. Though later discredited, the concept did help adjust perceptions of Mesoamerican cultures, often considered unrefined, and place them on the same level as the Egyptians and Greeks.

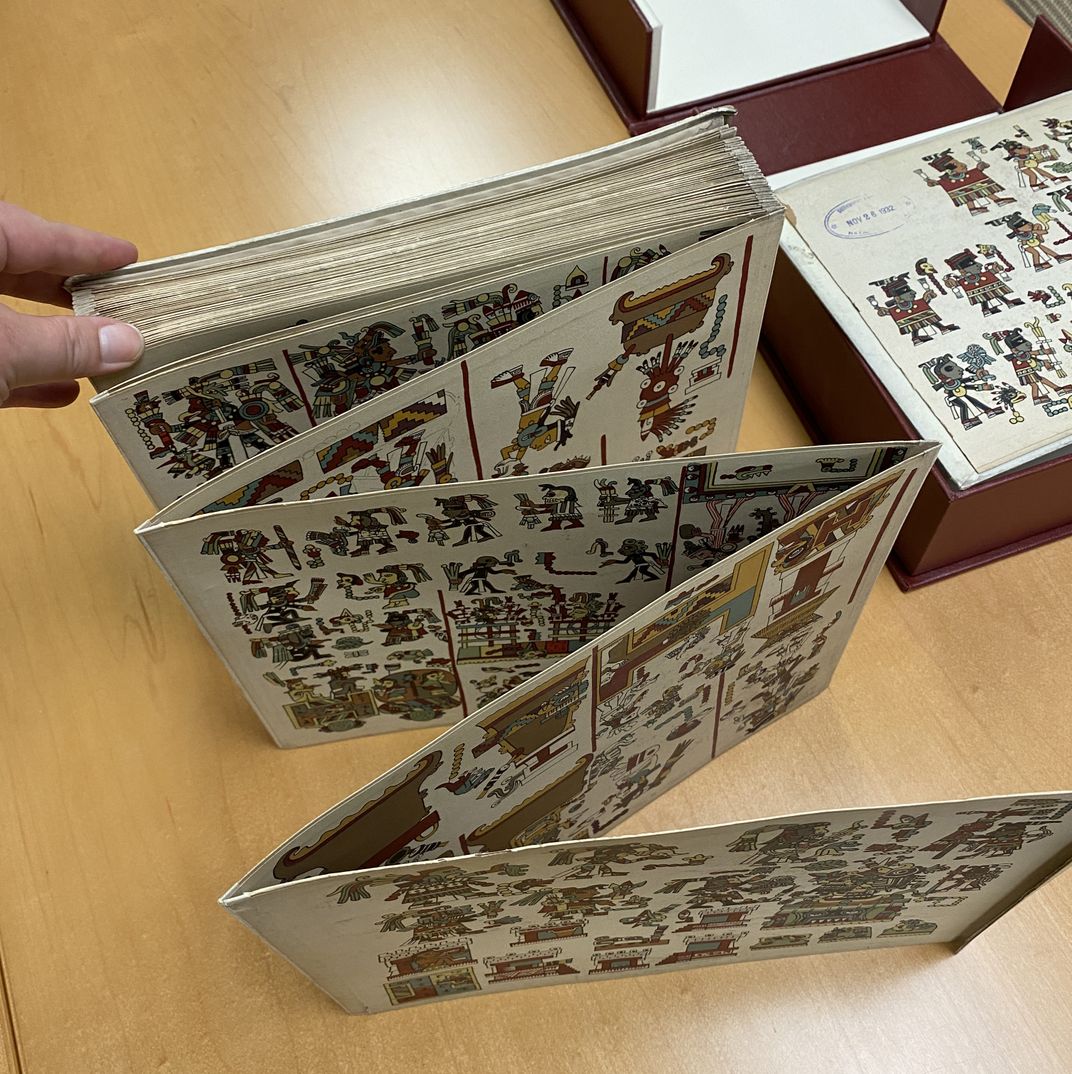

One of Nuttall’s most notable works is her namesake Codex Nuttall, a translation and facsimile of a 13th century Mixtec folding screen book. Nuttall traveled to England to research the original, then owned Robert Curzon, 14th Baron Zouche and now in the collections of the British Museum. The codex had previously been dismissed, thought to be a children’s book or one of little consequence, but Nuttall found it to be the “most superb example of an Ancient Mexican historical manuscript” she had ever seen. Nuttall translated the codex, realizing that one side tells the history of important Mixtec centers and the other side recording the genealogy, marriages, and political accomplishments of the ruler Eight Deer Jaguar Claw.

