SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES

Go West! Then Back to the Future

History is full of narratives and even those narratives have a history. As a high school history teacher, I went into my Neville-Pribram Mid-Career Educator fellowship with a motivation to help my students better understand where popular history narratives come from so they can better predict where they are going. Look to the past to predict the future? Easy peasy, right?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/07/69/07699035-c19a-4151-9686-bcf99b761b3b/the_book_of_the_fair.jpg)

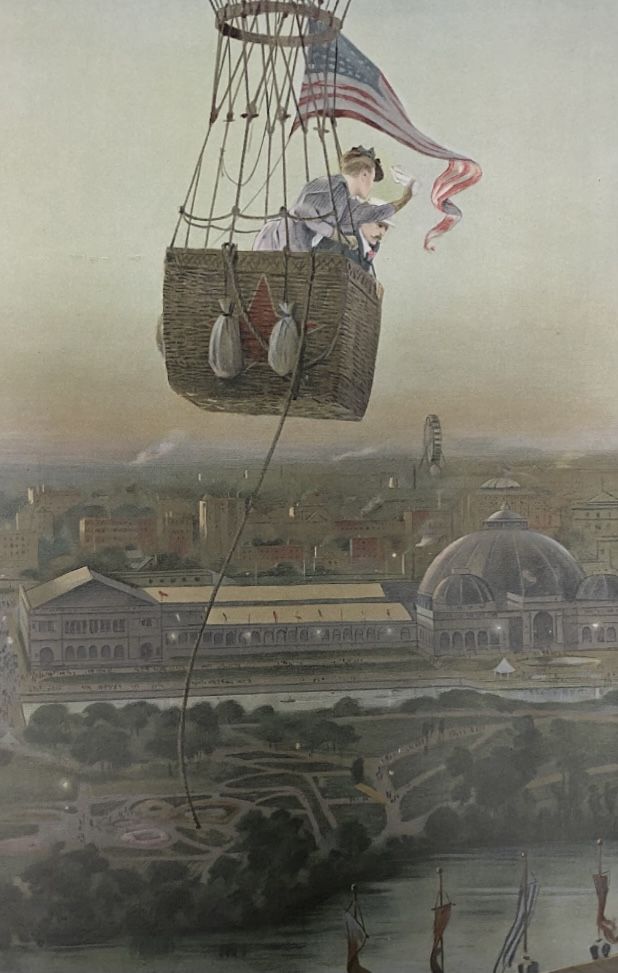

As a mostly world history and big history teacher studying at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library, I naturally flocked to the 1893 The Book of the Fair by Hubert Howe Bancroft. The Book was a popular recounting and survey of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, a non-critical celebration of American achievement. During my fellowship, I corresponded with a Bancroft authority, Dr. Travis Ross of Yale University, who I believe said it the best and I kept going back to his analogy with my students; the Book was analogous to a popular Netflix show as they were both “algorithmically perfected to maximize the market for an expensive work.”

I have been trained to teach in the discipline of Big History. French Historian Fernand Braudel believed that the most useful historical questions and analysis come from studying the “deep currents” of history; this translates to the study of ordinary people rather than just icons and focusing on transdisciplinary thinking as opposed to solely highlighting political and military history. A source such as The Book of the Fair allowed for a popular history that flipped geographic scales and meshed with a big history mindset. A big history pedagogical approach focuses on a cohesive cosmological, geological, and human narrative that goes so deep below the waves that they make Jacques Cousteau look like a vacationer snorkeling with his kids.

