SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES

Some Archival Career Advice

We receive dozens of inquiries every year from students and recent graduates about the archives. In honor of American Archives Month, archivist Jennifer Wright answers a few of the most commonly-asked questions.

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives receives dozens of inquiries every year from students and recent graduates about the archives profession and how to become an archivist. Since this is such a popular topic, we decided to make our responses to the most common questions available to a wider audience. While the responses below are intended to address the archival profession in general, they ultimately reflect my own experiences and those of my immediate colleagues.

What does an archivist do?

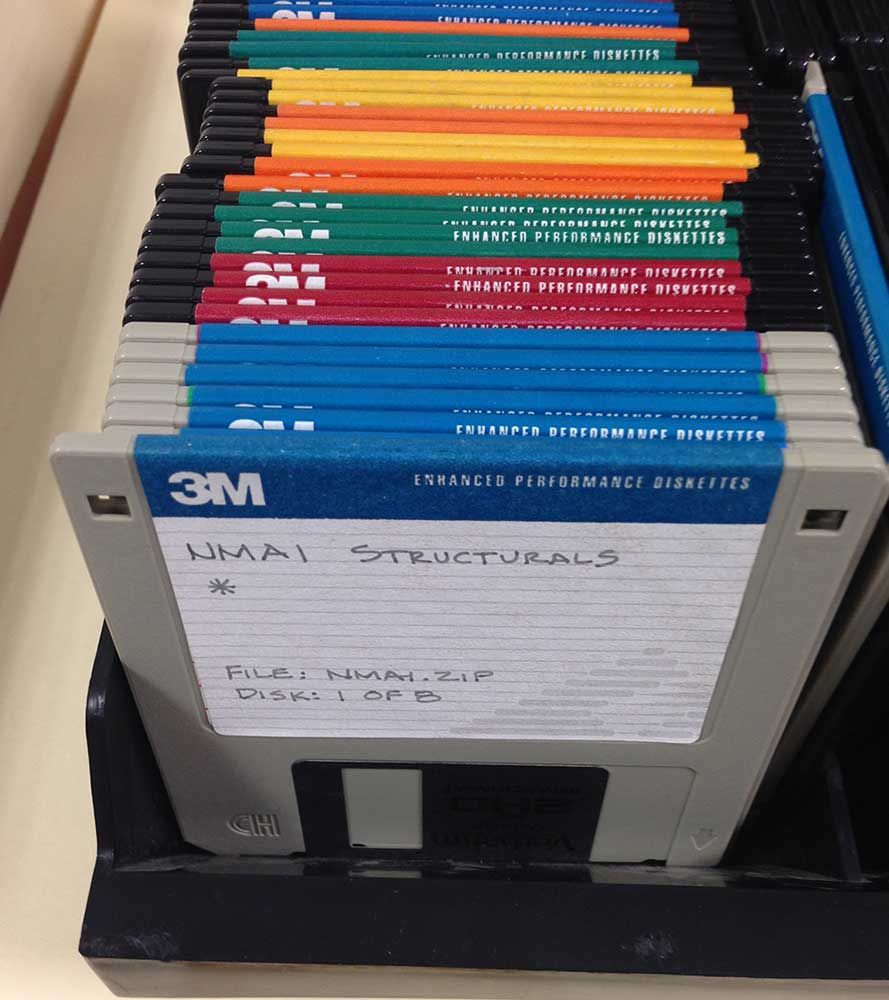

Archivists perform a wide variety of tasks. In a smaller archives, a few individuals may do everything while, in a larger archives, archivists may specialize in specific aspects of the work. Traditionally, an archivist works with donors or the staff of its parent institution to acquire new collections; organizes and rehouses collections (also known as processing); describes collections and writes finding aids; and assists researchers in using the collections. Some archivists specialize in the acquisition, management, description, and preservation of born-digital files, web-based content, photographic materials, or audiovisual recordings. Other aspects of the job may include records management, digitization, metadata creation, public outreach, research, writing, or teaching.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

I enjoy learning about a wide variety of topics within the collections I process. I also enjoy going behind the scenes and exploring our museums and research centers from the inside out.

What qualities are employers looking for in an archivist?

Many employers will be looking for applicants who can work both independently and on a team; demonstrate strong research and writing skills; exhibit attention to detail; are creative problem solvers; and show a natural curiosity. Many positions will require data management, digitization, and digital preservation in addition to working with digital files for the purposes of appraisal and reference. A solid background in basic technical skills will be essential. Some employers may also be looking for knowledge of a particular topic related to their collection, such as local history or aviation. Intern, volunteer, or other hands-on experience will often be a critical factor in deciding which applicant to hire. The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives offers several internship programs each year, as do other archival repositories around the Institution.

What degree do you need to be an archivist?

Many, but not all, employers will require a Master of Library Science, a Master of Library and Information Science, “or equivalent.” A Master of Library Science was once a common degree for new archivists, but as traditional library school programs have evolved, many universities have renamed the degree (often combining the terms “library” and “information”) or have created a separate degree for the archives, records, and information management (sometimes called a Master of Information Studies). A very limited number of universities have even created a degree specifically for archival studies. Employers generally recognize that these degrees tend to be similar. When deciding on a graduate school, look at the courses that are included in the curriculum, not just the title of the degree offered. Other common graduate degrees held by archivists include public history and museum studies. Some positions may only require an undergraduate degree, but a graduate degree will likely be “preferred.”

What other subjects are helpful in your job?

The research and writing skills gained through history, English, and other liberal arts classes are helpful. A second language can also be useful in a setting where non-English documents are found in collections. Archival collections can deal with any topic though, so there is no way to tell which subjects may be useful later. Some employers may require archivists to have a background in a specific subject matter while others will be looking at professional skills first and assume the subject matter will be learned on the job. Furthermore, workshops or introductory courses in information technology skills such as database design, programming, or data forensics could be assets in many different settings.

What recommendations do you have for a future archivist?

Whether you are just beginning your archival training or will be looking for a job soon, periodically check the job listings. Take note of the requirements and preferred qualifications for positions that interest you. More than any advice, these listings will give you a good idea of what skills and knowledge you need to acquire in order to reach your ultimate goals. Also, do not limit yourself to a specialty. Taking specialized courses will make you competitive for certain types of jobs, but be sure to take fundamental courses in all aspects of archival work to meet the minimum requirements for the largest number of jobs. In addition, whenever possible, take courses from adjunct professors who also work in an archives. From these professors, you will often learn how to make decisions about priorities in settings where budget and staff are limited.

Be sure to take advantage of the numerous online resources available to new and future archivists, many of which are free to access. Professional organizations such as the Society of American Archivists, ARMA International (for records management, information management, and information governance), the National Association of Government Archives and Records Administrators (NAGARA), the Association for Information and Image Management (AIIM), and the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA) are all great places to begin.