Seeing the presentation copy of the Codex Nuttall in our John Wesley Powell Library of Anthropology you can’t help but admire Nuttall’s attention to detail in her reproduction. In the facsimile, Nuttall recreates the experience of the original folded manuscript. Though the original was no longer protected by sturdy end pieces, she suspected they had been at one time and designed parchment covers for her version in “strict accordance with native methods”.

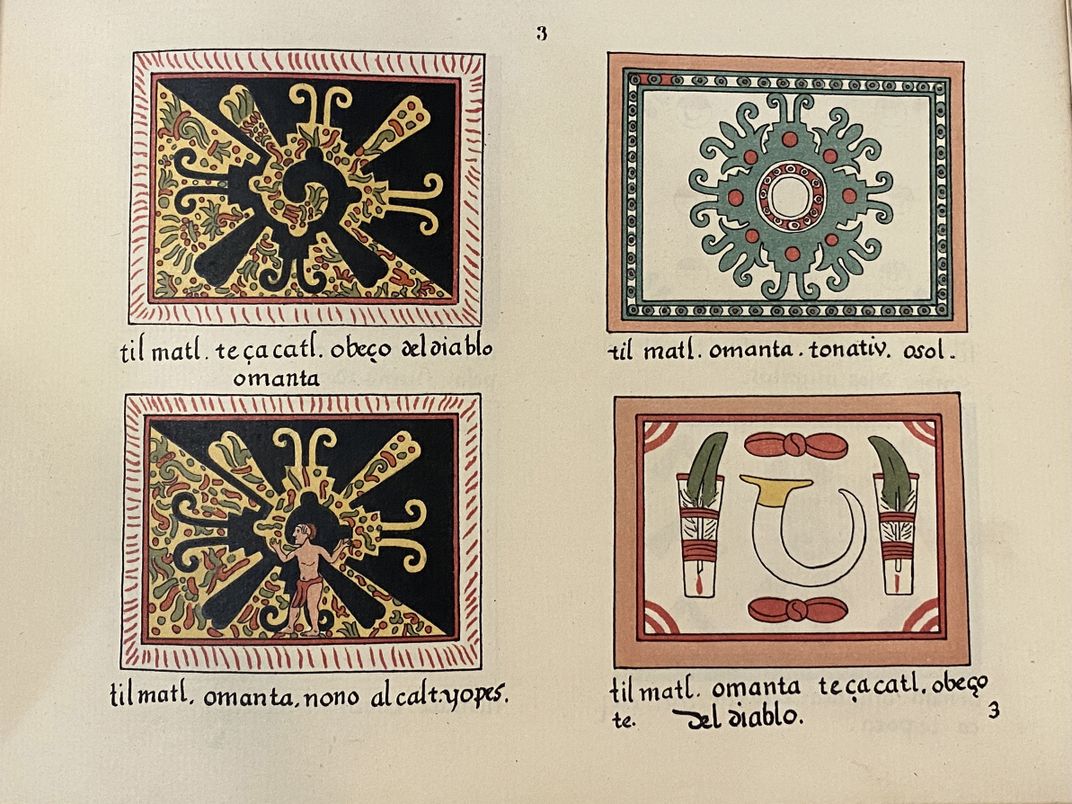

In 1903, Nuttall published another facsimile and translation, this time of the “Magliabecchi manuscript” in The book of the life of the Ancient Mexicans (see the University of Virginia’s copy online). The source manuscript, once owned by Antonio Magliabecchi, was created sometime during the 16th century, likely by indigenous scribes at the behest of Spanish clergy, to recreate an even earlier codex. Nuttall first encountered it in 1890 at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze in Florence while searching for Mesoamerican works in European libraries. According to her preface, transcribing and researching the manuscript led Nuttall to important discoveries of the Ancient Mexican Calendar System which “changed the current views held on the subject”.