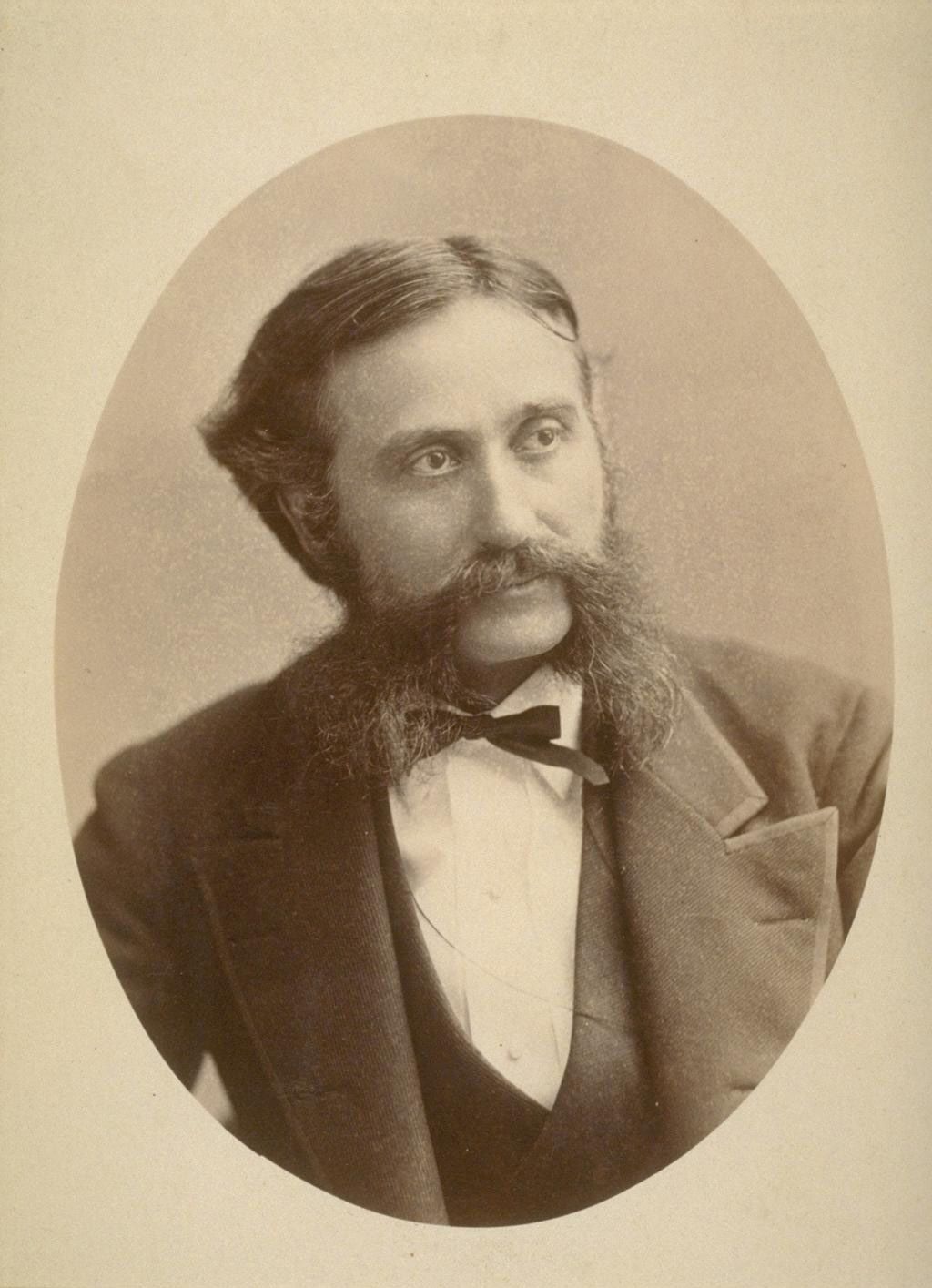

The 2019 fellowship at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library forced a timely self-interrogation for the impending ‘real history’ conversations. As anyone who has picked up a newspaper or turned on a TV in the past couple of years can tell you, the culture wars have come to history class. As a teacher, I have spent barbeques and holiday parties being asked by those on both sides of the aisle if I am teaching the ‘real history.’ I have been prepared for these fleeting moments on the axis of good conversation and self-actualization by staying out of the “waves.” It revealed that despite my global lens, I needed to zoom in and refocus. My American history lens was more of an implicit kaleidoscope– I had been stuck in the waves of American “Mythistory.” I had not yet gotten the memo about the revisionist thinking about the history of the American West. I had lived and taught in the Eastern Navajo Nation. I had spent time telling the Diné Code Talker’s story. Regardless, some of the old American West tropes remained hidden in my psyche, lodged somewhere between Clint Eastwood and ideas of pristine western wildernesses. Ironically, it took a figuratively global text written about the literal World’s Fair of 1893 to make this problem crystalize. For this academic adventure, we go below the waves to examine one man who told the story of the genesis of the American West. After I was encouraged to investigate the source of the Book, Hubert Howe Bancroft revealed our worthy problem. Bancroft achieved the unthinkable at the time by writing an affordable and all-encompassing history of the American West titled The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, but the dilemma lies in his integrated perspectives on race, gender, and class.

Anyone who has spent time with young people could probably tell you that the idea of a mid-nineteenth century mutton-chopped historian is not breaking into the TikTok top views. So how do I code this problem to appeal and engage young learners? Short Answer: “What is the California Dream?”

The Typical Classroom Conversations Around This Lesson:

“What does Bancroft have to do with the California Dream, Mr. Skomba?”

“Bancroft is known as the first to write a comprehensive history of California and the American West. He moved to San Francisco shortly after the Gold Rush and made his fortune in selling, writing, and publishing books. He lived his California Dream and established the mythistory of California for others seeking fortune and new opportunities. From the Gold Rush to YouTube influencers today, he incubated the mythistory of California…”

With the library’s resources at my fingertips, I graduated from The Book of the Fair to studying Bancroft’s magnum opus, the previously mentioned The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. The Works was notably criticized for Bancroft’s use of the ‘German Method’, the collection was highly debated because he tasked his subordinates with writing his historical volumes without credit or citation of the actual authors. In a twist of fate, he was even roasted by fellow historians for using this method at the 1893 World’s Fair.

Bancroft built his publishing empire and compiled the stories of the biggest names in the American West. He democratized endless volumes of knowledge, turning books into an empire, á la a Jeff Bezos of the 19th century, sans the rocketship, but sharing the inclination to wear a cowboy hat. Historian John Walton Caughey praised Bancroft when he stated “A prodigious historian he certainly was; generations hence he may loom up as the most significant figure that the West has produced.” Historian of modern California Kevin Starr equally praised Bancroft’s effort when he said “The fundamental genius of Hubert Howe Bancroft lies in the fact that he envisioned such a comprehensive history, assembled its materials, set researchers and writers to work, and produced, published, and marketed History with a Capital H he had emblazoned over the entrance of the History Building be built on Market Street”. Bancroft’s Works was an enormous feat and would be the students’ first introduction to Bancroft– it was our American West Nuremberg Chronicles. Our American West Wikipedia.

“So he did a good thing, Mr. Skomba?”

“He added to our collective understanding. A good thing indeed.”

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie so eloquently put it, there’s “danger in a single story.” Out of the volumes that have been confirmed as being authored by Bancroft, two of them deal with ‘Popular Tribunals.’ This is the second piece of the case study. Scholarship in the past decade by Dr. Lisa Arellano suggests that Bancroft uses the two volumes on Popular Tribunals to valorize what essentially equates to a lynch mob. Such executions are American schema via our spaghetti westerns. It was not until I interfaced with the scholarship that I could see the pattern of the tribunals. They were not Popular Tribunals but rather “Popular Lynch Mobs.” They preyed on non-white Californians and carried out outlaw executions with little to no factual evidence.

Furthermore, a third title that was also confirmed to have been written by Bancroft titled Literary Industries, includes derogatory comments on women in the literary industry:

“Several women were also employed upon these voyages. I know not why it is, but almost every attempt to employ female talent in connection with these industries has proved a signal failure. I have to-day nothing to show for thousands of dollars paid out for the futile attempts of female writers…If she have genius, let her stay at home, write from her effervescent brain, and sell the product to the highest bidder.”