Though archaeology was often a part of Nuttall’s work, it wasn’t until 1910 that she endeavored to lead an official dig. She had researched the history of La Isla de Sacrificios, a small island near Veracruz, where Bernal Diaz had reportedly witnessed ceremonial sacrifices in the 1500s. Nuttall made a quick visit, during which she unearthed pottery and the partial walls of a structure. She reported her findings to the Mexican government and requested permission to return for a more comprehensive excavation but was stymied by Leopoldo Batres, the Inspector of Monuments. Weeks later Bartres visited La Isla de Sacrifios himself and claimed the discovery as his own. Nuttall detailed her experience in American Anthropologist and Batres issued a pretty scathing (and a bit sexist) rebuttal. In La Isla de Sacrificios, la Señora Zelia Nuttall de Pinard y Leopoldo Batres (1910), available in our Digital Library, Batres disputes her claims and suggests Nuttall suffered from “el histerismo femenino” (female hysteria).

Nuttall was part of an extensive network of anthropologists, archaeologists, and other scientists throughout her career. She was a member of the Archeological Institute of America and the American Philosophical Society and among the first women to represent the United States in the International Congress of Americanists. Nuttall’s correspondence with colleagues and other papers are held by several archival repositories at the Smithsonian. The National Anthropological Archives holds manuscript materials related to the Codex Nuttall and other aspects of Nuttall’s work. Nuttall’s letters to George Hubbard Pepper, an anthropologist with the Bureau of American Ethnology and the National Museum of the American Indian, are held by the National Museum of the American Indian. The Archives of American Gardens has photos of Nuttall’s gardens at her home in Mexico, Casa Alvarado. Our own Smithsonian Institution Archives includes letters from Nuttall to curator George Brown Goode following up on the possible publication of her aforementioned article on Ancient Mexican feather work.

Items collected by Nuttall have also found a home at the Smithsonian. The National Museum of Natural History’s Botany collections include samples of Chenopodium berlandieri or lamb’s quarters, collected near Mexico City. The National Museum of the American Indian holds Mixtec artifacts collected by Nuttall, including skirts, sashes, and beads.

Nuttall died in 1933, with a number of professional titles, accomplishments, and historical discoveries to her name. The bibliography in her obituary in American Anthropologist lists over 70 publications. Through her work, she examined and explained Mesoamerican civilization and uncovered indigenous art, technology, and culture previously lost to colonial forces.

Further Reading from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives:

Batres, Leopoldo. La Isla de Sacrificios, la Señora Zelia Nuttall de Pinard y Leopoldo Batres (1910).

Chiñas, Beverly Newbold. “Zelia Maria Magdalena Nuttall”, Women anthropologists: a biographical dictionary (1988).

Gainsborough, Edward. The Antiquities of Mexico (1831-1848).

Nuttall, Zelia. Ancient Mexican feather work at the Columbian historical exposition at Madrid (1895).

Nuttall, Zelia. The book of the life of the Ancient Mexicans (1903).

Nuttall, Zelia. Codex Nuttall (1902).

Nuttall, Zelia. The fundamental principles of Old and New World Civilizations (1901).

Other Resources:

McNeill, Leila. “The Archaeologist Who Helped Mexico Find Glory in Its Indigenous Past”, Smithsonian.com (November 5, 2018).

Nuttall, Zelia. “The Terracotta Heads of Teotihuacan”. The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1886), pp. 157-178.

Nuttall, Zelia. “The Island of Sacrificios”, American Anthropologist, 12 (1910): 257-295.

Tozzer, Alfred M. “Zelia Nuttall”. American Anthropologist, 35 (1933): 475-482.