Women, most notably Francis Fuller Victor (who is credited for writing the The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Oregon: Vol. II, 1848-1888) after Bancroft’s death) dictated, edited, and flatout wrote Bancroft’s Works.

“Can we trust his history, Mr. Skomba?”

“People are complex.”

Upon his death, Mr. Bancroft donated his library (the largest on the West Coast) to the University of California. The library at the University of California-Berkeley still bears his name. A copy of Mr. Bancroft’s correspondence with Andrew Carnegie can be found in the New York Public Library Brooke Russell Astor rare books reading room. He notes his agreement with Carnegie’s drive for philanthropy and endorses donating to worthy causes. His envoys to Mexico City or Europe were driven by his desire to build his repository of Western sources for posterity.

“So he was generous, Mr. Skomba?”

“Would you donate your life’s work?”

I originally wrote off the valorization of Popular Tribunals as a base intersection of dime novels and academia. History is not convenient–stereoscopic historical research shows us other secondary sources bring the race theory dilemma into focus. In Gilman M. Ostrander’s 1958 article titled ‘Turner and the German Germ Theory’ Ostrander quotes from Bancroft’s fourth and final self-authored volume of Works titled ‘Essays and Miscellany’ in order to compare him to the notorious Frontier Thesis presented by Fredrick Jackson Turner:

Unlike Turner’s essay, this earlier account by Bancroft was overtly, in fact jubilantly, race-conscious, as well as altogether carefree in its generalization… Both men were influenced alike by the intellectual currents of a day when Americans were possessed of boundless confidence in the race, the nation, the section and the individual, and when the inherent superiority of the Anglo-Saxon or the Germanic or the Teutonic or the Aryan race was a common intellectual assumption of the day.

“So he was a racist, Mr. Skomba?”

“He was a complicated historical figure worth studying. What did we learn in the process?”

With Bancroft, complexities abound. I believe that the most meaningful historical thinking happens in these messy edges of uncertainty and uncomfortableness. Discerning whether to deconstruct or assign value to historical narratives is a spiraling skill for both teachers and students. My intentions that drove this curriculum were never focused on making the students experts on H.H. Bancroft but rather equipping critical consumers of established history. I did not want or need my students to be experts on Bancroft’s biography. Instead, Bancroft’s case study gave us a worthy problem- a vehicle instead of a destination. I want them to test every claim they interact with, analyze context, and find out who wrote their textbooks. My time as a Neville-Pribram Fellow at Smithsonian Libraries (now Smithsonian Libraries and Archives) gave me the space and the energy to take off the practitioner hat to dive beneath the waves and spend time swimming in the deep currents. Doing such work might be as bumpy as the 19th century Wagon Trains, but once educators master the trail, they can help students predict what’s next.

The next great democratizer of information-the next H.H. Bancroft-just might be sitting in the second row of your classroom. I might have already taught her:

Further Reading:

Arellano, Lisa. Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Narratives of Community and Nation (2012).

Bancroft, Hubert Howe, The Book of the Fair (1893).

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. Literary Industries: Chasing a Vanishing West (2013).

Bancroft, Hubert Howe, The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft (1882).

Caughey, John Walton. “Hubert Howe Bancroft, Historian of Western America.” The American Historical Review 50, no. 3 (1945): 461–70.

Johnson, Rossiter. A history of the World’s Columbian exposition held in Chicago in 1893 (1897-1898).

McNeill, William H. “Mythistory, or Truth, Myth, History, and Historians“, The American Historical Review, Volume 91, Issue 1, February 1986, Pages 1–10.

Morgan, Lewis H. Review: [Untitled], The North American Review 122, no. 251 (1876): 265–308.

Ostrander, Gilman M. “Turner and the Germ Theory.” Agricultural History 32, no. 4 (1958): 258–61.